Strengthened by the possibility of success in the upcoming European parliamentary elections, the coalition partners in the current Italian government — Lega and M5S (Five Star Movement) — continue to scout for new allies in the EU. While the M5S trudges forward in a search for a role in Brussels, Matteo Salvini’s Lega could end up redefining the balance across the European right wing by means of a new relationship between conservative and populist parties.

From taking down to taking over the EU

As a member of the ENF (Europe of Nations and Freedom group), Lega sits with the Austrian FPÖ, the Dutch PVV and its longtime counterpart, Marine Le Pen’s RN (Rassemblement National). As predicted by current polls, ENF parties stand to achieve a significant increase in votes in comparison to the 2014 EU elections. Lega itself could see an increase from its present 6 seats to around 29, while the right-wing populists could win close to 60 seats in total altogether. With this result, the ENF would find itself in fourth place, so to speak, among the EU parliamentary groups, which in itself is not an earth-shattering result.

But considering that another Eurosceptic formation, the ECR (European Conservatives and Reformists), will likely collect around 50 seats, and a third grouping, the EFDD (Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy) may reach 45 seats, the next European Parliament could see more than 150 seats occupied by (mostly right-wing) populists and Eurosceptics. In other words, if anyone wanted to pull the entire EU toward the right, the chance may well be close at hand. This, it has to be said, will not happen overnight, but it could become a viable long-term project.

Salvini’s main tactic is now to look outside the current ENF area and the overall strategy is clear: to become the principal interlocutor for the EPP and throw socialists, greens, and liberals out of the EU control room. After all, it is not necessary to take the EU down if you can simply take it over.

A few weeks ago, Salvini met with Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of the Polish PiS (Law and Justice party), a member of the ECR group. On this occasion, Salvini referenced a new “Italo–Polish axis”, and noted that such an alliance offers to bring “new blood, new strength, and new energy” into the EU, statements which reach far beyond standard Italian nationalist claims.

Last August, Salvini met with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in Milan, where the two leaders road tested a potential political bromance. The Italian minister was not, as he stated, asking Orbán to leave the EPP, but he did express concrete hopes for future collaboration.

Meanwhile, in an interview with Italy’s La Stampa, Manfred Weber, the EPP candidate for the European Commission presidency, has openly declared the need for compromise with both Orbán and Salvini.

To summarize the issue, if until last year, the EPP had tried to keep its right-wing parties on the margin, now the opposite may happen. After the elections in May, the EPP (which is estimated to drop to fewer than 180 seats) will eventually look for an alliance with the liberals and/or the socialists (the polls predict around 80 seats for the former and 133 for the latter). But a German-style grand coalition for the EU will not avoid a growing connection between the right wing of the EPP and the national-populist medley.

After all, Salvini’s Lega was, and in some senses still is (though with much room to grow), a political ally of Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party, which remains a relevant member of the EPP.

Austria’s current government is also especially emblematic of a new conservative-populist model, where the center-right ÖVP (EPP) and the right-wing FPÖ (EFN) became a lab experiment for the cross-contamination of traditional Christian-democratic and populist-identitarian forces.

Salvini meets the Visegrád Group

Of course, none of this addresses the paradox of a coherent European populist alliance: coordinating a transnational bloc of nationalist parties remains a prohibitively difficult project.

In Poland, Salvini has already had to confront the key difference between Lega and the PiS: Russia. If Lega, along with the French RN, is one of the most pro-Russian parties in Europe, the historically anti-Russian PiS, like many other leading forces of the Visegrád Group, typically push for more sanctions against Moscow and a stronger NATO presence in eastern Europe. This is because politics are important, but geopolitics can have much more tangible consequences.

On the top of this, the Visegrád Group is hardly Italy’s best friend when it comes to financial flexibility within the EU, which is a key feature of the deficit-oriented budget of the current green–yellow government in Rome. As is well known, identitarian populist parties do not think much of European solidarity.

This may be even truer when it comes to the German extreme right AfD (which recently called for a Dexit) and the aforementioned Austrian government, one of the biggest supporters of balanced national budgets in the EU. When it comes to the Italian–Austrian relationship, it is also useful to note other recent tensions between Italian populists and the Austrian right=wing, in particular regarding the Alto Adige–South Tyrol issue (a perfect example of what happens when canonic nationalisms resurface from the past).

