One week ago, Donald Trump secured a resounding victory over opponent Kamala Harris in the 2024 US elections, primarily due to a country-wide shift to the right. Swing states like Georgia and Michigan that were previously blue, are now red and urban areas – historically Democratic bastions – have shifted their favor considerably towards the Republican party. We asked Jeffry Frieden, Professor of International and Public Affairs and Political Science at Columbia University what was motivating voters and whether this rightward shift will mean for democratic values and whether Trump will be able to live up to his lofty election promises.

Has liberal democracy been sacrificed in favor of short-term economic benefits? Why have low-income voters, who have traditionally voted Democrats, swung so heavily in favor of Republicans?

We have to be careful about drawing conclusions regarding the state of liberal democracy from this election or recent elections, where people appear hesitant about or even reject what we might consider liberal democratic principles. Most of the evidence we have indicates that people don’t vote based on principles oriented towards liberal democracy. In the American context voters often downplay, ignore or may not even believe charges levied against their opponents that they pose a threat to democracy.

In the recent election campaign, Republicans painted the Democrats as threats to democracy, and Democrats did the same with Republicans. This makes it hard to read into the election results. Social-scientific research seems to suggest that democracy, as a principle, doesn’t rank very high in the minds of most voters. To put it bluntly, most voters want candidates who will pursue their goals – even if that means using methods that some might consider undemocratic. There may be limits to this. In the American context, blatant military attempts to override the clear will of voters would likely be countered by both institutions and citizens. However, the election results, as well as social scientific evidence, are ambiguous on this point, so I wouldn’t pull the fire alarm quite yet. It does seem that more Americans on both the left and the right are increasingly open to using undemocratic means in search of goals they see as crucially important. The reality is that there’s a growing willingness across the political spectrum to support actions that fall outside the norms of established institutional democracies in pursuit of specific ideological or political goals.

In terms of economics, the Republican platform appears to capitalize on perceptions of financial insecurity. How have decades of economic deregulation – policies that haven’t typically benefitted working class voters – become scapegoated into key issues like inflation and immigration?

I think we can identify two main strands in the Republican campaign, which also appear in public opinion polls: one focuses on the economy, and the other on a range of social or cultural issues. I’ll start with the economy. Both focus groups and public opinion polls make it clear that people are unhappy with the state of the macroeconomy, and their dissatisfaction is legitimate and understandable. The economy in the U.S. has been growing, but virtually all that growth has largely bypassed the middle class—a trend persisting for over 30 years. In focus groups of undecided and swing voters, published in The New York Times and other outlets, most expressed that things were better under Trump than under Biden. In terms of average growth, such as GDP per capita, the difference is modest. But if we look at real median household income – that is, the income of the 50th percentile, by definition the middle class – it rose by 8 to 10 percent during the Trump years and was flat or slightly declined during the Biden years.

And the reason was inflation. Middle-class incomes didn’t keep up with inflation over the last four years. Democrats could argue that the economic growth will eventually have positive effects, but people felt the impact directly in their pocketbooks: prices rose by on average 25 percent, while salaries increased by only 15%. This created a strong sense among many voters – who might otherwise be indifferent to social or cultural issues – that there was a notable economic difference between the Trump years and the Biden years.

Nonetheless, hardwired political polarization seemed to indicate that many had decided who to vote for well before November 5th.

In the American system, around 85 to 90 percent of voters consistently support the same party, so elections largely come down to the remaining 10 to 15 percent in the middle. Every four years, this group essentially votes on whether they think things are going well or poorly, giving a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” on the current state of affairs. This time, that 10 to 15 percent in the middle gave a “thumbs down” economically. To understand what’s driving American politics, it’s essential to focus on a specific group: voters who supported Barack Obama twice, then Donald Trump, then Joe Biden, and now Trump again. This group – about 8 to 10 million people, or roughly 3 to 4 percent of the electorate – are the classic swing voters. They tend to be working- and middle-class and represent diverse ethnicities. Notably, over 20 percent of Black men voted for Trump this year, along with increased support among Black women and a substantial rise in Hispanic and Latino support, from about 30 to 45 percent according to exit polls. This pattern challenges any narrative that the election was solely a backlash by white voters against minorities, as significant portions of minority communities supported Trump – more so than in 2016 or 2020.

