In 1948 there were 260,000 Jews[1] living in Morocco, forming the largest Jewish community in any Arab-Muslim country. However, in just two decades these figures were to be totally upended due to a serious human, cultural and religious haemorrhage that deprived Morocco of its Jewish dimension and consequently of the opportunity of being an extremely valuable cultural melting pot.

The presence of Jews in Morocco has been linked to historical movements in the Mediterranean basin for thousands of years. In Volubilis, near Fez, archaeological digs have proved the existence of various Amazigh tribes of Jewish faith that can be dated to two thousand years ago (2nd Century BCE). This autochthonous nucleus, the Imazighen Udayen (meaning “the Amazigh of Jewish faith” in the Amazigh language), were probably Judaized following contact with the Carthaginians and the Phoenicians, and during the Roman, Byzantine, and Visigoth eras were joined by many other groups of Jews; these included the Toshavim, who generally fled the persecution and intolerance of the early centuries of the Christian era and during the European Middle Ages.

With the arrival of the Muslims in 682 CE, Jewish migration towards Morocco did not slow down, with various Jewish communities continuing to arrive from places such as Salonica, Constantinople, Egypt, and the Iberian Peninsula. Muslim laws and above all the Dhimma contract[2], which acknowledged the people’s right to freedom of worship and protection after paying an individual tax known as jizya, favoured the flourishing of Jewish culture, equipping it with an additional spoken and written language: Arabic. And it is certainly for this reason that hundreds of thousands of Muslim and Jewish refugees, who had been expelled from Andalusia by Isabella of Spain between 1460 and 1492, chose the coasts and cities of Morocco as their new homeland.

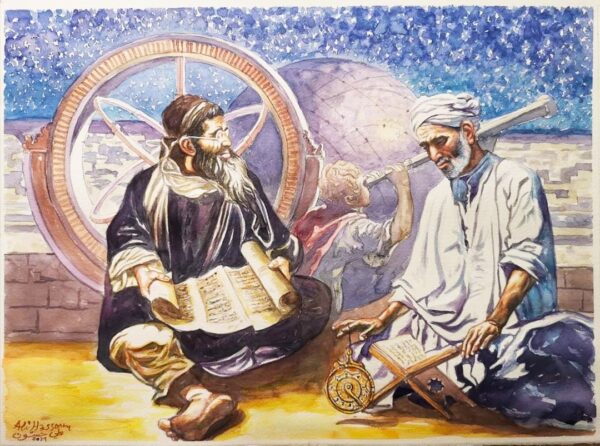

With the arrival of the Mogorashim (the Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal) Morocco’s Jewish community increased. This historical period, characterised by the merging of Jewish-Andalusian culture with the Jewish Maghrebi one, within the context of a moderate Moroccan Islam impregnated with the teachings of the sufi school, was one of the golden eras of Moroccan civilisation. Its fruits which continued to blossom, encouraging peaceful and fruitful coexistence between Jews and Muslims, were put at risk only by the French and Spanish colonisations.

The beginning of the end

While still flourishing, in 1948 the Moroccan Jewish community was in fact entering its final days. The upheaval took place over the course of just a few years, and can be attributed to the following historical events:

–> French and Spanish colonisation. With the aim of weakening Morocco’s national unity, the two mandating powers applied selective policies to favour the assimilation of Jews and cultivated their difference from the rest of the Muslim population. This created a certain degree of tension and mistrust towards Moroccans of Jewish faith, who often appeared to be conspiring with the occupiers. Although Moroccan Jews were not given French nationality (their Algerian co-religionists were naturalised French with an 1870 decree also known as the Cremieux Law) they nevertheless enjoyed favourable treatment from the French and Spanish protectorate, especially as far as education, access to public services and the administration were concerned. These were privileges that Muslims were often deprived of;

–> The birth of the State of Israel (1948) and its leadership’s appeal for Aliyah (a return – literally “ascent” – to the Promised Land);

–> The zealous activism of the Jewish Agency in Moroccan territory. This Zionist organisation, at the time led by David Ben Gurion, had in 1952 set up a transit camp in Mazagan (present-day El Jadida) and in 1955 it created a secret network whose mission it was to organise the migration of Jews to Israel (le réseau Misgueret);