For his part, Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz shut down any possible alliance with the Italian Lega in an interview with the Financial Times. Statements like this give many European liberals, social-democrats, and conservatives a reason to underestimate the power of the populists in the next EU Parliament and to predict that—despite an increase of seats—groups like EFN will end up self-sabotaging through their own contradictions.

But despite these predictions, things could still turn out quite differently, especially if we consider a crucial and decisive element: the emerging of an entirely new kind of Europeanism.

Europeanism as the new identitarianism

Beyond these quarrels and contradictions, a certain ideological glue holds the new populism and classic European conservatism together. This glue is the idea of a new European identitarianism, merging the agendas of national-conservatism, anti-liberalism, anti-socialism, western cultural homogeneity, and even secularism (in this case, for expressly anti-Islamic purposes). This European identitarianism does not cling to dull, nostalgic ideas of restoring the pre-EU national order, but neither is it aligned with the prevailing principles of the current EU.

This idea of European identitarianism takes shape in a two-factor context. The first factor is the multipolar situation of world politics that, at present, fractures diplomatic and economic collaboration, and accelerates geopolitical conflicts between major strategic areas. This makes it almost natural that Europe would try to find its own compact identity. The second and more crucial element, though, is how this compactness is given a conservative-populist twist through direct confrontation with internal and external otherness. In other words, through harsh refutation of multiculturalism inside European countries, and through the ideological war against immigration toward European countries.

More than Euroscepticism, the central appeal of the European populists for core supporters has been the failure of traditional Europeanist parties to develop coherent strategies on questions of immigration and multiculturalism. But if the EU were to change its approach on these critical issues, many populist forces would contemplate giving up the idea of invalidating the European project as such, Salvini’s Lega being just one of those. At the same time, a growing number of European conservatives may be ready to embrace the new European identitarianism and harsher politics over multiculturalism and immigration (with the exclusion of productive labor immigration) if this would let the EU retain its global standing—and the bloc’s economic heft, which is indispensable in a multipolar world.

Against this background and given the nature of the current populist parties, rather than wading into the difficult politics of undermining the European Union, this type of new European identitarianism could eventually simply push for a substantive overhaul of the entire liberal-democratic framework that underpins it, in favor of a European “ideal” that is more nativist and illiberal.

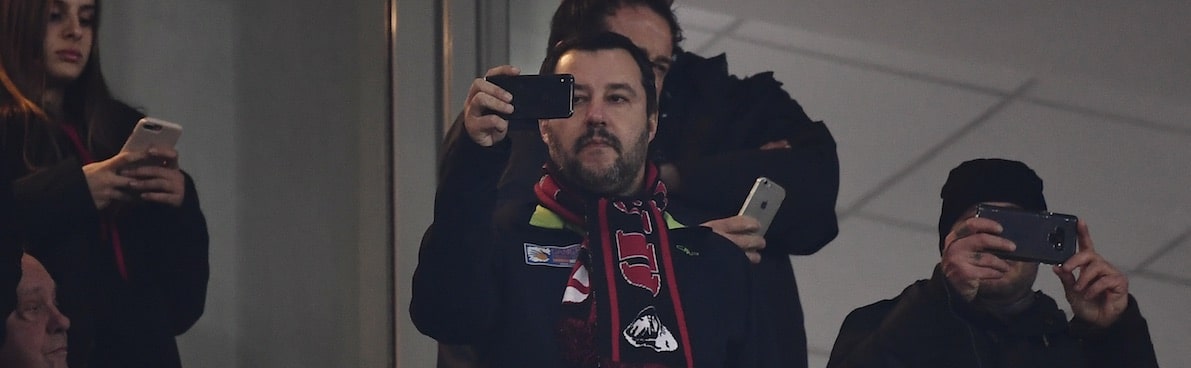

Photo: ARIS MESSINIS / AFP

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook. And share our contents.

If you liked our analysis, stories, videos, dossier, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).