This article was originally published on Society (Springer), 56, 203–209 (2019). We are thankful to both the journal and the authors for granting permission to reproduce it.

However counterintuitive it first appears, human rights are as much the problem as they are the solution to the contemporary challenge of constructing civil society. While such an argument will no doubt find great traction among certain extreme right-wing groups and politicians in Europe and the United States, we advance it here for serious, reasoned, and nonpartisan consideration. We are proposing an argument based on the seemingly inherent long-term social and political consequences of close to half a century of advocating human rights to the exclusion of other components of human good and fulfillment. The idea of human rights as the primary vehicle through which we articulate our shared moral vision— ignoring even such seemingly cognate ideas as constitutional rights or natural rights—has had (perhaps) inadvertent but nevertheless serious and deleterious effects world-wide and, we argue, has played an unappreciated role in the current rise of authoritarian, xenophobic, often racist and certainly antiliberal leaders and political parties in Europe, the United States, the Middle East, Russia, and elsewhere.

We are not arguing that human rights are a “bad” idea or that they should not be promulgated in the myriad international organizations, institutions, and fora where they hold sway. We are not questioning the legitimacy of the idea of human rights in a philosophical, political, or theological sense. Nor are we arguing, as others have, about the huge chasm between the rhetoric of human rights and its actual practice the world over; one need only to look at the case of refugees to see this. While one can empirically point to advances tied to human rights, more often than not this binds us as well to some of their less salutary, unintended consequences which can be destructive to the very communities they purport to protect.

The Politics of Rights and the Need for Belonging

In the past 50 years, the rhetoric of human rights has grown increasingly prevalent in political discourse, visions of international cooperation, and the legitimation of a liberal international order. It has also redefined the rhetoric and thought of the “left” in advanced capitalist countries. Arguments for working-class solidarity have increasingly given way to heated advocacy of individual rights and an “identity politics” predicated on multiculturalism and the need for “recognition”. In the European Union, for example, LGBTQ rights are mandated as part of EU candidacy and quite often the distribution of US development and humanitarian aid is linked to the receiving country’s support of “international standards” of human rights. The implication is that if the regime of human rights is enacted, European-style societies—assumed to the standard of civility and moral governance—will emerge.

A “politics of rights,” which were first advanced as an alternative to what many in the 1960’s saw as the threat of global communism—especially in view of the anti-colonial struggles of this era in Africa and elsewhere—succeeded beyond the wildest dreams of its advocates. The individual won out. Later, against the backdrop of the fall of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, and the rise of anti-democratic politics in many newly liberated African polities, the rhetoric (and concrete politics) of rights came to redefine what many thought of as “the liberal left” in the decades since 1989.

Liberalism had triumphed as a philosophical project and political agenda. At the time, however, the unintended consequences of this triumph were not even dimly perceived by its advocates and it continues to be ignored by far too many who unquestioningly accept the individual unit of human rights as a self-apparent virtue.

By making human rights the highest and most noble of our social and political virtues, liberalism has all too often denied, denigrated, or simply turned a blind eye to other, equally significant human needs and visions of the good. It is, for example, 70 years since Simone Weil wrote on the need for human belonging. In her words: “To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul. It is one of the hardest to define. A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future.”[1] We observe this to be an inescapable truth.

To be rooted is to belong and to belong is to be a member of a community, a community with its own past, its own traditions, stories, smells, tastes, jokes, obligations, recipes, holidays, moral judgments, boundaries of what is permissible and prohibited, basic frames of meanings, fears, and desires. That is to say—and it is increasingly necessary to say it in no uncertain terms—it is to be a member of a particular community, with a particular past, particular stories, smells, tastes, and so on. It is not for an individual to merely pick and choose belonging. Belonging requires others and communities are not easily fungible. The story of the Crucifixion and that of the Exodus from Egypt, or the slaying of Imam Hussein at Karbala are not interchangeable. Relations among Mennonites are not the same as those among (or between them and) Episcopalians. Attitudes of Jews toward Catholics are not comparable to those of Anglicans or Evangelicals. African American humor is different from Scottish humor and both again, from the jokes of China. Moreover, and critically, these communities are circumscribed entities. These, our communities of belonging, are not universal but are bounded, just as families are bounded; they have their own histories and their own trajectories, their own languages and jokes, their own obligations and taken-for-granted worlds, their own flavors and scents—their own understandings of home. They may be more or less open, more or less ascribed; their boundaries may be more or less permeable, but they do have boundaries which always define some “us” as against some “them”. And both us and them are group, not individual, categories; similarly with belonging contra rights.