–> Morocco’s independence, basically supported by a nationalist ideology with powerful Islamic references[3];

–> The subsequent wars between the State of Israel and Arab countries (1948, 1967, and 1973.) The birth of the State of Israel and consequent loss of Arab territories and the beginning of the Palestinian nakba, were experienced throughout the Arab world as a catastrophe, a disgrace. Popular feelings among Moroccan Muslims were supportive of the Arab people and armies defeated by Israel in 1948 and 1967. It was perhaps also because of this that the Moroccan Army was part of the united Arab forces that declared war on Israel in 1973. Moroccan troops had been deployed to the Golan Heights and fought in various battles against the Tsahal. All this created a distance between Jews and Muslims in Morocco. On the one hand there was no longer a difference between a Jew and an Israeli as far as Muslims were concerned, while on the other hand the Jews effectively felt they were at least sentimentally tied to Israel because various communities of Moroccan Jews, hence relatives, had in the meantime migrated to Israel. The atmosphere at the time made the Jews feel insecure as well as personae non grata. It must also be noted that among Moroccan Jews there were some who approved of and supported the Palestinian cause, such as Abraham Sarfati and Marcel Cohen.

–> Finally, the complicity of the Moroccan authorities who, out of gratitude or opportunism towards the State of Israel, silently accepted the exodus of Moroccan Jews. The day after independence, the monarchy found itself threatened by both the Moroccan nationalist movement that wished to restrict its power and by foreign states and leaders (Nasser, Ghaddafi, and Boumédiène) who in the name of revolutionary pan-Arabism plotted against the Moroccan monarchy. It is to this period that the first instances of cooperation between the monarchy and the State of Israel date back. Furthermore, the Interior Ministry, led by the then trusted General Oufkir, billed the Jewish Agency US $50 for every Jew that left the country. Although this involved an impressive mobilisation of resources and an enormous movement of people, the Makhzen (word used to indicate the Moroccan State’s coercive power) had managed to allow it all to take place in silence[4].

In addition to these complex historical reasons, one must not neglect individual and religious aspects. Many Moroccan Jews saw the birth of the State of Israel as the fulfilment of a Talmudic prophecy, in the mystical sense of the word. Aliyah towards Eretz Israel was perceived by the Jewish masses at the time as a religious duty and a longed for spiritual call. The dream of ethnic and religious Jewish unity was too tempting for a community that practiced a genuine and primitive religiosity (as did the Muslims), little contaminated by the events and evolutions that European Judaism had undergone above all with the birth of Zionism.

Multiple identities

Between 1949 and 1967, 200,000 Moroccan Jews left Morocco this way, with another 50,000 following between the 1970s and 80s. Of these, 90 percent emigrated to Israel while the remaining 10 percent spread between France, Spain, Canada, the United States, and Latin America. Now, only 3,000 Moroccan Jews remain in Morocco.

The Moroccan historian Haim Zafarani allows us to penetrate the life and traditions of this community, “marked by a sort of bipolarity: on the one hand it expresses a belonging and an attachment bound to its country (Morocco), while on the other it cultivates extremely close bonds with Jewish universal ideas through the Bible, the Talmud, and the Halakhà”[5]. He also states that “between Jews and Muslims there was active solidarity in the intimacy of language and in the analogy of mental organisation as well as a not indifferent amount of symbiosis or even religious syncretism expressed both in everyday life and in life’s most important moments.”

Having been rooted in the territory for millennia, Jews, on the other hand just like Muslims, were by no means a monolithic and homogenous element, far from it. “In Morocco – says the historian Daniel Rivet – there were a number of Jews and not a single abstract Jewish community. There was a profound distance between a small Jewish craftsman in Debdou and an important merchant in Tangiers doing business with the Sultan and sharing interests and relations with the international Jewish circles consisting of important professionals and businessmen. These are differences and even contrapositions found at a cultural level. On the one hand there were old rabbis that held the reins of a community not influenced by the Haskalà (Jewish Enlightenment.) On the other, there were the alliancistes, the progressives who had graduated from the schools of the Alliance israélite universelle [6]. Without forgetting, one must add, the differences between the Amazigh and the Arab-speaking Jews, the Jews in the mountains and those living on the coast, the Jews of Fez and those of Casablanca.

