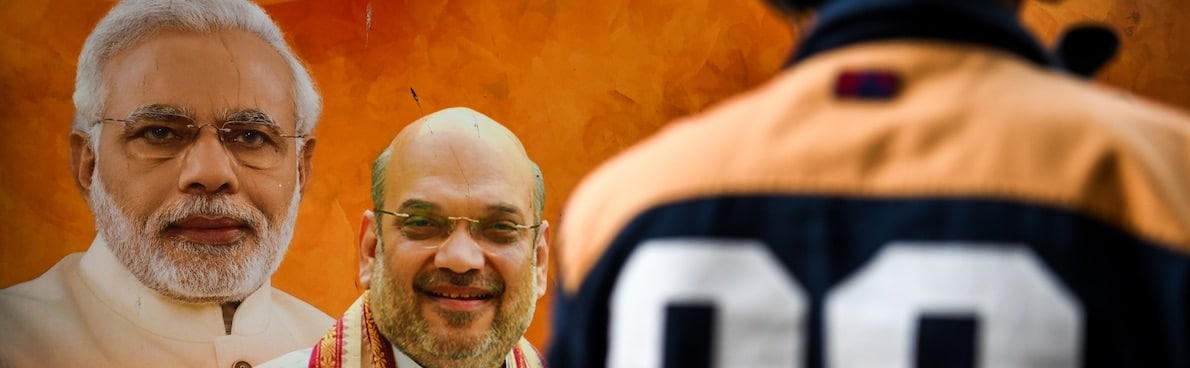

The president of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Amit Shah, while addressing a national executive meeting in New Delhi in September said that the party would continue to remain in power for the next 50 years if it won the 2019 general election. From ruling seven States in 2014, the party runs many States by itself or in an alliance. For a party that has earned such unprecedented electoral success, the feeling of invincibility is natural, but Mr. Shah’s claim sounds pompous.

In 1984, the Congress party won 404 Lok Sabha seats but tasted inglorious defeat in 1989. Likewise, its leader Indira Gandhi, who was venerated in 1971, had to bite the dust in 1977. India’s electoral world is dangerously precarious. Moreover, the Indian voter’s mind is very difficult to read. Looking at various political trends, however, the BJP’s dominance as single largest party for some time regardless of the outcome of the 2019 election is a fact.

The BJP’s dominance partly hinges on what sort of political resistance it faces from the Opposition. The clue that we get from the history of resistance is this: the most organised resistance to the BJP took place in 1996, when the party led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee was isolated and restricted to running the government for not more than 13 days even though he was seen to be more moderate than Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

A strategising

Such an event is not possible in 2019 or later for at least three reasons. First, having led the National Democratic Alliance coalition, the BJP has developed working relations with various regional parties who no longer see the national party as politically untouchable or are scared of its ideology.

Second, the leaders of regional parties, most often dynastic in nature, have very limited stakes in the national polity and a limited interest in fighting a battle outside their turf.

Third, the Narendra Modi-Amit Shah leadership, which presented itself as one with a difference in elections held 2014 onwards is also accommodative of their opponents. For instance, the Congress’s Rita Bahuguna in Uttar Pradesh or Himanta Biswa Sarma in Assam or the Janata Dal (United)’s Nitish Kumar were accommodated generously. So why is an ideological party so forgiving towards its opponents? Because its key objective is to drain the Opposition politics of vital resources so that any future consolidation against it is weak.

Anti-Congressism

Another crucial factor is the emergence of anti-Congressism as an ideology — a major source of political dissent and resistance in Indian politics that acquired concrete shape during the anti-Emergency movement in the mid-1970s. Political formations owing their origins to anti-Congressism are deeply sceptical of going with the Congress or its coalition as an alternative even if broadly they pretend to champion secular politics.

The ambivalence shown by parties led by the Biju Janata Dal leader Naveen Patnaik, Mr. Nitish Kumar, and the Telugu Desam Party leader N. Chandrababu Naidu (though he has now warmed up to the Congress) can be traced to this. On the other hand, this has led to some advantage for the BJP in seeking partners in the short and long term. Consequently, we are now witnessing the rhetoric of the Opposition leaders being more about anti-Modi-ism than anti-BJPism or anti-Hindutva as such.

Looking ahead

While the Modi-Shah leadership deserves credit for helping craft the electoral dominance of the BJP, the fact is that this team is not going to hold sway forever. On the other hand, political history shows that parties fragment for a variety of reasons such as ideological differences or a clash of personalities.

Take, for example, the Left or the Congress party, both of which experienced fragmentation. The Janata Party, in the 1970s, imploded though it was more a coalition of various formations. Thus, the BJP’s fragmentation is inevitable. What is hard to predict, however, is when this will happen. Given the almost symbiotic relationship between the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the BJP, some argue that the BJP would defy such a fate. But such an ideological grip could not stop B.S. Yeddyurappa, the former Karnataka Chief Minister, from abandoning the party to form the short-lived Karnataka Janata Paksha.

What must be highlighted is this: parties that had an umbilical link with the Congress party such as the Trinamool Congress or the Nationalist Congress Party have a secular thread in them. In the event that the BJP fragments, such parties could pursue an identical Hindutva line. The campaign and programmes of these parties could cause disruptions to minority and human rights.

The sharpening of these majoritarian tendencies would grow in both rhetoric and practice without bringing any change to the Constitution and the term secular remaining intact. Moreover, the BJP’s electoral dominance could contribute to the saffronisation of other parties, as they could emulate the BJP’s electoral strategies. This is evident in the workings of some of the non-Hindutva political parties. Such a development would also aggravate an already fragile secular polity.

Shaikh Mujibur Rehman teaches at Jamia Millia Central University, New Delhi. He is the editor of Rise of Saffron Power.

Published on The Hindu on 12/6/2018

Photo: CHANDAN KHANNA / AFP

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook. And share our contents.

If you liked our analysis, stories, videos, dossier, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).