Despite the loss of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in three Hindi heartland States — Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh — there is little to cheer for India’s secularism. Looking at the campaign and manifestos of the two national parties, it is apparent that the campaign framework was generally defined more by competitive Hindutva [Hindu nationalism]. Let there be no illusion: the mere electoral defeat of the BJP does not mark the end of Hindutva as such, not even its retreat.

Given the hegemonic position that the BJP has established at present, even a defeat in 2019 could be only a transitory retreat. Given that the difference in vote share between the BJP and the Congress was so small in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, the BJP could easily return to power after the next Assembly elections with even mild anti-incumbency.

In the early 1980s, economist Pranab Bardhan described the Indian state as a patronage dispensing one, a formulation that remains valid even during India’s liberalisation post-1991. With the dimming of the Modi wave on the electoral landscape, though it took longer than expected, the 2019 parliamentary election will likely be party-driven and, more specifically, candidate-centric. Thus, a candidate of any party with a profile to offer better patronage could have a higher chance of succeeding at the hustings, implying greater decentralised use of money and muscle power.

Some of the buzzwords of the 2014 campaign — such as the Gujarat model, 56-inch chest, or even Congress-mukt Bharat — will not dominate 2019. Indeed, talk of the Gujarat model has receded from the campaign vocabulary of Prime Minister Narendra Modi for quite some time now.

Meaning of “Congress-mukt”

Unfortunately, serious academic research on the Congress party is rather limited and has been far less compared to what we have on the BJP or the Left parties, or even the Aam Aadmi Party. The deeply intertwined narrative of the Congress party with modern India has many complex layers. The fact that the Congress sometimes deviated sharply from its founding values was often felt by many of its stalwarts, both before and after the Gandhi family monopolised its leadership.

Without trivialising heroic contributions made by non-Congress leaders, it would be fair to say that many of the dissenting Congress leaders often played stellar roles in leading movements against the Congress governments, so much so that they literally helped set up almost all the non-Congress governments till 2014.

Consider the role of former Congress leaders such as Chandra Shekhar and Morarji Desai in 1977; V.P. Singh in 1989; I.K. Gujral and even P. Chidambaram from 1996 to 98; or Mamata Banerjee as part of the Vajpayee-led National Democratic Alliance in 1999. Regardless of our view on the Congress party, any dispassionate and objective study calls for critical scrutiny of the centrality of the Congress party’s role in the making and un-making of modern India.

But Mr. Modi’s clarion call to make India Congress-mukt, without doubt, has been ideologically inspired and can be traced to the Hindu Right’s ambition in the 1920s to build a Hindu Rashtra. To say that such a call by Mr. Modi is mainly inspired by the Gandhi family’s misrule would be a gross misreading of the ideological evolution of India’s political history.

Targeting minorities

On Muslim representation, the story is not particularly inspiring either. The BJP fielded only one Muslim candidate each in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, and both lost. The Congress fielded 15 in Rajasthan, out of whom seven won. In the Madhya Pradesh Assembly, there are only two Muslim MLAs.

Mob lynching is perhaps the most pernicious consequence of the growing aggression of Hindutva politics since 2014, and the pattern it has set poses the most mortal threat to India’s secular fabric. Yet, lynching barely figured as an issue of secularism during the campaign in the recent Assembly elections — although India’s first ‘Cow Minister’ in Rajasthan, Otaram Dewasi of the BJP, lost to an independent candidate.

The secular test

From Dadri in 2015 to Bulandshahr in 2018, a new trend has appeared, representing the changing face of violence against Muslims, in which victims are presented as perpetrators and the latter often enjoy the active state patronage. The end of state complicity in perpetuating violence and harassment against Muslims is the least that could be expected from the newly installed Congress regimes in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Those who wish to play the secular card in 2019 must recognise that they need to promise a lynch-free India to begin with.

Published on The Hindu on 1/5/2019

Shaikh Mujibur Rehman teaches at Jamia Millia Central University, New Delhi. He is the editor of Rise of Saffron Power.

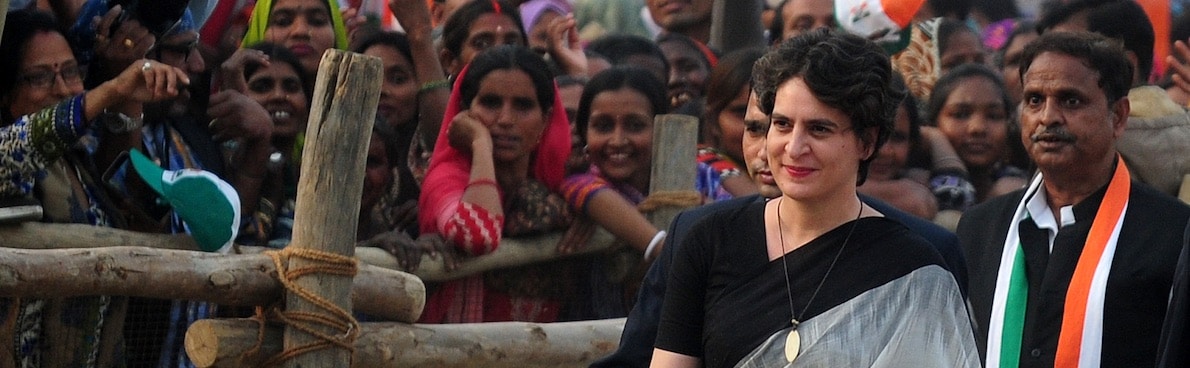

Photo: SANJAY KANOJIA / AFP

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook. And share our contents.

If you liked our analysis, stories, videos, dossier, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).