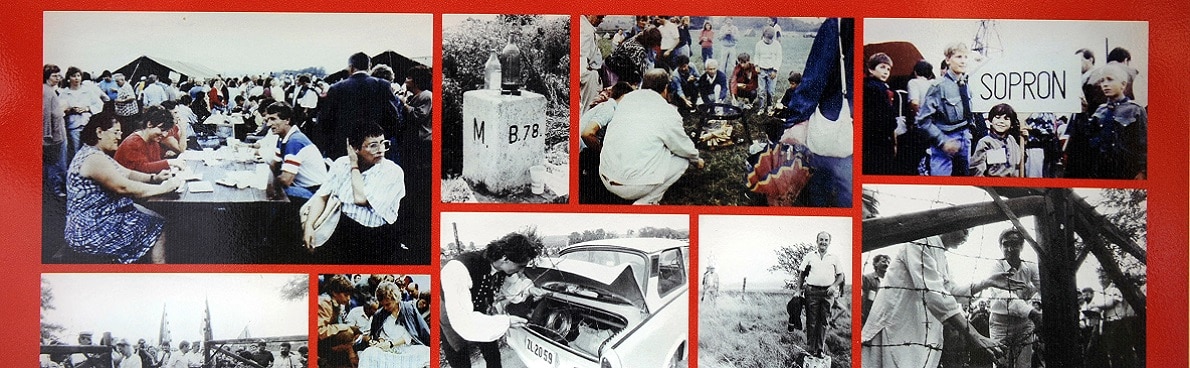

Even before Berlin, the Iron Curtain fell near the small Hungarian town of Sopron on the Austrian border. Before the breach at Bornholmer Strasse that signaled the end of the border crossings, the East-West frontier had already begun to weaken in Hungary. On the 19th of August 1989, just a few meters from the guarded and barb-wired checkpoint, members of civil society from both sides of the divide organized a picnic on a nearby lawn. A pan-European déjeuner sur l’herbe, a symbolic meeting aimed at ending the schism brought on by the Cold War. The initiative had been exceptionally permitted by the Communist government in Budapest and represented a small opening in overcoming the politics of division. That summer day however, thousands of people, particularly from East Germany passing through on their way to vacation in the Balkans happened to learn of the event and joined the gathering. They walked towards the historical separation line and without regard for their own safety decided to peacefully cross the border. Taken by surprise, the Communist regime’s police force did not react and refused to open fire on civilians. In April, just a few months earlier, the government had ordered for the electricity to be shut off along the 240-kilometer Austrian border. In June, Budapest could already feel the winds of change when the minister of foreign affairs removed a piece of the border. In November the wall would fall, heralding the beginning of Europe’s reunification and the construction of a common democratic area, which would welcome many of the former Soviet States.

“For many of us, 1989 represented a moment of hope. From then on Hungary changed, even though looking at its current policies, the scenario has really not evolved much” tell us artists Zsusza Brecz and Sarah Günthe. They are members of the group Pneuma Szöv, which literally means “Collective of Air”, which is headquartered in an old building in the center of Budapest. The collective brings together activists and visionaries that use creativity as a narrative instrument for opposition to the politics of prime minister Viktor Orban, leader of the radical right-wing party, Fidesz, in power since 2010 and winner of the last elections with over 50 percent of the votes. Established eleven years ago, Pneuma Szöv organizes street theatre and artistic productions as well as temporarily occupying public buildings with the aim of returning them to the community. The name of the group comes from its first exhibition held in the offices of an abandoned mall, where a series of actors recreated, as if in a laboratory, the smog that infests the capital, one of the most polluted cities in Europe.

“Through our work, we attempted to understand what remained of the legacy represented in the fall of the Berlin Wall. We reached the answer that 1989’s main promise was to reach Western living standards” add Berencz and Günthe. For four decades Hungary was a satellite of the Soviet Union and, as in other Eastern countries, the political upheaval brought on economic fantasies. Yet, the hope that Hungary’s living standards could improve and reach Western levels, and specifically those of nearby Austria, soon ran head long into the newly introduced market economy: mass firings and factory closures for those plants that were not considered to be in line with neoliberal standards. “From the Nineties onwards, unhindered privatization, rapid deindustrialization and the lack of social policy brought on the current authoritarian political stance and a lack of solidarity on all levels of society”, continue Berecz and Günthe. “As a collective, we retain that it is necessary to revisit alternatives that emerged at the end of the last Century and plan responses that do not erase our ‘socialist past’ in favor of a neoliberalist present. We believe that we need to write new paths, new routes that draw inspiration from our local history but, at the same time, are also international”.

Orban has dubbed his Hungary an “illiberal democracy”, referencing the theories developed by Fareed Zakaria in Foreign Affairs. He defines it as a State that does not refuse the principles of liberalism but also does not rely solely on its ideology. Orban’s populism has led to a wave of anti-immigration and authoritarian policies and the country is experiencing a period of growth; unemployment is going down and foreign investment has gone up. Though the economic policy may be producing positive results, cultural and democratic ecosystems seem to be missing. “The critical value of art is no longer appreciated, and we can only hope that something changes when this prime minister is gone. It has always been a problem, after 1989, to recognize the role of intellectuals and artists”, Pneuma Szöv explains. The function of knowledge as a surrogate for liberty was fundamental for real socialism, as was love for culture, music, and art for countries in the East. “In the Nineties there was more demand for art ‘in the western style’ and this pushed many to accept creative forms without thinking on one’s working conditions, which were not fully authentic”. “Budapest is no different. It is not easy finding public financing and often artists look for alternative funds through social enterprise, for example. Nonetheless, there are many that oppose the prime minister and there are many who claim that art is essential to imagine different ways of life and to create a sense of community”, add the activists.

Today, the prime minister’s executive is not confronting obstacles that put its survival at risk. Fidesz has a parliamentary majority with two-thirds of the seats due to its alliance with Christian-democratic party KNDP, it also benefits from wide-spread support in more rural areas of the country. It is a scenario that could indicate that the Hungarian people intend to prolong their support for strong-man policies that are faithful to its sovereignist and conservative electoral program. The European Union has reprimanded Orban on numerous occasions, accusing him of authoritarianism, of limiting freedom of communication and of a more general illiberal approach towards the public sphere. Many sustain that after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Hungary did not live through an authentic democratic process as it passed suddenly from a single-party system to a multi-party one, unprecedented in its history, a history that has been characterized by the absence of direct democracy.

The concept of democratia in Hungary seems to have become an expression of a single party’s agenda and that of one man’s politics. Fidesz was able to take advantage of the internal discontent towards the center-left while uniting the right and its supporters, tying them to a concept of functional participation in its political interests. General elections will not be held until 2022 but the ruling party has not fared well in local elections. Orban lost Budapest, where he garnered little support for his authoritarian movement. “His defeat was a significant shift. Hungarian citizens can now see a realistic alternative to the prime minister’s party”, affirm Berencz and Günthe. “Of course, how much this will be worth in the future depends on the capacity of the opposition. Nonetheless, we feel like we can breathe again”.

Photo: ATTILA KISBENEDEK / AFP

(A print showing photos from the Pan-European Picnic in 1989 is pictured as part of a permanent open-air exhibition at the Austrian-Hungarian border near Fertorakos)

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook and share our contents.

If you enjoy our analyses, videos and dossiers, stay in touch by signing up to our newsletter (twice a month).