This conversation with Italy’s former prime minister Giuliano Amato is drawn from the e-book “Europe at a Crossroads after the Shock”, available for download here.

Nineteen years on, history is repeating itself, in new guises. December 2001: the West had just been tragically reunited by the attacks of September 11, but for months Europe had been pushed towards the great leap – that of genuine political unity – by something more: the perception of an historic opportunity, with the upcoming incorporation of twelve countries from the former Soviet bloc. The Union born in Maastricht could dare to take a gamble, even beyond the formal mandate of the Laeken Declaration, signed by the heads of state and government and carefully prepared in preceding months by Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstad, called for.

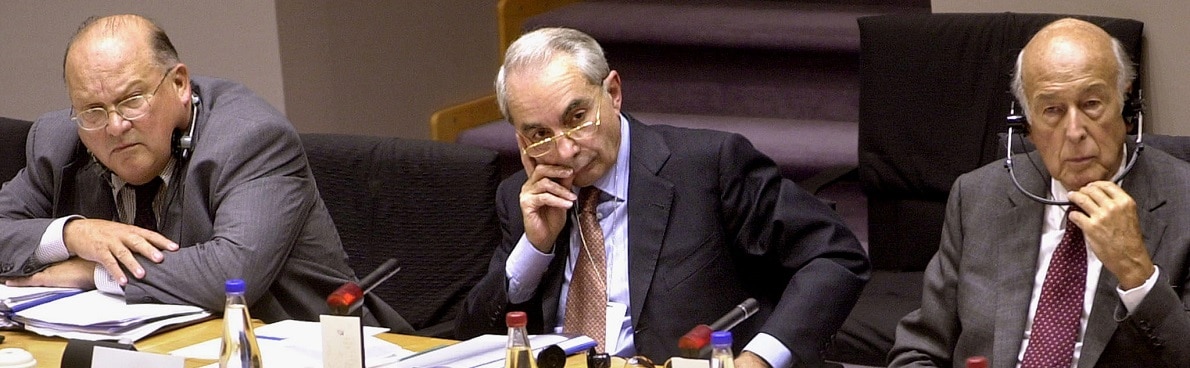

A “Convention on the Future of Europe”, led by the former French president Valery Giscard d’Estaing, who died on 2 December, and flanked by two prominent former heads of government – the Belgian Jean-Luc Dehaene and the Italian Giuliano Amato – was set up to realise those ambitions. It ended badly, as we know. The European Constitution conceived by that body – and carefully filtered through the political sieve of the governments – shattered against the wall of No votes in a deadly one-two from French and Dutch voters (May/June 2005) and the window of opportunity slammed shut for several long years.

A sea of problems and crises later, most recently the perfect storm of Covid-19, the EU is preparing – timidly, for now – to launch a new Conference on the Future of Europe. Leading it, at least in the wishes of the European Parliament, could be Verhofstad himself. Fifteen years after that bitter rejection, Amato, now vice-president of Italy’s Constitutional Court, recalls the political heritage left by Giscard, gathers his ideas on the lessons of that constituent season, and on the mistakes not to be repeated in the new one that might be opening up for Europe.

Mr. Amato, Valery Giscard d’Estaing passed away last December 2nd. Born in Koblenz in 1926, he had a meteoric rise in France, becoming President of the Republic from 1974 to 1981, held later a number of other posts, political and non, until he was appointed to head the European Convention between 2002 and 2003, with yourself at his side. What is his legacy as a man and as a politician?

He was a formidable personality. You only had to look into his eyes to see that there was an uncommon intelligence behind them. And not only in an intellectual sense. He had a way of looking at women that was absolutely captivating. Even in his 90s his exchanges of glances with the ladies were something to behold. He had been an enfant prodige of French politics. Much earlier than Macron’s generational breakthrough, he became De Gaulle’s finance minister at the age of 34 – clearly with the general’s favour, but also with an expertise that became legendary when he presented numbers, results and forecasts to the National Assembly without referring to a single written note. Prior to Macron, he was also the youngest head of state in the République, with the political confidence that allowed him to assume a leading role after clashing with Gaullism over his austerity positions on financial matters. He was elected to the Elysée even before the group he had created to relaunch himself actually became a party – a forerunner of Macron in this respect too.

