There is a lot of ideology – i.e. politics at large – behind what we know, how we know, and what we do not know. Time, space, family, society, egoism, and the political world order we are born into are all major factors that impact our limited view of the things around us. Even in our scholarly studies, which are supposed to be “neutral” and “objective”, there is always the personal, and/or the political, whether we admit it or not. The most we can do to be balanced in our views is to control both the personal and the political, and only in this sense can we say we are “relatively neutral.” The fact that some Arab scholars, thinkers, and philosophers remain unknown in Western academia has to do with various factors, including the lack of financial means, human capital, and linguistic capacities, but externalization of critical thought from the “South” remains an important factor as well. If this situation persists, we will find ourselves some 200 or 500 years from now – at least those of us who study Arab and European intellectual histories – saying the same thing we say about classical Greek and Arabic intellectual exchanges: Was it genuine? Was it politically oriented? Was it profoundly intellectual? Was there originality in it? etc. If we fail to read the works of important intellectual figures now, we are just postponing the discussion to the distant future where the political dimension will be even more influential in dictating and influencing how such studies are carried out. Whatever we read and however we read it has some background, and when this is done decades and especially centuries afterwards, mostly the political motive emerges, mostly but not entirely, fortunately! When we invoke and invite the past we invoke and invite it for a purpose. The point I wish to make here is that ideas, however first theorized somewhere, cannot be replicated the same way elsewhere; that elsewhere has its own history and dynamics and influences towards newly arrived ideas. There is no purity in the world of ideas; no one idea remains pure once it moves outside its own context; small details make it something else; these small details have their originality which must be acknowledged. This statement has to do with the figure I would like to pay posthumous tribute to in the following piece.

A number of friends and colleagues from the Arab world as well as the US wrote to me to say that they did not know the Moroccan modernist philosopher Mohammed Sabila, after I had written a tribute to him since his death on 19 July 2021 because of complications due to Covid-19. A few of these colleagues work in Arab studies, and one of them knows the Moroccan intellectual context well enough, but still somehow missed Sabila who was in the public and academic spheres since the mid-1970s. I therefore felt an obligation to do the same this week, in memory of Mohamed Waqidi, an important figure in contemporary Arab and Moroccan thought.

