The first statement in response came from Evin Prison in Tehran: “The global support and recognition of my human rights advocacy makes me resolved, more responsible, more passionate, and more hopeful,” said Narges Mohammadi, the Nobel Peace Prize’s latest laureate. “I also hope that this recognition makes Iranians protesting for change stronger and more organized” she added. In their announcement, the Norwegian Nobel Committee recognized her extraordinary activism and stated that the prize was in honor of “her fight against the oppression of women in Iran and her fight to promote human rights and freedom for all.”

Narges Mohammadi’s first (and so far only) statement came in writing to The New York Times from Evin Prison – the paper had interviewed Mohammadi last spring, through written messages and sometimes on the phone, and had written up an extensive profile on her last June.

Mohammadi’s voice has been heard far beyond the walls of her confinement, particularly over the past year. In support of the protests happening all over the country, which had also managed to penetrate into the prison yard, she helped organize acts of collective disobedience, auditory protests – like when inmates sang the Iranian version of Bella Ciao over their cell phones. She has held seminars for other female inmates on human rights; in December she released a report on the physical and sexual abuse suffered by female inmates, based on testimonies she collected. Earlier she wrote a book on the emotional impact of solitary confinement, also with testimonies collected in prison. She sent complaints and articles to the outside world. In May her right to phone calls had been revoked after she posted a condemnation of human rights violations in prison on her Instagram. In short, detention has not stopped her dogged struggle, and that alone says a lot about who the new Nobel Peace Laureate is.

Born in 1972 in Zanjan, central Iran, Narges Mohammadi was just a few years old when a people’s revolution overthrew the Pahlavi monarchy. She thus belongs to a generation that grew up under the Islamic Republic, the daughter of those who had enthusiastically participated in the revolution only to see themselves locked in a cage of veils and prohibitions: and they soon began to give battle to reopen spaces of freedom for women, and for everyone. Mohammadi often recounted that political activism started at home, among the members of her family. Her commitment emerged during college, which she attended in Qazvin, a city northwest of Tehran, where she studied nuclear physics – and founded a student collective. During her college years, she also attended seminars on politics and civil society given by a university lecturer and intellectual rather well-known in critical circles, Taghi Rahmani, whom she married in 2001.

The couple settled in Tehran, where they both continued to work in civil society organizations. The couple had twins, but the family was not able to stay together long. In fact, Rahmani was arrested almost immediately, spent two years in pre-trial detention before charges were brought against him, then suffered more arrests – always for his written critiques of the political system. This is also why she began to concern herself with the plight of prisoners, particularly prisoners of conscience who were often imprisoned arbitrarily, without knowing the charges, without access to legal counsel of their choice, or without knowing the evidence against them. Not long after, she herself was soon in and out of prison.

Over the past three decades, Narges Mohammadi has been among the most active figures in civil society activism. During the presidency of reformist Mohammad Khatami from 1997 to 2005, Iran was experiencing a time of great internal openings. Independent newspapers and associations were flourishing and internal clashes more hardline sector of the institutional system were taking place on the question of freedom and rights. Mohammadi worked with the Center of Human Rights Defenders, created by a group of lawyers including Shirin Ebadi, herself a 2003 Nobel Peace Prize laureate – along with other figures such as Nasrin Sotudeh, also a lawyer who suffered long years of detention and judicial persecution. One of her campaigns was against the death penalty. The Center for Human Rights Defenders was shut down in an arbitrary act by the judiciary in December 2008, the premises cleared by security agents, during the crackdown ordered by then-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad; Ebadi left the country shortly thereafter and has lived in exile ever since. Around that time Narges Mohammadi also lost her job as an engineer, fired by the Public Works Authority (it would seem, under pressure from the government).

Moments of relative détente and repressive tightening have continued to alternate in Iran; the work of human rights activists, however, has never been easy. But certainly the phases of Tehran’s international isolation – such as the one that began when then-U.S. President Donald Trump revoked the US’s adherence to the agreement on Iran’s nuclear program (which Tehran had hitherto complied with) – are also those in which the Islamic Republic’s most extreme currents are strengthened.