Exclusion and the Need for Boundaries

If boundaries are to include in any meaningful sense, they must also exclude. The terms of inclusion and exclusion are, often enough, subject to (sometimes violent) negotiation, historical change, redefinition, interpretation, and endless contestation. But exclude they must, however difficult this may be for many to accept, especially in relation to the hegemonic framing of human rights as universal and transcendent of all (group) boundaries.

The simple logical truth—that we cannot have one without the other—is all too often ignored. Community among Jews, Christians, Muslims, and others for that matter, is a much-heralded virtue, bringing with it not only mutual concern, but mutual aid societies, hospitals, old-age homes, schools, charity organizations, burial societies, and much else. It is also, often enough, oppressive. Within certain communities, we may find an undo concern with what neighbors eat, how they dress, where they send their children to school, who they marry, and so on. Yes, to be sure, some communities are more restrictive than others—some define their boundaries in a more rigorous, ascriptive manner than others— but all are exclusive, as any group of people must be if it is to give full meaning to the terms of community. And it is precisely within these bounded communities—which are, moreover, real and active entities— that human actors are born, thrive, live, die, and make sense (or do not) of their worlds and the worlds of others. We cannot live without these communities and, despite all the dangers that arise from them, we submit that there is no possibility of human life or achievement outside of them. Again, this is not to say that “community” is an unalloyed good—it is not; often it is oppressive and restrictive—even if we discount its exclusionary character, which of course is the great bugbear of contemporary politics. But membership in community remains an essential component of any shared vision of the good.

This is the truth that Simone Weil pointed out during the raging years of World War II and to which Hannah Arendt also drew our attention, pointing out that not only are rights embedded within political communities, but that while we can indeed leave any particular community with its obligations and moral ties, such an act can also only replace one set of ties with another—for life outside community is not possible. These insights, however, are ones that our current liberal obsession with abstract, universal, and unencumbered human rights continually fails to recognize.

Identity Politics as Trope

Some may retort that the current and above-mentioned concern with “identity politics” is itself evidence of a general recognition of the importance of belonging and community among the denizens of the liberal order. To an extent this is true, but the very advance of the argument betrays its weakness. All of us, so we are told, “have” an identity or most probably, multiple identities; some even intersectional identities. But having an identity is possession, in a way similar to having a particular car, home, or even rights, for that matter. Having is not belonging. And having an identity is not the same as belonging to a community. People need to belong, not merely to have. Having (that is to say, different forms of ownership) is one way to organize the satisfaction of human material needs and having rights (sometimes) goes some way toward fulfilling the same function, but it is a far cry from the need to belong, to be born, grown old, die and be buried as a member of a community. And it is this, if anything, that appears universal.

A good friend of ours who took holy orders in Uganda quite some years ago, is continually affronted by the members of Pentecostal churches in East Africa who talk about “my Church”. For her, it approaches a desecration. The Church is not “mine”; rather, I am “of” the Church. Or, as another friend described in the Journal of Politics some years ago, “religion is not a preference.”[2] These communities then—those of which we are, rather than those which merely provide us with identities that we have—may usefully be termed communities of belonging.