And while in previous years he had essentially been the architect of domestic financial policy, it was as head of state that Giscard emerged as a European figure. With two essential outcomes that everyone remembers. First, the invention, together with others, but of which he was the protagonist, of the European Council, initially conceived as an informal forum for the heads of state and government to exchange views on the guidelines for European Community action, but which, thanks to its effectiveness, increasingly became the key body, even formally, in defining the Union’s strategic interests. Second, driven by his friendship and shared outlook with German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, in response to the global financial upheaval caused by Nixon’s breaking of the Bretton Woods agreements under an early “America first” as well as by the oil crisis, the creation of the cradle of the euro: the European Monetary System. This made it possible to peg European currencies to each other by means of a fluctuating band, with coordinated interventions by the central banks of the member states to guarantee it. It was an important invention which would in time lead “naturally” to the euro. Those who, like me, were faced in the following years as Treasury Minister and then as Prime Minister with the speculation of the markets, ready to attack one or another of the pegged currencies, looked in fact at the consolidation of that system into a single currency rather like today’s anti-Covid vaccine: the only way to prevent this disjointed pluralism of the market infecting a construction that tended towards unitary values. So Giscard gave a lot to Europe.

So much so that at the end of 2001 he was called upon to lead the Convention on the Future of Europe, which the governments had explicitly tasked with giving bodily and spiritual form to the integration project, with yourself and Jean-Luc Dehaene at his side. What was the atmosphere like during those months of work?

Everyone remembers the Laeken Declaration, but few recall an emblematic speech that the then German Green leader and Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer gave at the Humboldt in Berlin some months earlier, in May 2000. “The time has come”, he said. Europe has grown through integration projects, but we are facing secular challenges – was the essence of his speech, at the dawn of the new millennium – which urge us to abandon the logic of “step by step”: we need to make the leap to European federation, we need a European Constitution. That appeal did not arouse the enthusiasm of governments, but it nevertheless entered the larger debate of the European intelligentsia, because the time was right, and it created the expectation of “if not now when?”. It was from here that the request to design a real constitutional text entered the European Convention, not from the formal mandate given to it by the Laeken Council in 2001, whose essential demand was to consolidate the various prevailing treaties into one simplified treaty. Only in the last lines did it ask to consider for the future whether it might be useful to endow the Union with a Constitution. When the Convention opened, therefore, Fischer’s speech hovered in the air, as did the political figure of Giscard, who felt that his presidency would go down in history not for simplifying the Treaties but for giving Europe a Constitution. When Giscard announced this intention in front of the plenary of the Convention – made up, remember, of members of the European Parliament, national parliaments, governments and two representatives of the Commission – everyone stood and applauded. It felt like a true founding moment.

Then the wind changed direction.

We set to work to write a proper constitutional text from scratch, including sources of law, the division of powers, and citizens’ rights, as per the canons of a constitution. The primary work of the Convention was devoted to this part. However, that body did not have constituent power, but only the ability to make proposals to the Intergovernmental Conference and thus to the national parliaments. Well, in the final phase of the work, on the eve of the transfer of our work to the governments, something happened: the role of the government representatives grew in weight and political influence. I realised that something was changing when, to my question as to why a government representative had said “no” to some point, I increasingly frequently got the reply: “Because my government said no”. I dubbed it the sovereign niet.

The conflict became evident in a meeting that I will never forget and which, in retrospect, sealed the fate of that project. Once the work terminated, it was noted with the governments that the result was less than 130 articles of the European Constitution – the typical length of a constitution in Europe – plus over 300 articles that were the consolidated treaties. Aware that this would be subject to national ratifications, which in some countries would need to be done by popular referendum, Giscard and I said: let’s keep the two texts separate, let’s send them for ratification separately, otherwise the Constitution will drown inside the consolidation. Presenting a mass of over 400 articles as the European Constitution will provoke per se a reaction of rejection, we warned. The government representatives responded with disarmingly simple rigidity: it is difficult enough for us to get our parliaments to ratify one single document, and you want two?

We gave in. Months later, in the French referendum campaign, the supporters of the No vote held up two Constitutions, the national one – a slim little volume – and the European one. “You won’t even be able to read it all, and they want you to approve it! Say no”, they claimed. From my point of view, our mistake in the final construction was one of the main, though lesser-known, factors in the rejection and the demise of that Constitution.

Those who more or less sadly observed that demise have, however, made two fundamental criticisms: first, that the Convention over-reached the mandate that was given to it; second, that the Constitution was born from a top-down approach: the elites produce, the people receive.

There was some over-reach – of that I have not the slightest doubt – with respect to the sensitivity of the governments. If I were to try and deny this, I would be denying that 2+2 makes 4. I also know, having read a little history, that there are times when over-reaching has the power to legitimize itself. I do not believe that the absence of this strength in the idea of the European Constitution was due to a top-down approach. I see that as one of the most obvious but unfounded criticisms levelled at the process. You only have to look at the documentation of the work of the Convention to realise how broadly representatives of all democratic, economic and social bodies participated in it – dozens and dozens of meetings and discussions. If there is one accusation that is unjustified, it is that we shut ourselves up in an ivory tower from which we then handed down the Constitution. We did over-reach on some key issues because we had to see for ourselves that we were not able to break through the resistance of the governments, while the representatives of the national parliaments themselves sided more and more with MEPs in the work of the Convention rather than with their governments on various issues, demonstrating an unexpected advance in European sensitivity.