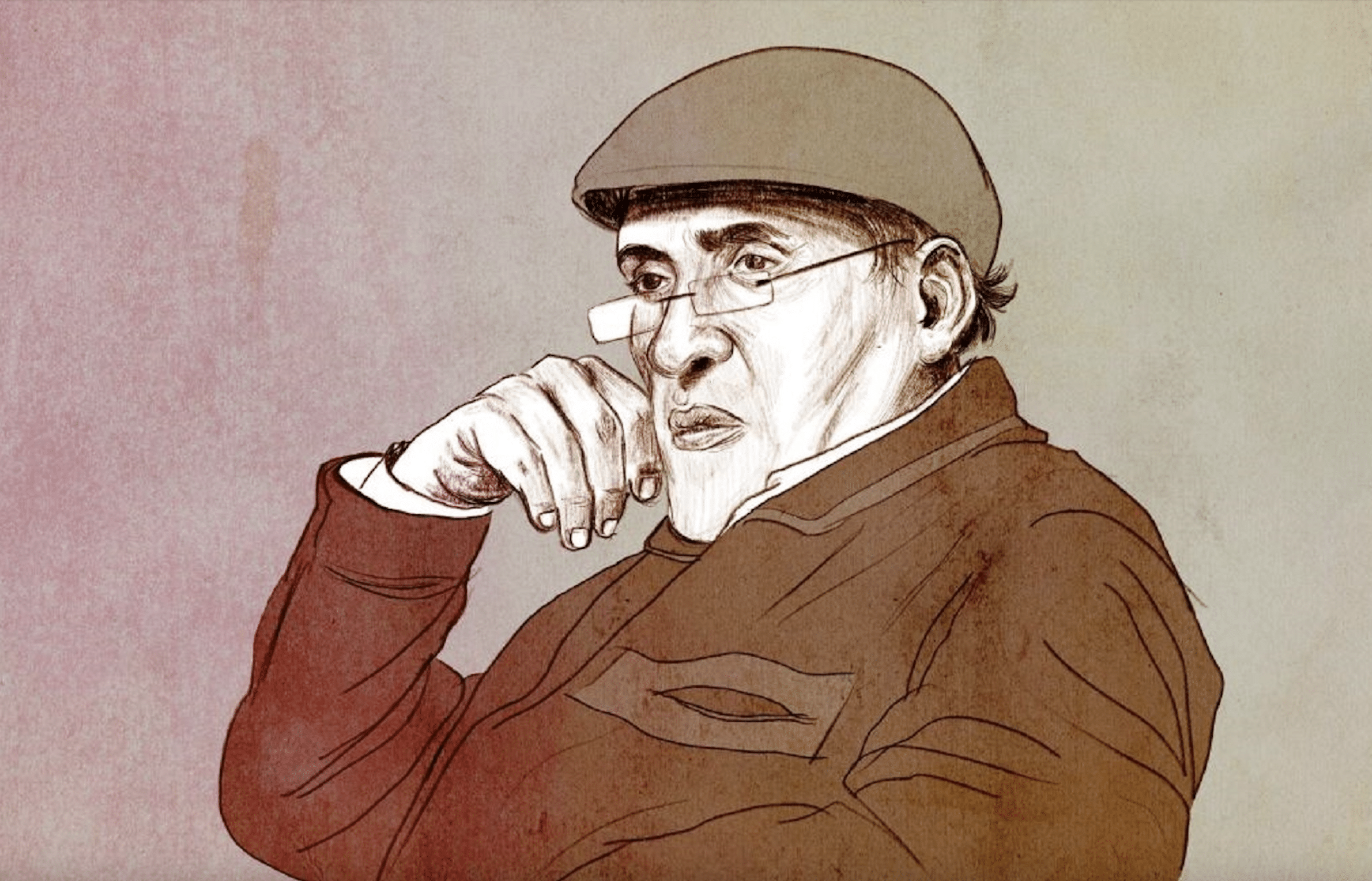

A critical epistemologist

Mohamed Waqidi (1946 – 07 August 2020, Rabat) died last year after a long illness that left him with loss of sight and impeded his ability to move. He was known in the Arab intellectual domain as the “epistemologist.” It is said that in a conference on democracy and human rights in the Arab world, the Egyptian philosopher Hasan Hanafi “jokingly” wondered about what an “epistemologist” would be doing in a conference on such a theme, to which Waqidi replied, in this occasion and in others, that he was first “an epistemologist citizen.” A few seminars were organized in homage to Waqidi, in his presence, for instance, in the Aziz Belal Center for Studies and Research in Casablanca in May 2014, and in the Forum for Cultures and Arts in Mohammedia in January 2015. He was mourned by scholars in various Arab newspapers in the Arab world and abroad.

Waqidi received his Degree of Higher Studies (DES) in philosophy from Mohammed V University in Rabat in 1979, where he had already been teaching Greek philosophy since 1975. He was previously a teacher of philosophy in high school, a period which afforded him a lot of opportunity to read, as he recounted at the abovementioned 2015 event held in his honor. Before his specialization in epistemology, the topic was taught by his teacher and colleague, Mohammed Abed al-Jabri (1935-2010), who produced two large scholastic tomes, An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (1976) and became references for generations afterward. They are still being re-published today; more than seven editions so far. Waqidi also taught the subject as a minor to some other departments, like the Arabic studies department, as the novelist and literary critic Said Yaqtin wrote in a 2020 tribute to his teacher. His peers Salem Yeffout and Abdessalam Benabdelali also wrote The Study of Epistemology in 1985, and Yeffout published Us and Science in 1995. A later generation of scholars, like Nasser Bouezzati and Abdessalam Benmaiss, also published on the philosophy of science. Waqidi, however, the most prominent scholar of epistemology in the Rabat school of philosophy. He moved from writing on scholastic epistemology, and from focusing on the philosophy of science, linked primarily to natural sciences and physics, to pushing its horizons into other fields of the humanities and social sciences, thus becoming a methodology for interpreting the dynamics and transformations, or not, of societies.

