Democracy is under siege in the world, but in some countries, like Turkey, the threat is much more serious. And as the world’s attention has shifted away from Turkey’s major problems with press and freedom of speech in the past few years, the situation has continued to worsen. According to the latest Freedom House report published in March 2021, Turkey is rated as “not free”. In terms of the decline of liberties in the past ten years, the country is rated the second worst in the world (Freedom House 2021).

In order to understand the huge pressure on the media, consider the following: After the coup attempt in 2016, a State Of Emergency Rule was imposed for 2 years. A crackdown, not only on the media, but academia, the judiciary, civil groups, and politics, followed as well. In 2017, a referendum changed Turkey from parliamentary democracy to a so-called ‘Turkish Presidency’, essentially one-man rule with no rule of law. President Tayyip Erdoğan’s AKP allied with the ultra-nationalist MHP enacted a regime of rights violations and arbitrary rulings, crippling all institutions.

As politics became more polarized, the people of Turkey became increasingly polarised as well. Journalists and oppositional politicians, but also doctors, lawyers, academics, students, and any other voices of critical opposition, have become targets of the regime.

The “Dimensions of Polarization in Turkey” survey conducted by Bilgi University and published in November 2020 shows alarming political intolerance and a spiral of silence. For instance, participants responded that they would not share their political thoughts on social media. Only 18.8% of respondents would discuss judicial practices on Twitter, and only 29.2% would discuss them in school or at their workplace. Further, respondents expressed their preference for news sources close to their own political views, meaning they would not hear the ‘other side’ of the story (Turkuazlab 2020).

Methods to Suppress Journalists

After China, Turkey is still cited as the second jailer of journalists” by CPJ. Various data from different organisations present a confusing picture since the numbers vary widely, every association or union has different criteria and access to data, and it is hard to keep track of journalists’ arrests and releases. Some organisations count media workers in addition to journalists. Some categorise ‘terror charges’, such as those involving supposed Gulenist and PKK-related cases, individually. It is important to note that almost all journalists are jailed on terror charges. This false narrative supports the regime’s claim that “journalists are not jailed, terrorists and criminals are”.

The most extreme form is imprisonement, but there are other methods to hamper press freedom. Journalists are constantly investigated, tried, targeted, and attacked. Terror, conspiracy against the government, espionage, as well as ‘insulting the president’ are common charges the government uses to suppress journalists. Press in Arrest, an EU-funded database for monitoring and documenting press trials in Turkey, clarifies the Constitutional rights as well as the arbitrary Penal Code and Terror Laws in their January 2021 report, “Why and how is journalism a crime.” According to the report, three hundred and fifty-three journalists have been prosecuted in the last two and a half years.

In 2020, there were 137 press-related trials, and two hundred and five journalists were tried. Turkish Courts gave twelve counts of aggravated life sentences, totaling up to 3182 years of prison sentences in 2020. A total of 1,869,000 Turkish lira was fined. There are 233 ongoing cases against journalists. 73 journalists were on probation with strict judicial oversight, meaning that the passports of the journalists were confiscated.

House arrest is an increasingly widespread punishment. Journalists and citizens are also regularly charged with violating the law against insulting the president and his family (Press In Arrest). According to Balkan Insight, a website covering Southern and Eastern Europe, between the years 2014 and 2019, 128,872 probes were launched into supposed insults against Erdoğan. There are currently 27,717 criminal cases and the number is climbing. In total, 9,556 people were charged, among them nine hundred and three minors aged between 12-17, who had to stand trial. Digital targeting and attacks against Turkish and Kurdish journalists are so common that those affected often don’t bother reporting them. Physical attacks against journalists are on the rise as well: In 2020, sixty-five journalists were attacked (Turkish Journalists Association’s Freedom of Press Report, 3 May 2020).

Censorship and Financial Fines

The few left-leaning, oppositional TV channels and newspapers are being crushed with fines and broadcast and advertising bans, making it more and more difficult for them to survive. The agency responsible for distributing the state advertisement budget, the Public Advertising Agency (BIK), has imposed ad bans on independent newspapers, such as Birgün and Evrensel (IPI Media 2020). The Radio and TV Supreme Council (RTÜK) issued sixty-seven fines in 2020. One TV channel was shut down and 49 broadcast bans were applied. (Turkish Journalists Association 2020) Four major oppositional TV channels, FOXTV, HALK, TELE1 and KRT, were fined up to eleven million Turkish lira. (Bianet 2020) Media pluralism is nonexistent in the mainstream as the regime owns and directly controls ninety percent of all media. Even as pluralistic journalism shifts to online platforms, thousands of websites and news links are arbitrarily blocked.

The new social media ban poses another grave threat to independent journalism. Platforms like Twitter that didn’t appoint a representative and agree to remove content at the request of the authorities are now banned from collecting ad revenues. Further consequences came since May 2021 when bandwidths have started to be cut down if they don’t comply (Euronews 2021).

The Notorious Press Card

Turkish Press cards are issued by the Directorate of Communications (CİB). In order to obtain a press card, one must be a complying journalist. However in February 2020, more than six hundred press cards were revoked (Duvar, December 2020). International reporters and agencies are forced to comply with the governments’ requests as well. In order to get accreditation and work in the country, foreign correspondents need to maintain good relations with the regime.