Narges Mohammadi has been arrested thirteen times and convicted five. She is currently serving a 10-year sentence for attacking state institutions and national security. More charges have recently been brought against her, which could lead to new convictions. Meanwhile, Taghi Rahmani lives in exile in Paris with their children Ali and Kiana, now 16 years old. Their mother has not seen them in person for eight years; she talks to them on the phone, or in video calls in the rare intervals when she is out of prison.

Narges Mohammadi had received other awards in the past for her human rights work. The first was the one bestowed by the Alex Langer Foundation in 2009, which had sought to recognize the existence of “another Iran”: at that time Mohammadi was part of an array of writers, artists, and social activists who were fighting against the logic of repression, but declared themselves opposed to threats of military action against Iran, which would have further aggravated the human rights situation in the country. Earlier this year, she was given the “Freedom to Write” award by PEN America as well as the UNESCO World Press Freedom Award.

The Iranian government commented acrimoniously on the news of Mohammadi being awarded the Nobel: “The Nobel Committee acted in line with the interventionist and anti-Iranian policy of some European governments,” said Tehran’s foreign ministry spokesman: “It awarded a person convicted of repeated violations of the law and criminal acts, and we reject this politically motivated gesture.” The reaction comes as no surprise; the Iranian government does not like criticism and has always dismissed any charges (“interference”) on human rights – even the Nobel Prize to Shirin Ebadi 20 years ago had garnered sour comments from Tehran authorities.