This is an important distinction. Individuals may indeed claim particular identities (as they do particular rights) or have such identities (and rights) attributed to them. But this is very different from a sense of belonging. A refugee for example is an acquired identity often defined by struggle or plight, not by belonging. Syrian and Venezuelan refugees may have related experiences of displacement, but their reference for belonging will go back to very different “particular treasures of the past”. Making of the refugee status an “identity” thus becomes shorthand to describe a group without knowing it. (Interestingly, while rights are ascribed to individuals, it is often to a group—not to “known” individuals—that anger, resentment, hatred, and exclusion are directed.) Being a refugee is an experience that may be shared, and it may carry with it general characteristics, but rights ascribed to refugees are not stories of belonging. And often they do not even lead to belonging. They may be the minimal requirement for individual existence, but this is very different from membership in community.

Critical to community’s workings and role in sustaining human flourishing is the moral credit that is granted to their members. What we mean by moral credit is something colloquially phrased as affording someone the “benefit of the doubt.” As our moral knowledge, social obligations, and sense of what is right and proper—as well as improper and destructive—is held collectively by us as members of specific social groups rather than by us solely as individuals, an important part of what it is we know is bound up with who we trust. This is not an abstract notion but a bind in which we often find ourselves, called upon to grant moral credit to some source in matters which are, by their nature, almost always morally ambiguous. We may not dispute any particular “fact” or “set of facts”—the building of a mosque in lower Manhattan; the knifing of a marcher in a gay pride parade in Jerusalem; the murder of a Jew in Paris; the establishment of hidden cameras in the Muslim neighborhoods of Birmingham, England—but the frame of the act, the set of relevant external bits of information, and the histories needed to explain them will frequently be decided on the biases of our group belonging and the moral credit that we, as members of a group, grant to the source of such data.

One need only think of the 2016 stabbing of a Jewish man in Strasbourg, France by a mentally disturbed man shouting “Allahu akbar”. All bits of data may be factual, but it is often the biases of one’s group of belonging that determine which descriptive bits are explanatory—Jewish and/or mentally disturbed or Muslim. Description in itself is always commentary and never plain fact. The context that makes sense of an event is thus always particular as factual gaps are filled in by our community’s prejudices. In the United States, this is played out almost as parody in the different media outlets such as Fox News and the New York Times, that both weigh and contextualize information differently. And this is true on a much more granular level as well, within villages, towns, and cities the world over.

This is especially relevant for the argument we are making here, which is not about the divisiveness of party politics in the US or elsewhere, but about how the very basic frames of our knowledge are structured by the communities to which we belong. Belonging is not just an ineluctable emotional need; it is one of the very struts of our cognition and understanding, and as such of our ability to engage with the world. Abstract algorithms may be useful to the workings of Google or Facebook, but they are less than helpful in informing me about how to morally navigate the global refugee crises—due to the simple fact that it is not global, but a series of endless, particular crises spanning Africa, Asia, Europe, North and South America, and Oceania.

Strangers and the Rights that Make Them

While Biblical injunctions on treating “the stranger as yourself” would seem relevant in this context, the reality is somewhat different. Whether in decisions to prohibit refugee entry into Israel and therein maintain the “Jewishness” of the State of Israel (where 20 percent of the population are not Jews); or to “Keep Poland White”; or to return to “la vraie France”; or to an America prior to the passage of the Hart-Celler Act in 1965 (which put an end to decades of U.S. immigration policies that banned immigrants along racial lines for the purpose of maintaining a specific idea of white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant America), we are witnessing a wide-spread revival of exclusionary, xenophobic, self-referential politics and ways of life. Needless to add, this is the situation not only in Western and Eastern Europe and the United States, but in Turkey, Russia, China, and elsewhere. It is thus not an isolated, unique move but rather something emerging out of particular structures en force globally. Sadly—and to the deep chagrin of many—current politics in the United States, Poland, Germany, Italy, Russia, Israel, Turkey, Hungary, and elsewhere are evidence of the essential truth of Weil’s fundamental insight about the necessity of belonging—albeit as interpreted by right-wing, nationalist, and often authoritarian politicians and movements. What liberal elites refused to countenance, the global right has nailed to its masthead.