Two thousand years of shared history, shared geography, relations, language, and a common destiny, ensured that Jews and Muslims developed a common and shared legacy.

Traces on the territory

It is often said that Morocco is a holy land for the Jews, and this is true when one considers the high concentration of Jewish places of worship; synagogues, Jewish cemeteries and sanctuaries spread all over the country – from Tangiers in the extreme north all the way to Tafilalt in the desert, from Oujda in the East to Mogador on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. There were even some places in the interior of the Atlas Mountains that had a Jewish majority until 50 years ago (Sefrou, Debdou).

In the 1970s, when King Hassan II acted as mediator during negotiations between Israel and Egypt that ended with the 1979 Camp David Accords, with only a few thousand Jews still living in the country, Morocco enacted policies of rapprochement with the Moroccan Jewish diaspora. During those years those who had left were allowed to return to Morocco to visit their places of worship. This religious tourism has never stopped and nowadays there are still thousands of Moroccan Jews from Israel and from all over the world who gather for the Hilulate or Zyarat[7] in the various sanctuaries of Jewish Tsadikim (righteous men). There are more than 700 Righteous Jews who lived and are buried in Morocco. Nowadays, Hilula attended by Israeli pilgrims include those of Rabbi Yahya Lakhdar near the city of El Jadida, of Rabbi David Ben Baroukh Azogh in Taroudant, and of Rabbi Aman Bendiouan in Ouzzane in northern Morocco. And on religious syncretism mentioned by Haim Zafarani one must, for example, remember that several Tzadikim are venerated by both Jews and Muslims.

Tradition and nostalgia

The silent exodus of the Jews from Morocco conceals a rift too painful both at an individual and communitarian level for Jews and Muslims alike. In the mellah (Jewish ghettos) of Fes, Marrakesh, Essaouira, Meknes, or Rabat, the Star of David still remains visible, engraved on the doors of homes or on the shutters of shops once occupied by Moroccan Jews.

These feelings of loss and mourning are well expressed in the literature and music of Moroccan Jews. The novelist and militant Edmon Amran El Maleh was one of the best authors to have narrated the vicissitudes of Jews in Morocco (Mille ans, un jour; Fenec 1990). The same can be said about authors such as Marcel Benabbou, Joseph Shtrit, Sami Berdugo or Nicole Elgriss; while singers Pinhas Cohen, Sami El Maghribi or Raimonda El Bidaouia remain better known as performers of Moroccan Jewish music and raconteurs of the destiny of a community obliged to live in exile.

There are traces of two thousand years of history during which Morocco’s Jewish community expressed immeasurable vitality, contributing to Morocco’s political, economic, cultural, and scientific life. In addition to the abovementioned Jewish personalities who enriched the country’s history, one must also mention others; some of whom are still active today, such as André Azoulay, economic advisor to King Mohamed VI, the diplomat and former Tourism Minister Serge Berdugo, the founder of “Transparency Maroc” Sideon Assidon, the artist Deborah Benzakine or the singer Haim Botboli. There are others who have left Morocco, however reiterating on many occasions their bond with their origins as is the case with Israeli politician David Levy, the French actor Gad El Maleh or the French physicist Serge Harouche (2012 Nobel Prize for Physics).

Moroccan Judaism nowadays

Jews currently living in Morocco are citizens with equal rights and duties compared to their Muslim compatriots. Freedom of worship and the possibility of resorting to Rabbinic courts to solve their controversies is a fully acknowledged right. In fact, Morocco remains the only Arab-Muslim country in which Jewish religious functions are still celebrated in synagogues (Yoshayaho Pinto is Morocco’s Grand Rabbi), while the judicial system includes rabbinic courts that are still employed today.

A few years ago, the Moroccan authorities, under the aegis of the King himself, inaugurated large sites for the restoration of all places of interest for Jewish culture. These initiatives also concern education with the introduction of the history of the Jews in Morocco in books used in state schools, while the Museum of Moroccan Judaism opened in Casablanca in 1997.

