“You who live near Rugunga, go out. You will see the straw huts of the cockroaches in the swamp. Those with weapons should immediately surround them and kill them.” These words, broadcast by Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) in April 1994, played a key role in driving one of the deadliest genocides in modern history by inciting violence, providing the locations of those in hiding, and urging listeners to kill. Over 800,000 Tutsi were slaughtered in just 100 days.

While the genocide raged, much of the Western media ignored or downplayed the horror, and the international community focused its efforts elsewhere. About 60,000 troops and billions of dollars were deployed in the Balkans, while Rwanda’s tragedy unfolded with insufficient response. This disparity reflects more than geographic proximity—it reveals an implicit hierarchy of crises, where some conflicts are seen as more urgent and deserving of intervention than others. If Rwanda taught us anything, it is that history tends to repeat itself in new forms.

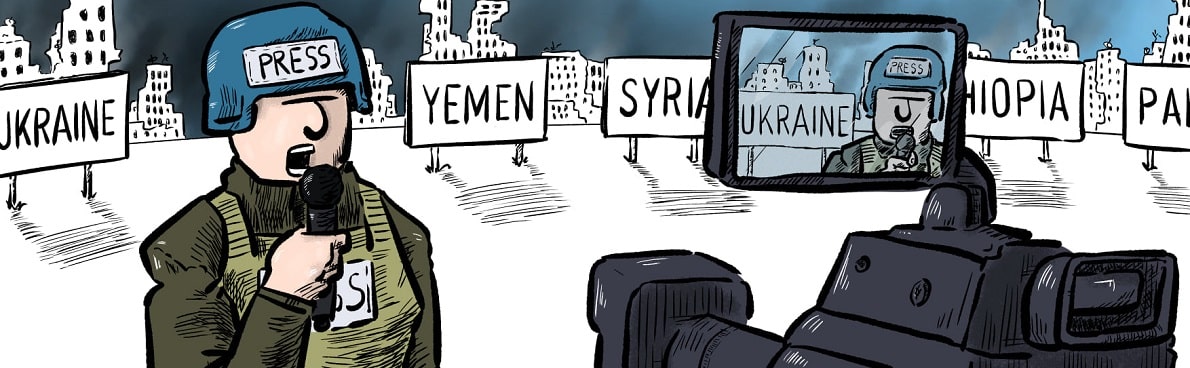

The lack of journalistic coverage during conflicts like the one in Rwanda is not just oversight; it is a form of media framing. Media framing is the act of selecting and organizing information to make sense of events, deciding what to highlight or omit. This inevitable practice in journalism shapes public perception and politics. Some conflicts receive extensive coverage, while others remain in the shadows. “In Ukraine, media coverage catalyzed swift responses, while conflicts like those in Yemen or the Democratic Republic of the Congo continue to be ignored,” explains Jan Klabbers, professor of international law at the University of Helsinki, regarded as one of the world’s leading experts in treaty law and international organizations. Silence, he warns, is never neutral: it frames crisis as much as active narratives do.

Narrative is always an act of selection. Emanuele Del Rosso, political cartoonist and communications coordinator at Display Europe, notes that narrative ethics lie precisely in the awareness of this selection and recognizing how it shapes the perception of reality. Every cartoon, he explains, is a frame that emphasizes certain elements while leaving others in the dark: “For every piece, I have to decide what to highlight and what to exclude. This is the power—and responsibility—of visual storytelling.” The same principle, he adds, applies to writing. Satire can shed light on uncomfortable truths through exaggeration, but it can also drift into manipulation. A striking example is the German magazine Der Stürmer, which built and fueled stereotypes to support Nazi propaganda. Yet, Del Rosso stresses that falling into propaganda unintentionally is rare: a crucial distinction that separates satire from deliberate disinformation.

Similarly, the selection of what to report and how can also reinforce dangerous stereotypes or oversimplifications in journalism. In 1994, the media often reduced the Rwandan massacres to an “ethnic issue,” strengthening simplistic narratives. This pattern persists today: conflicts far from the Western world are frequently dismissed as tribal disorders. Such framing trivializes crises rooted in colonial legacies, depriving victims of dignity and perpetuating the idea that some lives matter less.

The Global Peace Index 2024 lists 56 ongoing conflicts. This staggering figure, however, clashes with the reality of media coverage, which focuses only on a handful of crises, leaving many voiceless. Confronted with this silence, one question naturally arises: what will be the next massacre we leave in the dark?

It is not just about media capacity but political will. Some atrocities enter history books, others sink into oblivion. Before the Holocaust, genocides like that in Congo under King Leopold II of Belgium scarred humanity. Between 1885 and 1908, millions of Congolese were enslaved, and around ten million died from violence, abuse, and disease. Yet, the Congolese genocide remains on the margins of collective memory.