And what about the social-cultural issues?

Traditionally, “social policy” refers to issues like unemployment insurance, disability insurance, and health care. But today, when people discuss social issues, they’re often referring to topics like gay rights, transgender rights, minority rights, and identity politics. If I had to summarize this set of issues on the social-cultural divide, I’d say much of it centers around identity politics—which is an interesting shift in itself.

The first time I encountered the term “identity politics,” it was used to describe white supremacy – attempting to convince white workers that they had nothing in common with Black and Hispanic workers. Today, “identity politics” has a very different meaning. It now refers to emphasizing one’s identity as LGBTQ+, trans, Black, Hispanic, Jewish, or any other identity category. This has become popular on college campuses and in liberal, college-educated cities. However, it’s highly unpopular among the American working and middle classes, who view it as a divisive force and resist claims for special treatment. This is perhaps more of a cultural or social issue: less than one-third of Americans hold a college degree, and much of this rhetoric resonates mainly with those who do. Two-thirds of Americans, without a college degree, don’t identify with the issues that are culturally and socially important to people in places like New York, San Francisco, or Chicago.

There’s a significant cultural and intellectual divide in the country about how society should be understood, what role government should play, and how individuals relate to society. This divide extends to issues like law enforcement, homelessness, and what some see as a broader debate about social and human rights versus the preservation of the environments and communities in which they live.

So, Democrats as not taking law and order concerns into account still seems to be the perception among voters who are feeling increasingly insecure?

There’s a strong sense among many people that progressive policies have led to lawlessness, insecurity, and other negative consequences. I’m trying to explain why some believe that policies associated with the progressive wing of the Democratic Party have gone too far. While many would agree that addressing issues like homelessness and caring for the poorest members of society are important, they feel these policies have been taken too far – often in ways that infringe on the rights of others. This is a common view, even in liberal, Democratic cities. In fact, Trump did much better in places like New York, San Francisco, and Chicago in 2024 than he did in previous elections. One key lesson from this election – and many others in advanced industrial countries over the past 5 to 10 years – is that the center-left must seriously consider how and why it has lost the support of the working and middle classes.

What alternatives can Democrats pursue to win back working-class voters, particularly those in communities negatively impacted by trade and economic liberalization, without relying on social safety nets that may be seen as handouts?

I think people want jobs, not handouts. In extreme situations – if someone is starving or disabled – direct support is almost always welcome. But here we’re talking about entire regions, whole towns and small cities that have been in decline for 20, 30, even 40 years, caught in a downward spiral that’s difficult to escape. To address this, we should focus on the broader problems facing these communities as a whole. Instead of giving individuals direct aid, we could invest in schools, local infrastructure, and incentives for private enterprises to invest in the community. In fact, many initiatives from the Biden administration – such as the infrastructure bill, the CHIPS Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – are steps in this direction, aiming to make it attractive for private businesses to build facilities and create jobs in communities that have been neglected for decades. Politically and economically, I believe the best way forward is to invest in the communities where people live.

One problem that Biden and Harris faced is that these kinds of efforts take time to show real results. Investing in roads, infrastructure, and schools can eventually turn around struggling communities, but it doesn’t happen overnight. Still, I believe this is the right approach: implementing policies that help communities pull themselves up collectively. Key areas to focus on include education, infrastructure, and what we call “workforce development,” which has been very successful. This approach involves government coordination with community colleges, high schools, and the private sector to ensure people are learning the skills businesses need.

Could this be applied to these more affected communities?

One of the paradoxes of the current economy is that, despite labor shortages, there’s a skills mismatch. Businesses need workers with specific skills – such as coding or advanced literacy – but struggle to find them in places like Kent, Ohio, or Erie, Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, areas like New York and San Francisco, with highly educated populations, aren’t where the demand is greatest. This skills gap reflects both a societal and governmental failure to address the economic needs of long-declining regions.