Given this well agreed upon state of affairs, it is strange and rather self-defeating for those who oppose these developments to respond by ever more stridently advocating those very policies whose political ascendancy has in fact led to the current situation. In most cases, the response of the liberal-left to what may politely be termed communitarian needs, calls for a greater sense of (national, regional, religious, etc.) belonging is a renewed insistence on human rights as the only morally legitimate arbitrator of social relations.

And this, as we are arguing here, is the problem. For it is precisely the abstract, general, and universal nature of the human rights argument that so many supporters of rightwing politics and movements take issue with. Rights provide no sense of belonging, appeal to no sentiment of shared community, and eschew the obligations entailed by already existing ties. To give a sense of what we mean, we quote the words of a local Boston ward politician, Martin Lomasny, which he related to Lincoln Steffens at the beginning of the 20th century. “I think”, said Lomasny, “that there’s got to be in every ward somebody that any bloke can come to – no matter what he’d done – and get help. Help, you understand; none of your law and justice but help”[3] (emphasis added). This is, in many ways, the heart of the matter. People crave the help and mutuality that comes with and within community, much more than simply the abstract and impersonal application of the principles of justice.

One could well argue that such claims can be made only when some minimal rule of law is already in place. And that may indeed be so. But it does not change the reality of people’s need for belonging, a need to live among those with whom help is not understood in terms of legalized assistance programs doled out by cold, bureaucratic, impersonal organizations and welfare agencies, but rather as arising out of a sense of personalized mutuality and a shared life. At the end of the day, what the Lomasny quote gets at is the huge chasm between enacting a regime of abstract human rights and life in a human community of mutual care and shared belonging.

That these communities are more and more being understood as walled enclaves— in the United States for Trump supporters; in Israel, Italy, Hungary; in many of the former Soviet bloc Eastern European states where the “iron curtain” built to keep citizens in, is being replaced with new, even higher razor-wired fences to keep immigrants and refugees out—is a matter of no small concern. But again, arguments for human rights do not properly address the problem; they exacerbate it.

The resulting situation is such where on the one hand, we have an idea of the public order as articulated by proponents of liberalism and of a politics of rights as: (1) secular, (2) predicated on the idea of the morally autonomous individual, and (3) oriented toward the preservation of different sets of individual rights rather than the realization of an idea of the Good. However, and at the same time, more and more communities in both the United States and Europe are made up of individuals who do not understand themselves to be morally autonomous, but rather see themselves as enacting different sets of God-given commandments (in the best of cases, and of racially charged imperatives in the worst of cases); and who have very clear ideas of a public Good that run counter to the legal recognition and assurance of individual rights. The result is the establishment of two competing arenas of social interaction, expectations, mutuality, “identity”, and commitment. One can be defined by what we would call communities of trust, the other by what we could term communities of confidence.

Demarcating Rights from Belonging

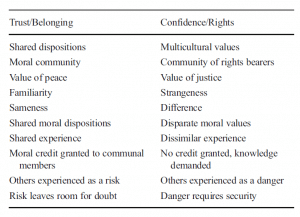

Communities of trust—analogous to what we called above communities of belonging—are those of shared moral dispositions, familiarity, sameness, and common experience in which moral credit is granted to community members in situations of risk, and the value of peace overrides that of abstract justice. In contrast, the realm of confidence refers to a collective of rights bearers, of dissimilar experience and disparate moral values in which justice is the highest virtue and others are experienced as potentially dangerous, requiring the enactment of security measures.