In this incredible 2020, we have seen the formerly inflexible German finance minister and now president of the Bundestag Wolfgang Schaüble himself speak of a Hamiltonian moment for the EU, and Germany open the door to a common European debt, and hence to a common taxation. At the time of the Convention, the EU was not ready for such a federal leap. And today?

Notwithstanding the prevailing pro-European spirit, we found that there was no willingness to surrender national prerogatives on economic and social policies. The working group on this issue was one of the last to be formed. And the results were a flattening of the existing situation. With colleagues from the socialist family – we met in the evenings to coordinate efforts – we recalled how the US ceased to be a confederation and became a federation not in Philadelphia, but when federal income tax was introduced a century later. This was how the federation acquired its resources, and Congress became more important than the state assemblies. But no one in the working group dared to take propose the idea of a European tax – or a common European debt. And that was one of the factors that convinced me that we were moving towards the creation not of a constitution but of a hybrid – half treaty, half constitution. So much so that the rule was retained that all national parliaments had to have a say on the Union’s financial resources. And that the Madison clause was rejected – there is no Hamilton without Madison – i.e. the possibility that the Constitution would come into force once a majority of the Member States had ratified it.

There is no doubt that recent years and the blows we have suffered – most recently Covid – are today leading to the notion that there can be a common European debt with which to finance common European expenditure. Schaüble is right: this is the time for federalisation. I have no illusions, however, because it comes at a moment when we can see how strong national identities are, much more so than those of the thirteen former colonies of the US. And how in Europe the mixture between advance towards federalisation and protection of national identity is destined to remain inextricable.

Which leads me to agree with the words of the German Constitutional Tribunal when it ruled on the Lisbon Treaty, which – let us not forget – took up our constitutional work. The Bundesverfassungsgericht stated clearly: this is and has remained a union of states, which has moments of integration and may have others; but shall they one day go as far as to entail the transformation of the Union into a federal state, that would need to be settled by changing not only European law, but also our national constitutions. I am convinced that this is the case, and that today’s Europe, where national identities are so strong, would be unlikely to accept a different solution.

Prof. Sergio Fabbrini points out in the e-book Europe at a Crossroads after the Shock that the apprehension about the federal leap that has moved the Nordic countries, led by the Netherlands, in recent negotiations, has more to do with a fear of small states being overwhelmed by big ones – a problem that also emerged, and was later resolved, at the time of American federalisation – than with the much vaunted North-South cleavage. How can this antagonism be smoothed out on Europe’s journey?

There is no shortage of legal expedients: one is the so-called proportional-regressive representation. Already used for the election of the European Parliament, it provides that the basic proportional principle regresses as the number of inhabitants of each country decreases – so that the weight of, say, a Luxembourg voter is about ten times that of a German voter. There remains the problem, which the EU-enthusiasts seem not to realize, of how to frame in this perspective the European referendum, which in the classic theoretical scheme should unitedly invest European citizenship with a constituent capacity for the future European federation. I have been working on this issue for about thirty years, and not one of the possible formulas of how that could work has been accepted, for the simple reason that the central principle of a referendum – one head one vote – creates an outnumbering, where the voters of small countries are outnumbered by those of large countries. And this is a crucial factor of democracy: the democratic nature of the system persists if and insofar as it represents each citizen, both as a European and as an Irish, Polish or Italian. This conundrum has always existed, but in an epoch of returning sovereignty concerns it has become even more important.

Postponed by the health crisis, in 2021 a new Conference on the Future of Europe will open involving once again the national governments and parliaments, as well as the EU institutions. Based on your experience with the Convention, what should this conference be, or avoid being, in order to succeed?

The biggest contribution can be made today if we succeed in building around the common debt a supranational system of economic and financial governance capable of sustaining the stability and development of the bloc, thus filling the gap that has existed since Maastricht, when we placed the single currency alongside a mere coordination of national economic and fiscal policies. The other asymmetry that needs to be corrected is the lack of a minimum social protection network at European level. Social policy is clearly a national prerogative, but just as we in Italy have invented “essential levels”, there could also be European ones. Thirdly and finally, I would recommend doing all this but not getting carried away by enthusiasm and trying to go too far. Because then a boomerang effect might threaten undoing even the things on which agreement had been reached.

Cover Photo: Then Vice-Presidents of the European Convention former Jean-Luc Dehaene (L), Giuliano Amato (C) and then President Valery Giscard d’Estaing (R) – Brussels, 03 October 2002 (B. Doppagne / BELGA / AFP).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).