I knew about the nostalgia felt by Moroccan Jews for their origins; I had read various books on this subject, seen films and documentaries[8], but it was a chance encounter with an Israeli tourist of Moroccan origin a few years ago in the Egyptian part of the Sinai that truly taught me the intensity of that bond. Massoud, who was born in Israel to parents born in Israel, and who had never set foot in Morocco, nonetheless spoke the Moroccan dialect passed down to him from his grandmother, and like most Israelis of Moroccan origin he lived within in a microcosm that had cloned the life that they had once had in Morocco and transplanted it to Israel. In the cities of Tel Aviv, Ashdod, or Natanya, the cuisine, the parties, the street names, the music, the traditions and customs have remained almost intact, packed up from Morocco and moved to the heart of Israel. With Massoud, as so often happens when two compatriots meet abroad, we found many subjects to discuss. The customs of our shared Moroccan culture protected us from the aggravation of broaching subjects that would divide us.

The researcher Emanuela Trevisan Semi commented on the Moroccanisation of Israeli space, saying “When, in 1992, King Hassan II said that few countries could boast 750,0000 children acting as ambassadors in Israel, this was not just rhetoric. He was instead alluding to an already ongoing process; the introduction of Moroccan locations, objects, stories and times into Israel”[9]

Another revered Moroccan who has rightfully entered the Israeli fabric and in particular the Yad Vashem museum, is the late King Mohamed V (grandfather of the current ruler, Mohamed VI), considered Righteous Among the Nations for his decisive role in protecting Moroccan Jews from persecution during the Vichy regime. Mohamed V refused all segregation or deportation of Moroccan Jewish people by the Gestapo declaring that “There are no Jews and Muslims in Morocco, there are only Moroccans.”

Notes

[1] Emanuela Trevisan Semi et Hanane Sekkat Hatimi, Mémoire et représentations des juifs au Maroc, Paris, Publisud, 2011

[2] As regards to the Dhimmi, the historian Haim Zafarani states that, “The condition of a Dhimmi was certainly degrading and often precarious, but generally speaking it was a liberal juridical charter, which allowed an extremely high level of judicial, administrative and cultural autonomy compared to the arbitrary conditions in which Ashkenazi Jews lived under Christian rule.” – Haim Zaafarani, Deux mille ans de vie juive au Maroc, Edizioni Addif, Casablanca, 1999.

[3] The first government formed after Morocco’s independence did however include a Moroccan of Jewish faith as Minister for Postal Services, Doctor Leon Benzaken. The National Consultive Council which was a sort of Parliament, also included among its members four Jewish Moroccan personalities, David Benazraf, Jo Ohanna, Jaques El-Kaïm and Lucien Bensimon.

[4] Michel Meir Knafo, Le Mossad et les secrets du réseau juif au Maroc 1955-1964, Biblieurope, 2008; Agnese Bensimon, Hassan II et les Juif , Seuil 1991.

[5] Haim Zafarani, op. cit.

[6] Daniel Rivet, Histoire du Maroc de Moulay Idriss à Mohamed VI, Editions Fayard, 2012

[7] Hilula in Hebrew literarily means “to shout with joy and rapture”; Zyara, an Arabic word that means “visit” is a Jewish and Muslim custom that consists in celebrating the commemoration of a saint with a pilgrimage to the place where he is buried.

[8] Authors who have addressed the subject of Jewish migration from Morocco include Marcel Benabbou with his novel Jacob, Menahem et Mimoun. Une epopée familiale; Edmon Amran El Maleh, Mille an, un jour et Essaouira Cité heureuse; Nicole Elgrissy, Si c’était à refaire. Films and documentaries we wish to mention are Adieu mères directed by Mohamed Ismaïl; Où vas-tu Moshé? directed by Hassane Benjelloun, and Tinghir-Jérusalem: les échos du Mellah di Kamal Hachkar.

[9] Emanuela Trevisan Semi, La mise en scène de l’identité marocaine en Israël: un cas d’ «israélianité » diasporique, Revue A contrario, 2007.

Cover Photo: A group of “indigenous” Amazigh Moroccan Jews (Courtesy of the specialized blog “Juif du Maroc” – http://juifdumaroc.over-blog.com).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.