We can usefully schematize the two models as follows[4]:

Increasingly, in the contemporary world, communities of trust and belonging are markedly diverging from communities of confidence in values, principles of social organization, orientations toward the other, self-understandings, and fundamental terms of organizing collective experience. Increasing this divergence is becoming a divergence between truth and trust, reason and empathy, justice and mercy; that is, between the claims of a moral community articulated often (though not solely) by nationalist and authoritarian politicians and those of more abstract ideas of justice associated with the discourse of human rights. The right side of our chart—representing confidence, security, and abstract justice—is one of individual rights bearers, whose boundaries are sheer and absolute with but the thinnest of margins. The left side of our chart, on the other hand—defined by trust and moral credit, where peace (among members) is the supreme value—is to a large extent a social space comprising wide margins and thick boundaries, where a good deal of discomfort, occasioned by actions of others within the community, is “tolerated” precisely because individuals are seen as essentially part and parcel of one’s own ideas of self. Think here of a family, even an extended family, or members of one’s church, synagogue, temple, mosque, or even local gun club to get a sense of such broad boundaries that encompass both self and multiple others.

What we are seeing in the rise of right-wing movements and the politics of fear and xenophobia is the re-emergence of the claims of belonging within a world mostly defined this past half century in terms of rights-based claims. Let us be clear, we are not saying that all white supremacists, neo-Nazis, etc. are communities of trust. They are not. Some may see themselves as coming together around a moral community with shared dispositions, but they are also quite clear in excluding the objects of their anger on the grounds of rights. For them, it is precisely the other that does not have rights. And as we have already noted, while a need, community in and of itself is not an unbridled Good. The trust/confidence distinction shows how different relational approaches can be conceptualized, and how the roots of what we are discussing are more than semantics. Without understanding this dynamic, it is impossible to understand the contemporary political scene here or abroad.

Lest our argument come across as being partisan in pointing to the dangers of the right without drawing parity to the dangers of the left, the dangers as we see it are not binary but of different problems. The extreme right draws upon narratives of belonging to an exclusivist end which leaves a good deal of diverse societies at risk in ways that ease the naturalization of calls for the eradication of “less-desirables”. And this explains as much as anything the mass killings of Tutsis,

Bosniaks, Yazidis, and Rohingya over the last quarter century dominated by human rights rhetoric. The left is not about walled enclaves or ghettoization, but quite often it fails to grasp the importance of belonging—an insight the extreme right fully appreciates.

Toward a Politics of Difference

Sometimes benign but increasingly less so, the claims of community are challenging the liberal order of human rights in untold ways and with as yet unknown consequences. The challenge is how to accommodate these claims without necessarily accepting the demands that go with them—border

walls, indifference to the fate of refugees and migrants, forced assimilation of immigrant communities, racist and ethnocentric policies that support authoritarian rulers, etc. How can we articulate a politics of belonging—which we recall, always embraces some exclusionary element—without succumbing to the rhetoric of the extreme right both at home and abroad? While a continued advocacy of human rights may well be necessary, rights by themselves are a far from sufficient condition for human flourishing and satisfying the need for roots; a sense of belonging must be accommodated if we are to be spared a replay of some of the worst horrors of the last century.

While there are no easy solutions to this challenge, we suggest meeting it head on in the form of developing a new politics of difference. Eschewing both the hard and impenetrable boundaries being set up by nationalist politicians between “us” and any manner of “them”, as well as the ultimately homogenizing politics of abstract human rights that makes of every individual amorally autonomous agent devoid of inherited ties and obligations, we propose instead a rigorous engagement with communal differences. To do so, we must appreciate the implications of trust and confidence and reorient our approach to boundaries, neither seeking to do away with, privatize, nor absolutize them. We must come to see that boundaries do not only divide between an “us” and a “them”, but rather distinguish among “us” as we really are. Embracing difference as so many advocates of multiculturalism profess is most probably impossible; for most of us it is difficult enough to embrace our own traditions and pasts with their morally complex and compromised heritage. Living with difference is something else, however, and is indeed possible. But doing so necessitates the creation of new social and cognitive spaces, or better, places. Lest one think that this can be done digitally, it cannot.

