Just over a month ago, on August 5th, Prime Minister Narendra Modi participated in the Bhoomi Pujan, the foundational ceremony of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, the temple dedicated to lord Rama built upon the ancient Babri Mosque. Many observers wondered whether the temple’s first stone will also mark the grave of Indian secularism. The significance of this act goes way beyond today’s Indian political context, as India can be considered as a sort of laboratory for the most important political processes of modernity, from democratisation to inclusive citizenship to nation building. Unfortunately, Indian politics in recent years showcase a series of regressive trends shared by many democracies around the world, first of all the rise of right-wing authoritarian populism characterised by a manipulative and divisive use of religion. The Indian context thus provides a crucial observation point on how ethnocentric, right-wing populist movements appropriate religious symbols and vocabulary for their ‘nativist’ version of national community.

The last months have been extremely difficult. After more than one year of tension in Jammu and Kashmir, another major crisis erupted when in December 2019 the Parliament approved the Citizenship Amendment Act, affecting the Constitution’s article barring illegal immigrant from becoming Indian citizens. The amendment grants citizenship to those who, coming from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, belong to potentially persecuted religious groups identified with Christian, Buddhist, Sikhs or Hindu. The CAA reveals its anti-Muslim character when considered in conjunction with another legislative initiative, the National Citizens Record, a nation-wide census aiming at establishing who is a rightful Indian citizen. NCR requests residents for evidence of being legally in India since 1971; a requirement particularly hard to comply in many areas of rural India, where the access to public records is extremely difficult. The application of the NCR in Assam, where large amounts of immigrants from Bangladesh found refuge, has brought to the exclusion from citizenship of 1.9 million people. The two bills combined create a legal framework whereby those excluded from citizenship by the NCR could apply for asylum under CAA; an option that would not be available to Muslims. The tragic situation following the spread of COVID 19 has momentarily put a halt to the protests and the heated political confrontation on CAA and NCR, but not to communal tensions. Muslims have been accused by media close to the Government of “Covid Jihad”, i.e. of purposefully spreading the virus; these rumours have prompted a renewal of anti-Muslim violence.

Indian populism and Hindutva

A close friend and associate of Trump and Bolsonaro, Modi is a paradigmatic example of populist leadership. The populist stream in Indian politics, however, has deeper roots than the BJP. McGill’s political scientist Narendra Subramanian traces its origins all the way back to the anti-modernist discourse of Mahatma Gandhi (Subramanian 2007), as opposed to the democratic constitutionalism of other protagonists of the independence movements, primarily Nehru and Ambedkar. Christophe Jaffrelot and Louise Tillin (Jaffrelot and Tillin in Rovira Kaltwasser et al., 2017) also detect the presence of the populist mode at an early stage of Indian political life. In the decades immediately following Independence, Charan Singh incarnated an agrarian form of populism, opposing the “true India” of rural villages to the urban élites and political establishment; even more notable the populist turn brought about by Indira Gandhi. In the Seventies, Gandhi claimed to impersonate the essence of the Indian people, as in the slogan “Indira is India”, against the Party’s establishment, whilst at the same time undermining representative institutions and constitutional guarantees. Although Indira did not refrain from identifying herself with the goddess Durgha, the reference to religion was basically irrelevant in her populist rhetoric. The same can be said à propos the AAP (Aan Admi Party), the party probably closer to populism’s idealtype for its fiery anti-corruption rhetoric as well as for its refusal to identify with either right or left-wing politics. On the contrary, religious identity is absolutely central for the Bharatiya Janata Party, whose credo is hindutva. The identification indian-ness/hindu-ness was codified into a proper ideology in the 1920s, with the seminal book Hindutva: who is a Hindu by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (Savarkar 2008). Savarkar situated Hinduism at the crossroad of ethnicity, culture and history, and described Hindutva as a bond of Common blood (Jati), Love for the fatherland (Rashtra) and Common civilisation (Sanskriti). In this view, religious identity coincides with national, or even ethnic community: religious minorities, most of all Muslims, are labelled as alien from the genuine Indian/Hindu tradition. The BJP thrives off this monolithic definition of “Hinduism”, ignoring the rich diversity of traditions, and makes good use of it in the political project of constructing a majoritarian democracy. Needless to say, the unique approach to the nexus between religion and politics that goes under the name of “Indian secularism” is now in jeopardy.

India’s secular tradition in crisis

Secularism had already an important place in pre-independence debates, and became quite central during the drafting of the Constitution. In the Preamble, “We the people of India” solemnly resolved to establish a “sovereign democratic republic”. Neither Nehru or Ambedkar were in favour of including the attribute of “secular”, which was added, together with “socialist” only at the time of Emergency. In their mind, the Constitution’s defence of freedom of religion (articles 25-28) was sufficient, and a specific mention of secularism was not appropriate for the Indian context.

In fact, Nehru’s project was the construction of a nation of citizens defined by their Indian-ness rather than by their “communal” identities; citizenship was to bear a promise of liberty, equality and justice. In spite of all its shortcomings this vision of “inclusive nationalism” made it possible for a distinctive form of secularism to emerge, quite different from the Western notions of separation between religion and politics and State’s “neutrality” (Bilgrami 2017, p. 698- 709) and better captured by Rajeev Barghava’s definition of “principled distance” (Barghava 2013). This legacy is now under attack, by the BJP and more in general by the whole family of Hindu right-wing organisations gathered under the umbrella of Sangh Parivar. Recently, the flag of secularism has been the target of a re-appropriation attempt by the BJP, as the Nehruvian heritage is branded as “pseudo-secularism” and blamed for being inclined to “pampering” religious minorities.

