In our fast and consumerist digital way of life, we have forgotten how important it is to disagree. When we look at the world through the lenses of our mobile applications and social media, we only see a fictional image reflecting what we want to hear and to see. This is the well-known “Daily Me” – a process led by various algorithms, aiming at showing the user the content that he or she expects to see, thanks to a prediction based on his interests, tastes, ideas, and friends. Cass Sunstein, in his work #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media extensively analyzed this dangerous vicious circle in which people socialize and interact virtually with people that have similar thoughts and tastes, while sharply opposing anyone different. This widely debated and studied phenomenon of polarization is very much related to the contemporary tragic event of the terrorist attack on the French history and geography teacher, Samuel Paty, in front of a school in the Parisian suburb of Conflans-Sainte-Honorine.

In fact, what is behind this event is not only an act of terrorism, but more fundamentally the principle of accepting the rules of disagreement. What permitted a barbarian crime does not concern only the person responsible for this action; it is also related to a grey zone of those that accused the teacher and posted on social media a distorted image of the events.

What happened in a lecture on freedom of expression as part of the program of Moral and Civic Education (a course created in 2015 in all public schools in France) was a concrete example of freedom of expression as a freedom to disagree. Mr. Paty showed the Charlie Hebdo cartoons that portray a very provocative and to some extent shocking image of the Prophet Mohamed. Nonetheless, even though some cartoons may be disturbing or offensive to some audiences, overall, they do not discriminate against specific believers of a faith while questioning ironically and provocatively ideologies and religions. This act was not meant to blindly praise the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo’s editorial policies. It rather was meant to engage a debate about the boundaries of freedom of expression, since Charlie Hebdo cartoons nowadays have become a symbol transcending the content of their image. Sadly, today they also represent a target for Islamist terrorists.

After the terrorist attack against the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris in 2015, where 12 people were murdered, the meaning of these cartoons has gone beyond their initial content. Because of the horrific attempts to silence and censor them, today they epitomize freedom of expression. As a matter of fact, Paty’s lecture was framed in the context of the trial of the terrorist attack of 2015 (which later found 14 people guilty) and just a couple of days after another terrorist knife-attack near Charlie Hebdo‘s former offices.

Now, should it be forbidden to speak about or simply show Charlie Hebdo cartoons? Or by contrast, would it not be useful to display them in order to discuss their role to a diverse and multi-faith class? Some students might find them too aggressive and provocative, other students might find them thought-provoking. In any case, censorship is not an acceptable solution. Since these cartoons have transcended their initial message, it is urgent and fundamental to continue to talk about them, even in case of firm disagreement. Mr. Paty, through his lecture, meant precisely to engage a debate about it, avoiding a blind and Manichean polarization.

Contemporary Dilemmas

Notwithstanding, many dilemmas remain unsolved. The first one refers to the offline/online divide. The act of showing Charlie Hebdo cartoons to students, which aimed at producing debates and awakening critical minds, failed in its attempt. With a deep sign of respect, he said that students who may feel offended by the cartoons could close their eyes or leave the classroom. But by doing so, the French teacher involuntarily divided his students. This issue was later solved within the context of the school and without any major incident. However, the situation escalated when the father of one of Mr. Paty’s students, who had not attended his class, filmed a video criticizing the teacher. The father was very active in the online radical “Islamo-sphere” as described by Gilles Kepel in this dossier.

The video circulated so widely on the social media in France and abroad that it was quickly shared on Islamist networks and brought to the attention of the future murderer, Abdullakh Anzorov, an 18-year-old Chechen based in France. Mr. Paty thus became the target of an online hate campaign in a polarized social media framework. A framework based on a binary interpretation of the world: “0 or 1”, “followers” or enemies. The polarization of ideas and the mechanisms of virality have led to the quest for an exemplary scapegoat under the banner of a perverted form of intolerant Islamism. This shows the extreme gap between an offline reality, where debate and discussions can occur in a myriad of rational arguments and nuanced theses, and an online dichotomist viewpoint that can characterize the social media landscape. Since this latter has become a powerful tool for Islamist activists, a further analysis should be focused on the nexus between the terrorist attack and the grey zone of the online hate campaign that preceded the tragic event.

Secondly, there is a linguistic dilemma at stake, the problem of translating the French concept of laïcité to other languages, since laïcité is specifically related to an anti-clerical French tradition as clearly explained by Philippe Portier in this dossier. Remarkably, the only similar foreign word is the Turkish laïklik, although nowadays it has a completely different use. The word secularism cannot really unfold all meanings of laïcité. Undeniably, most Anglophone media did not really understand the French approach to this event – and the quarrel between President Emmanuel Macron and part of the American media is strikingly explicit on this regard. Besides this, the normative framework regulating freedom of expression and blasphemy is very different if we compare France to other countries, especially Muslim ones, as Nader Hammami analyses.

Finally, there is a double game mixing local and international stakes, to the extent that different actors have used this event for strategic and political purposes both at a domestic and international level. The dispute between Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and President Emmanuel Macron, as well as the boycott of French products in some countries, are telling cases of this, as is well described by David Rigoulet-Roze.

The Tradition of Dissent

With regard to education, creating sterilized and polished classes should be avoided. They have already been sterilized from viruses; let’s not sterilize them from critical thinking, nor from the right to blaspheme and freedom of expression by admitting as many interpretations and viewpoints on sensitive debates as possible.