Living with difference is not the same as controlling it. In 2018, Denmark began separating 1-year old children of immigrants “for at least 25 hours a week, not including nap time, for mandatory instruction in ‘Danish values,’ including the traditions of Christmas and Easter, and Danish language. Noncompliance could result in a stoppage of welfare payments”.[5] The aim is clearly not to create a place of difference, but, essentially, the forced assimilation of these children into Danish culture. It is not a “we” that is being built, but simply the numerical aggregation of already existing “Daneness”. The very idea of a “we” rests on differentiation, but here what is sought is not the coexistence of difference, but its erasure. This is not so different from Napoleon’s suggestion over 200 years ago to mandate every third Jewish marriage be to a non-Jew in order to fully assimilate the Jews in Europe.

In the United States, though certainly not there only, we find both assimilation as well as its opposite, the rather traditional way of managing otherness: segregation. The romanticized notion of the country as a “melting pot” of cultural diversity is a narrative that belies the reality of the American assimilation which has applied more to whites than nonwhites. Instead, there has been a long tradition of segregation, seen both in the struggle of racial and ethnic acceptance as well as the structural barriers that divide—from physical walls and ghettos to more bureaucratic means for deprivileging others through education, opportunity, and access to benefits reserved for the privileged. Segregation makes natural the distinctions of who belongs and who does not. While parochial slogans like “we are all Americans” imply sameness, the reality of American experience for many minorities is that being American has a subtext of whiteness (and its accompanying privilege) to which few Native American, African American, or Hispanic American can relate. Segregation in the United States has always existed alongside varying degrees of acceptance of racial and ethnic separation and can be found implicit in the enactment of pithy slogans like “Make America Great Again” that become rallying calls for exclusion, expulsion, and vilification.

We are arguing and advocating here for a very different approach: one that takes collective differences as not simply matters of individual preference but as constitutive of individuals and their communities; a resource to be preserved— however much discomfort may be involved for members of multiple “out-groups”—and a challenge to be met, rather than either ignored—through a discourse founded solely on rights—or erased—by advocates of nationalist and racist politics.

Rather than spaces of assimilation or segregation, places for difference must be constructed—in the military, in schools, workplaces, religious institutions, and yes, even in gun clubs where difference is encountered, wrestled with, and sometimes fought over. Only in this way can a shared language and thus a civil politics come to be.

Difference as a Path toward Civil Society

While human rights have become the dominant frame for an entire Western apparatus to think through civil society— concomitant a dramatic societal shift from trust to confidence rather than some balance therein—our argument to this point has been that it fails. We say this appreciative of what human rights has accomplished in improving the living conditions of many, but cognizant that it is insufficient precisely because its implicit prioritization of the individual is at the expense of belonging. And belonging is something that is necessary for existence beyond the individual; that is, for all existence that is social.

As noted earlier, the collapse of the Eastern Bloc led many to advocate an advancement of civil society predicated on the language of rights. The very collapse of communism throughout much of the world was taken as proof that a rights-based system was a structurally and morally superior way forward; an approach that would usher in peace, well-being, and democracy through a collective embrace of a Western liberal order. Yet almost three decades since the Fall of the Berlin Wall, many of those so certain in the success of the liberal order and the rightness of human rights, struggle to imagine a way forward other than to continue the course of persuading others to emulate them; to standardize the world in a more uniform and abstract way—a way that minimizes, even trivializes, difference for the sake of finding common ground; one predicated on relations of confidence.

As we have already claimed, however, not everything can be shared. Within religion, this is clear: efforts to build shared belonging upon the idea of the great monotheistic religions having Abraham as an ancestor in common falls apart when considering Jesus, who is seen as the son of God, a prophet, or a heretic. Such differences matter, for they are central to defining who belongs in one community over another. Human rights imply a universalizing language akin to “sharing Abraham in common”, i.e. part of the story, but not sufficient to define (or transcend) variations across communities. And if we are correct about belonging, then we must turn to other approaches for supporting its development. Approaches that recognize difference and the affective and structural distinctions brought about by relationships of trust as opposed to those of confidence.