The response of civil society

Since the CAA bill was approved, civil society has mobilised all over India. The Protest started in Assam and gradually spread to all the Northeast to reach the whole country. The month of December 2019 saw major protests in Delhi, at J. Nehru University as well as Jamia Millia Islamia, immediately followed by violent reactions by the police; particularly brutal was the police attack on JNU on January 10. Among the many civil society actions all over the country the sit-in that for 101 days blocked the area of Shaheen Bagh in South Delhi is especially significant for the mode and content of the protest. Began as a road blockade by a small group of Muslim women, the protest grew to involve thousands of other women mostly, although not exclusively, Muslim, who stood their ground, day after day without any interruption for almost four months.

The women of Shaheen Bagh soon became the fulcrum of the anti CAA movement: a sort of “camp” flourished around the sit-it, where all kind of organisations gathered, mobilising in different forms, from political debates to street art and interfaith prayers. A glance to the multicoloured, peaceful crowd would immediately reveal the political significance of the protest. Ambedkar’s portraits floating over the crowd in banners and placards, the thousands of tricolored balloons, the national flag painted on young women’s cheeks, the national anthem, the slogans (a placard held by a young woman read “my religion is Indian-ness”): all these signs embodied a genuine intersectionality between political, religious and gender identity in view of active citizenship. The women mobilised as Muslims as well as citizens, or, more importantly, as citizens defending universal rights because of their religious identity. At the same time, they denied the representation of Muslim women as victims of the patriarchalism of their religion, typical of BJP propaganda. Shaheen Bagh was a protest of civil society, in the name of the Constitution and the values it expressed; in the words of Neera Chandhoke, “they practice what has been called by scholars performative citizenship, wresting popular sovereignty from the tight-fists of power holders, reclaiming rights, asserting rights, and declaring in Hannah Arendt’s words, the right to assert rights” (Chandhoke 2020).

Police violence did not put an end to Shaeen Bagh – Covid 19 did. The situation in the first months of 2020 has for obvious reasons worsened. Approximately 46 million people have been expelled by the great metropolitan areas and are now on the move; meanwhile, religious and political conflicts remain unsolved. This is evidently a dramatic moment not only for India’s secularism, but for its democracy tout court. Hopefully, what we are witnessing today is a “crisis” in the original sense of the term, that is a moment of judgement. Rajeev Bhargava has observed that Indian secularism is not dead; yet it needs to transform itself so as to identify “new forms of socio-religious reciprocity […] and novel ways of reducing the political alienation of citizens, a democratic deficit whose ramifications go beyond the ambit of secularism” (Bhargava 2020). Shaheen Bagh, and the thousands of other protests all over India in the name of citizenship, inclusion, and pluralism give reasons to hope that this crisis will mean a renewal, and not the end by asphyxiation, of democracy and pluralism in India.

Bibliographical references

Bhargava, Reimagining Secularism Respect, Domination and Principled Distance «Economic and Political Weekly » Vol. 48, Issue No. 50, 14 Dec, 2013

Bhargava, The future of Indian secularism, «The Hindu», August 12 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/the-future-of-indian-secularism/article32329223.ece

Bilgrami, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohandas Gandhi, and the Contexts of Indian Secularism in J. Ganeri (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Indian Philosophy, OUP, 2017, pp. 693-716

Chandhoke, The strength of civil society is its spontaneity, collective mobilisation, https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/indias-civil-society-moment-citizenship-act-npr-nrc-6243207/ 2020

Jaffrelot and L. Tillin, Populism in Indiain C. Rovira Kaltwasser, P.Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism OUP, 2017,179-194

V.D. Savarkar, Hindutva: Who is an Hindu?, Hindi Satidya Sadan, New Delhi 2003

Subramanian, Populism in India, «SAIS Review of International Affairs» Johns Hopkins University Press, Volume 27, Number 1, Winter-Spring 2007 pp. 81-91

Debora Spini teaches at New York University in Florence and Syracuse University in Florence. Her research interests focus on religion and politics, with a special interest on Protestant theology, secularisation/post secularisation, as well as the role of religion in violent conflicts. Recently, her research extended to the manipulation of religion by right-wing populist movements and parties.

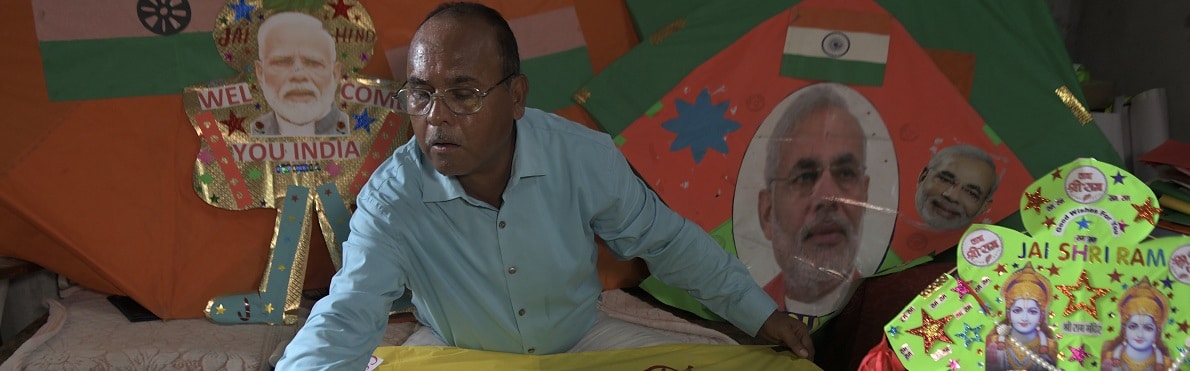

Cover Photo: Narinder Nanu / AFP

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to share and interact with our contents.

If you like our stories, videos and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).