Waqidi became known first through his important work on the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard (1884-1962): Gaston Bachelard’s Philosophy of Knowledge (1980). From here on he understood what impacted knowledge production and its apparatuses, and consequently how these processes were reflected in society and its dynamics. In simple terms, Bachelard’s epistemology showed the scientific history of concepts and how they were concretized technically and pedagogically; it was a form of regionalization of scientific achievements and concepts instead of a form of general history of science. In other words, empiricism and rationalism are not two independent or dualistic rational methods of analyzing the object or the world; they are complementary. This epistemological perspective is not positivist, i.e., it does not consider that knowledge is based only on concrete experience and/or sensory experience as examined by reason and logic. Knowledge in Bachelard’s epistemology is Cartesian, rational, and dialectic, i.e., its validity or truth is based on reasoned argumentation. This reasoned argumentation does not exclude intuitive knowledge – which might have metaphysical or theological sources, among others – since it gives space to the work and influence of psychology. Bachelard’s historical epistemology aimed at showing that science and scientific achievements were not always linear, and follow general laws, and that there could be “epistemological obstacles” in science, obstacles that could occur due to possible human mental patterns. Consequently, this means that society cannot progress linearly, as the positivist August Comte argued. It is the role of epistemology, according to Bachelard, to examine these possible obstacles in the history of sciences, and by implication examine their socio-historical repercussions on human societies. That is what Waqidi took as his primary method and applied to the humanities, equipped with sociological and historical data, which Bachelard did not. This he did also as “a native scholar” from the global South.

Waqidi wrote The Humanities and Ideology (1983) to deconstruct the influence of ideology on the study of societies. Here, besides reading modern European transformations in their scientific context, he also brought in the socio-political context and its dynamics. From the European Renaissance period, through Enlightenment, until especially the late 19th and early 20th Century, reason and rationality triumphed. However, since the colonial period, until present, European reason, which is also applicable to human reason at large, no longer champions reason and rationality but power; – the reason of power over the power of reason, which is its current predicament, according to Waqidi. That is why he did not stop at the classical definitions of epistemology as the philosophy of science, or the study of methods of knowledge production. For him, epistemology should become a method of critical analysis of scientific epistemes as well as the epistemes of the power relations they engender. It is here that he emphasized the humanities as fields of experimentation for certain “scientific” achievements that became “ideological” weapons in the hands of the “powerful.” It is for this reason that he paid a lot of attention to sociological and historical data, since they reflect dynamics that exact sciences cannot reflect. If one champions only scientific data, then the powerful is always “right,” which is not the case. He gave European colonialism, Apartheid in South Africa (until mid-1990s), and the Israeli treatment of the Palestinians as examples of how the power of reason turned into the reason of power. For Waqidi, modern Western philosophy as a liberating means of modern human beings lost ground to power, might, exclusion, and neo-colonialism. To correct this situation, only scholars of the Third World, scholars from the South, can feel this predicament and are thus the only ones most able to critique and subvert it. He gave the example of how socio-anthropological and historical work developed by Moroccan scholars in the postcolonial period illustrates this path of knowledge production by natives, against the prevalent biases that dominated these fields during the French colonial period. In the case of Arab and Islamic societies, Waqidi said that unless the ideological premises on which Orientalism – in its biased form – change, the study and treatment of Arab and Islamic societies would remain the same. He called for “critical epistemology” (al-naqd al-ipistimology) as the way out of this scientific and ideological trap in which the world at large is in, including the Arab and Islamic worlds. It is here that Waqidi’s departure from the exact scientific premises of Bachelard are most clearly manifest; he tried to integrate history, sociology, and psychology in his overall work, to trace the scientific and debunk the ideological.