For over 16 years, we have advocated and programmatically facilitated a way forward that enables members of disparate communities to recognize and accept their differences as they work toward a civil society.[6] In fortnightly programs with between 20 and 30 fellows from around the world, where difference was actively engaged—respected and struggled through—we have found it possible to build communities through shared experience without having to negotiate all that is held in common between group members. We have created environments, however temporary, where people can see the discomfort inherent to appreciating the differences that others bring—differences that we do not control and that challenge us; differences that at times even threaten who we see ourselves to be. It is only a small part of the solution but seeing the possibility of another way forward allows us to imagine enacting belonging in a world infatuated with rights. However briefly, whenever a community of difference comes together to do things together—not merely to assimilate, segregate, or exalt that which is shared—the possibility for moral credit to be extended to others becomes real.

In many ways, this is an educational endeavor—but not one of textbooks and classrooms alone, rather one that is experiential in nature. In practical terms, one need only to think back to childhood relations where playing at the schoolyard gave a sense of belonging together, not any ideological abstraction to which we as adults often find ourselves inclined. To engage those whom we do not know—and most often we do not know someone by the identity labels given to them— we must suspend prior judgment about what will come of our engaging together. Years away from the schoolyard of our youth, we may find ourselves very different from who our playmates have become, but we also find an opportunity for the benefit of the doubt to be extended on non-ideological grounds. Living with difference is not about giving up one’s deeply held (perhaps even moral) beliefs to live in community with another. It is about recognizing that some things cannot be shared, but also need not be resolved in order to share with others in community. Broadly implementing such an approach toward civil society involves taking belonging seriously, not only as something that emerges naturally but also as a quality that can be built through experience shared (made) with others. Development projects, educational missions, and political engagement would benefit from seeing difference as a resource rather than an obstacle. We are not suggesting that difference be praised in trivializing ways by pointing to the quaintness of cultural predilections. Living with difference is acknowledging the deep discomfort brought by very different and at times seemingly incompatible ways of being in community with others. It is, however, when we fetishize human rights at the exclusion of other human goods that we risk the loss of belonging. Human rights need not be the only mechanism for the extension of dignity. Dignity through the discomfort of difference is a way forward that allows belonging to exist without having to embrace the destructive and divisive rhetoric that seems to be on the rise.

Adam B. Seligman is Director of CEDAR—Communities Engaging with Difference and Religion and Professor of Religion at Boston University. Among other works, he is the coauthor of Living with Difference: How to Build Community in a Divided World (2015 University of California Press) which describes the CEDAR pedagogy.

David W. Montgomery is Director of Program Development for CEDAR and Associate Research Professor at the Center for International Development and Conflict Management at the University of Maryland. Among other works, he is the coauthor of Living with Difference: How to Build Community in a Divided World (2015 University of California Press) which describes the CEDAR pedagogy.

[1] SimoneWeil. 1952. The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind. Translated by Arthur Wills. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 43.

[2] Joshua Mitchell. 2007. Religion Is Not a Preference. Journal of Politics. 69(2): 351‐362.

[3] Lincoln Steffens. 1931. The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens. New York: Harcourt Brace. 618.

[4] We are fully aware of how much this categorization recalls the classical distinctions drawn by Tönnies between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. Our quibble is with the notion that one historically came to replace the other; we believe that both continue to exist concomitantly, that in fact in some sense one even produces the other.

[5] Barry, Ellen, and Martin Selsoe Sorensen. 2018. “In Denmark, Harsh New Laws for Immigrant ‘Ghettos’”. New York Times. July 1. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/01/world/europe/denmark-immigrant-ghettos.html

[6] Our work with CEDAR—Communities Engaging with Difference and Religion is described at length in Adam B. Seligman, Rahel R. Wasserfall, and David W. Montgomery. 2015. Living with Difference: How to Build Community in a Divided World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cover Photo: Louisa GOULIAMAKI / AFP

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook. And share our contents.

If you liked our analysis, stories, videos, dossier, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).