During the ceremony of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade, the winner of the Year 2020 and former Nobel Prize winner, Indian economist, and philosopher Amartya Sen, reminded us how dissent and disagreement are fundamental by quoting Kant’s noted definition of Enlightenment. The most common interpretation of Enlightenment refers to a specific historically and culturally situated way of thinking and behaving. Yet, the German philosopher wanted to confer another meaning upon it. According to Kant, Enlightenment is a duty and a behavior: to dare to use one’s own understanding and not passively accept others’ directions. Autonomy and critique, which coexist in his view, allow every individual to distinguish a public from a private use of reason. The latter relates to what people do in their daily life in public offices, as a teacher, as a priest, as a soldier, obeying and following the norms of conduct. On the contrary, the former is what people do as scholars in front of a global public of readers, no matter their role in the society. To be a scholar means to be free to speak to all, defending one’s own ideas in an autonomous way. An official can obey his superior’s rule while in office, but as a scholar has the freedom and civic duty to question this rule if he or she does not agree with it. Similarly, a citizen must pay taxes and obey the State, but as a scholar he or she can criticize these laws and try to change them. A man is truly a man when he is free in the public use of his reason, if he is free to say and write what he thinks. While the private use of reason is related to the main norms of belief, behaviors, and customs belonging to a specific context and culture; the public use of reason rests upon one’s own individual ability to think. Therefore, it cannot be linked to a particular culture.

Certainly, choosing to use the public use of reason entails an act of courage, an exit from the comfort zone of common behaviors, traditions, and rules and from the space of socializing, speaking and behaving with people with the same tastes. Freedom of conscience and autonomy of thinking are the hardest paths to follow. This act of courage is to choose the responsibility of liberty – precisely what the Grand Inquisitor in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov called the “unbearable burden”. In a rich and inspiring analysis, French philosopher Frédéric Gros defined it as a “refusal of mute obedience”.

Education and Dialectics

Undoubtedly, the tradition of freedom of expression that entails the liberty of teaching is grounded in dialectics. Remembering Socrates and Plato is a way to understand the fertility of dialogue based on disagreement. Every debate is a mutual construction that does not have a predefined answer. In the Theaetetus, Socrates employed the famous metaphor of the midwife who helped others give birth to the wisdom that was in them. Similarly, according to the Latin etymology educere means “bringing out, leading forth”.

Likewise, science is based on errors and on the debate of conflicting theories. Karl Popper explicitly defined as “scientific” every theory which is falsifiable. This is precisely what distinguishes science from faith, the possibility of error and therefore a space for disagreement. There is not one truth that should be unveiled to students; rather a methodology of enquiry, analysis and critique that should be taught to them and practiced by their teachers. Samuel Paty did not blindly celebrate French blasphemy; he tried to teach and demonstrate freedom of expression with its difficulties. The audience might not accept blasphemy, considering it a form of offence, yet the reaction to this debated question cannot be rendered in a polarized “0-1 mode of thinking” – as the logic of social media works. Education is thus grounded on error and dissent – this is what distinguishes it from ideology, dogmatism, or faith. The act of dissent is what allows knowledge to progress effectively.

Following Paty’s terrorist attack, Edgar Morin suggested the adoption of a complex approach in order to tackle the problem of divisive binary thought. According to him, a critical mind entails the vitality of the “curious spirit”. It supposes self-critique, which the act of teaching should awaken to enable each student to reach a form of reflexivity and self-critique[1]. Mr. Paty brought to his class a case for discussing the boundaries of freedom of expression and liberty of disagreement, within a tolerant context – what John Rawls would call “overlapping consensus”. Yet, towards intolerance there should be a firmly opposed behavior. Accepting the art of disagreement is what permits individuals to progress, to exchange and to be in a dialogue. As John Stuart Mill stated, “The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error”.

References

[1] In the original: “L’esprit critique suppose donc la vitalité de l’esprit interrogatif et de l’esprit problématiseur. Il suppose aussi l’autoexamen, que l’enseignement doit stimuler, afin que chaque élève accède à une réflexivité qui elle-même permette l’autocritique ; l’esprit critique sans esprit autocritique risque de verser dans une critique incontrôlée de ce qui nous est extérieur. Que serait un esprit critique incapable d’autocritique ?”

Camilla Pagani PhD, is Lecturer in Political Theory at MGIMO University, Moscow, and a member of Sciences Po Alumni.

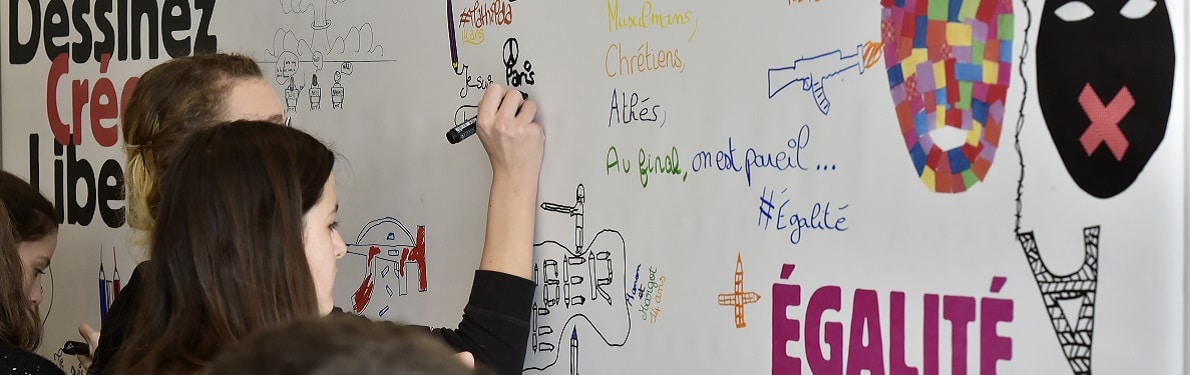

Cover Photo: Georgees Gobet / AFP

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).