The influence of media framing is a double-edged sword. It can shape public awareness and sway political decisions, directing government agendas and resources. In 2015, intense media focus on the Syrian refugee crisis led European governments to adjust immigration policies and boost aid. Yet, its impact is fleeting. Klabbers notes that media cycles limit the ability to sustain political momentum: “We paid a lot of attention to Russia and Ukraine in February 2022; now it’s still a story but no longer on the front page.” Media interest is volatile and limited. “When the war in Palestine broke out in October 2023, the media flew away,” comments Del Rosso, referring to one of his cartoons where Zelensky desperately clings to flying newspapers, being pulled away by the Middle East crisis. The message is clear: media focus is ephemeral. This selective shift reflects editorial choices, geopolitical interests, and a psychological component that prioritizes conflicts closer to home, both culturally and geographically. “Distant wars, like those in Yemen or the DRC, remain in the background,” concludes the illustrator, “but as news consumers, we should ask ourselves what we don’t see. Why doesn’t this conflict have faces and stories?”

Klabbers observes that the media’s role goes beyond reporting: “If an event doesn’t get attention, people don’t know what’s happening, won’t make decisions, and won’t take action,” he says. The lack of reports coverage sends a message that the issue is not urgent, he explains. At the same time, he warns, while media attention can trigger action, it should not be overestimated. “Journalism shapes the narrative, but it rarely dictates how the course of international law is applied. That power lies elsewhere. And the Rwandan genocide made that evident,” he concludes.

Despite available reports, the UN Security Council still hesitated. Labeling the massacres as genocide would have triggered intervention obligations. This hesitation was not due to a lack of information but rather a calculated effort to avoid invoking the Genocide Convention, which legally obliges signatory states to intervene. Klabbers succinctly explains this paradox: “If you call it genocide, you may trigger the Genocide Convention, hence an intervention.” And so, through a linguistic paradox, the horror was allowed to continue undisturbed. In other crises, like those in Yemen, Sudan, Myanmar or Palestine – a case often subject to contention – hesitation prevails in applying binding labels that could carry legal, political or diplomatic consequences, even when patterns of ethnically, politically or ideologically motivated violence are evident. New contexts, new borders. The same fear of uttering words that compel action. Del Rosso echoes this sentiment among the public: “When I draw Ukraine, the reaction is immediate. When I illustrate forgotten wars, social media engagement is minimal,” he says.

Yet, the media’s role goes beyond mobilizing public opinion. “Media coverage, while not preventing violence, can promote post-conflict justice,” Klabbers emphasizes. The media can become key witnesses, helping preserve historical memory and build documentary evidence that can later support judicial proceedings. Images, videos, and reports were essential in the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) trials, where they demonstrated the chain of responsibility for war crimes. But the scholar warns about the limits of this approach: “The media are not investigators. Their evidence, while valuable, is not always neutral.” The media do not replace on-site investigations conducted by forensic experts and investigators, but they complement them. Without them, some truths might never surface.

If on the one hand, the media can act as essential observers and contribute to post-conflict justice, on the other hand, they can also fuel dynamics of violence and manipulation, reinforcing prejudices and delaying accountability. Media influence often seeps into conflicts through narratives that justify military actions or distort collective understanding. This, for example, occurred in Russia, where state media presented the invasion of Ukraine as a “denazification operation”, and in the United States, before the Iraq war, where the media amplified narratives about weapons of mass destruction, facilitating intervention. This raises questions about the legal and ethical role of the media: can the media be held accountable by international law even when incitement is subtle and indirect?

While international law punishes explicit incitement, it lacks clear regulation on media manipulation in wartime. Rwanda’s case showed that direct instigation is punishable, but subtler propaganda shaping public perception without explicit calls for violence evades legal boundaries. Klabbers notes that media outlets are rarely held accountable if they report what they believe to be facts, unless they openly incite violence, as was the case with RTLM in Rwanda. Perhaps this is the very nature of journalism, which operates within fluid ethical boundaries and makes it difficult to fully legislate media behavior. Regulation may curb extreme cases, but the challenge remains in addressing the fine line between reporting, framing, and manipulation.

If laws fail to contain media distortions, it falls to individuals to question their perspectives. If the role of storytellers is to shine light on the shadows the world ignores, it is up to readers and listeners to decide what to see and what to leave in the dark. Ultimately, the real question may not be what the media shows us, but what we consciously choose to see.

Cover photo: “Outside the frame” by Emanuele Del Rosso (DelRosso Studio). All rights reserved.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).