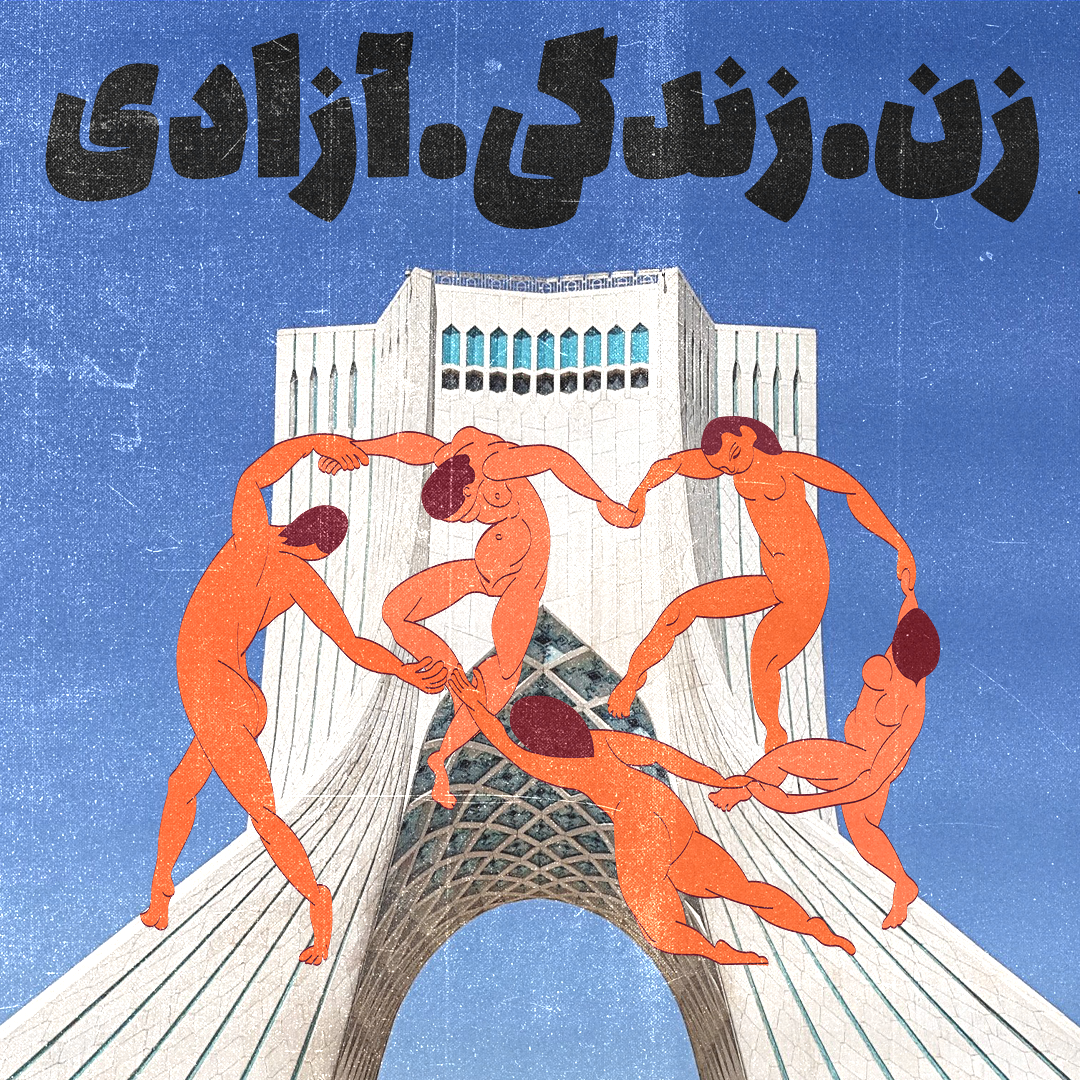

After all, it is true that the intention of the Norwegian Nobel Committee is explicit: through Narges Mohammadi it wanted to lend recognition to the entire protest movement that has marked Iran for the past year. This was said by Chair Berit Reiss-Andersen in making the announcement when she herself opened with the words “zan, zendegi, azadi” or woman, life, freedom. It is the slogan that has become the symbol of the protests that erupted after the death of young Mahsa Jina Amini in the custody of the “morality police” in September 2022. “The largest political protest movement since the 1979 Revolution,” noted the Nobel Committee through its chair, who added: Woman, Life, Freedom “effectively expresses the work and dedication of Narges Mohammadi.” Taghi Rahmani also wanted to emphasize that his wife’s Nobel is a recognition of her decades-long work but also for “all human rights activists fighting for change in Iran.”

From inside Iran other comments are seeping out, enthusiastic ones. One for all: “I cannot think of one person who deserves to receive the Nobel more than Narges Mohammadi…for her work in defense of human rights and political prisoners,” reads a post by Professor Sadegh Zibakalam (recently relieved of his duties at Tehran University because of his critical analyses of Iran’s political system). Some also point out with relief how important it is that this recognition has gone to those fighting inside Iran, rather than to the many figures from the diaspora who have presented themselves as leaders of a movement that has instead grown and matured inside the country.

Many activists in Iran, from Mohammadi’s generation and even younger, comment that in the past year a revolution has taken place in Iran. Or rather, a profound social and cultural revolution that has taken place in recent decades has become visible. The protests of the past year have mostly involved the young and very young, who find the Islamic regime’s norms too stringent. “But behind them are mothers and fathers who have worked to regain public space and win rights,” commented a noted feminist and sociologist recently.

Even the political establishment appears internally divided: a new law was announced last month tightening penalties for women who fail to comply with Islamic dress code; back in July it was announced that “moral guidance” teams (the so-called morality police) would be back in action. The reality is that very little is seen on the streets, while uncovered female heads are frequent and few dare to object. Nothing is taken for granted; repression is strong and so is censorship. Yet not even the most reactionary administration of the past forty years can stop an unstoppable cultural and social revolution, and a now widespread demand for freedom. Thanks in part to people like Narges Mohammadi, and so many activists alongside her, who have paved a way and continue to fight to keep it open.

Cover photo: a portrait of Narges Mmmadi, in Tehran, Iran, on February 4, 2021 (credits: Reihane Taravati / Middle East Images via AFP.)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.