Why do you think the markets reacted so positively to Trump’s election, given the potential inflationary impact of his economic policies and deportation plans? Will the effects of any inflation simply be deferred, with the economy instead benefiting from recent policies like the CHIPS Act and the IRA?

I think the main reason the markets surged after Trump’s election is that, if Trump stands for anything, it’s lowering taxes and deregulating business. Unsurprisingly, this is very popular with wealthy individuals, as lowering taxes on the rich, reducing the corporate tax rate, and deregulating business – something Trump did previously – is favorable for most businesses. However, there are clear contradictions in Trump’s economic agenda. For example, tariffs are highly inflationary as they directly raise prices, and tax cuts can also drive inflation. Given that most government spending is already locked into areas like Social Security, Medicare, and defense – programs Trump says he won’t cut – the deficit will grow and almost certainly add to inflation.

However, at this point, the U.S. government has shown it can borrow extensively without creating major inflation, and the Federal Reserve remains independent. As Jerome Powell says, the Fed will stay independent as long as he’s in office, which could counterbalance inflation. But Trump is voicing a classic populist approach: promising tax cuts and deregulation to the wealthy, while also promising lower taxes and more spending to the middle and working classes. It’s a bit “pie in the sky”; I can’t imagine that even half these promises will be met. But we’ll have to wait and see.

So far, we’ve focused on what the results reveal about the U.S. What do you think are the global repercussions of this election?

My field is international politics and economics. While nearly all the focus in the U.S. has been, and likely will continue to be, on domestic issues, I believe some of the most serious implications of Trump’s victory are international. Whatever one might say about Trump’s domestic economic policies, he has been consistently clear—both in his first administration and now—that he doesn’t believe in the multilateral institutions that have defined the Western world since 1945. He doesn’t view these institutions as serving American interests and doesn’t think the U.S. should follow the established rules and norms that have governed international trade, finance, and investment over the past 80 years. I think this direction could lead to very difficult and troubled times in the international economy. Ignoring the multilateral and institutional foundations of the global economic order that have been built over decades, I believe, is not in America’s interest, nor is it conducive to a stable and prosperous world. But it seems clear that this is the path the Trump administration is likely to pursue.

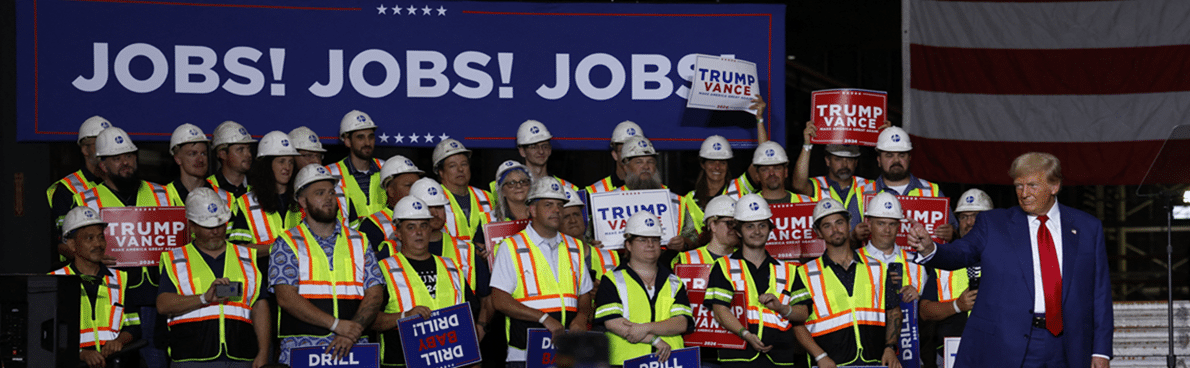

Cover photo: Donald Trump arrives to speak about the economy during a campaign event in Potterville, Michigan, on August 29, 2024. (Photo by JEFF KOWALSKY / AFP)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).