Press cards are used as a tool to discriminate and paralyse all critical journalists. Aydın Engin’s press card, a veteran journalist for more than 60 years, was provoked without a notice. Reporters without a press card covering protests are blocked and detained by the police, even if they hold an international press cards such as IPI, IPJ.

In some cases, a journalist can be charged with ‘terrorism’ if he or she does not hold a press card. In September 2020, the Mesopotamia News Agency (MA) broke the news that two Kurdish villagers living in the northeastern province of Van. One of them died after a few days (Duvar November 2020).

The MA followed up on the torture case. Shortly thereafter, four Kurdish journalists including two MA reporters, Cemil Uğur and Adnan Bilen, were arrested. The Court detained them on the grounds that they were reporting on social events opposing the government, and that they didn’t have a press card, concluding they were unauthorised to work as journalists. Four journalists were imprisoned for 6 months. Only after their first hearing they were released on bail.

Sadly, unions and associations are not unified in their responses, as politics has affected them as well. Mainstream media is greatly controlled by the regime, partisanship and censorship is common. Misinformation spreads easily and has great impact on politics.

Independent journalists and media outlets are the only hope to stand up for press freedom (IPI).

Sources

Freedeom House https://freedomhouse.org/country/turkey/freedom-world/2020

Turkuazlab https://www.turkuazlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Survey_Key_Findings.pdf)

Reporters Without Borders https://rsf.org/en/taxonomy/term/145

Turkish Journalists Union https://tgs.org.tr/cezaevindeki-gazeteciler/

Platform For Independent Journalists http://platform24.org/en/articles/800/freedom-of-expression-and-the-press-in-turkey—278

Committee to Protect Journalists https://cpj.org/europe/turkey/

Press in Arrest http://pressinarrest.com/rapor/press-arrest-november-2020-press-freedom-report/

Press in Arrest http://pressinarrest.com/rapor/press-arrest-november-2020-press-freedom-report/

Press in Arrest http://pressinarrest.com/rapor/major-crime-turkey-journalism/

Press in Arrest https://balkaninsight.com/2021/01/15/investigation-highlights-spike-in-cases-of-insulting-turkish-president/

https://www.evrensel.net/haber/403795/basin-ozgurlugu-raporunu-aciklayan-tgs-gazeteciler-kalemlerini-ozgurce-kullanamiyor

duvaR. https://www.duvarenglish.com/who-does-the-turkish-govt-consider-a-journalist-article-55567

duvaR. https://www.duvarenglish.com/columns/2020/11/05/silence-continues-on-the-helicopter-torture-case)

IPI https://freeturkeyjournalists.ipi.media/turkey-digital-media-report/

Istanbul based journalist Mehveş Evin is a writer, freelancer and podcast host. Starting her career in 1993, she worked as a reporter, editor, managing editor, digital news editor and column writer in Turkish mainstream media until 2015. Evin covers press freedom, politics, human rights, environmental and women’s issues. Her first book “From A to Z: How did we get here?” (Kara Karga Publications) which focuses mainly on social and political challenges between 2002-2018 was published in August 2018. Evin regularly writes for artigercek.com, duvarenglish.com and hosts a podcast show for kisadalga.net. She has a bachelor’s degree in Psychological Counseling (Bogazici University, 1993) and an e-MBA degree (Bilgi University, 2006).

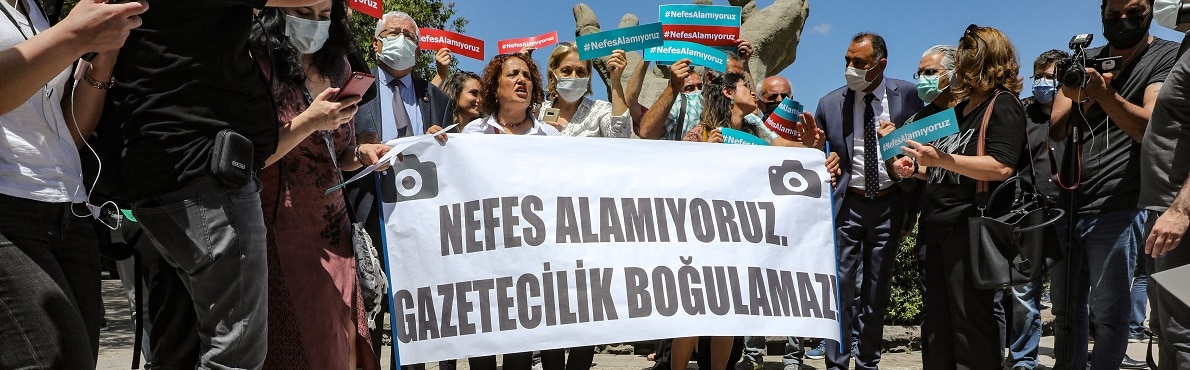

Cover Photo: People stand behind a banner reading in Turkish “We can’t breathe. Journalism cannot be drowned!” during a rally outside the offices of the Governor of Ankara – June 29, 2021 (Adem ALTAN / AFP).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.