Waqidi also published the long and critical What Is Epistemology? (1983) in which he studied modern and contemporary epistemological paradigms as advanced by major scientists and philosophers like Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, as well as René Descartes, Immanuel Kant, August Comte, Henri Poincaré, Henri Bergeson, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russel, Robert Blanché, among others. Later in his career, he also worked on Jean Piaget’s epistemology and published Piaget’s Genetic Epistemology (2007), and Genetic Philosophy in the Philosophy of Science (2010). He tried to read Piaget as an applied rationalist, not only as a psychologist and child development theorist. Waqidi appreciated Piaget’s theory of knowledge production as being an outcome of both biological functions and external factors and thus retained a middle way between objective idealism and materialism. This connects Waqidi to Aziz Lahbabi’s philosophy of the “person” as well, as I will note below.

An epistemological citizen

Waqidi was a self-described “epistemological citizen.” His immersion in the study of modern physics and mathematics and philosophies of science did not distance him from the real world he lived in. At the end, his theoretical work aimed at understanding how the real world works. He engaged with contemporary Arab philosophy and wrote A Philosophical Exchange: A Study of Contemporary Arab Philosophy (1985), and On the Formation of Philosophical Theory: Studies in Contemporary Arab Philosophy (1990), among other contributions. His main argument here is that in the Arab world we cannot yet speak of an established tradition of philosophy but of philosophical beginnings, or re-beginnings from classical times. Since he knew how exact sciences impacted and still impact human thinking and social affairs and human governance systems, he concluded that the current Arab world, which is not productive of these modern scientific theories, cannot lead philosophical discussions, but can in most cases contribute to them critically and morally. This care for his socio-cultural milieu also gave birth to his co-authored work with the Tunisian reformist Hmida al-Nifer: Why Has the Arab Renaissance Failed? (2002). His criticism of global disequilibrium, and the disorientation of rationalism and championship of power, led to the publication of The Lost Equilibrium: Essays on World Order (2000).

More locally, Waqidi published on how to write a national history, and on the horizons of Morocco as a political entity. Just before his death, he published Mohammed Aziz Lahbabi: The Philosopher and the Man (2020). This book reflects the impact Lahbabi as the dean and professor of philosophy left on him both as an intellectual and as a human, as he did on most of the first generation of students of philosophy in the country. Lahbabi was the one who opened the Department of Philosophy at the first modern university in the country, Mohammed V University in Rabat. Lahbabi was immersed in classical and modern philosophy, Arab and European, and he was also a man of literature and poetry. Waqidi had previously dedicated already two books to him, Moroccan Studies and The Courage of the Philosophical Position, published in 1985 and 1999 respectively. It is highly possible that Lahbabi’s philosophical conception of the “person” as the outcome of accumulated external factors of relations, besides his philosophical and Sufi religiosity, impacted Waqidi who had Leftist leanings, according to Mohammed Mesbahi, the prominent scholar of Ibn Roshd/Averroes who moderated the homage seminar in Aziz Belal Center in Casablanca in 2014. In describing his colleague, he said that he retained good relations with different intellectual and political tendencies inside and outside the university, at a time when the Moroccan university in the 1960s and 1970s was heavily influenced and dominated by the Leftists. I personally only had one online exchange with Waqidi, when I heard of his publication on Lahbabi. We had intended to meet, but unfortunately he passed away before we could make true on our commitments.

Mohammed Hashas is currently a Research Fellow affiliate to Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO) in Berlin, and a non-Resident Research Fellow at the Center for Islam in the Contemporary World (CICW) in Shenandoah University in Virginia, USA. He teaches at Luiss University of Rome. His publications include The Idea of European Islam (2019), and Pluralism in Islamic Contexts (2021).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.