“The Congo has continuously constituted a textbook example of the resource-death equation historian and political scientist Achille Mbembe calls necropolitics,” writes anthropology and sociology professor Jeffrey W. Mantz in a 2008 article, “Blood Diamonds of the Digital Age: Coltan and the Eastern Congo.” Achille Mbembe, coining the term in a 2003 article, as well as in his book Necropolitics (2016), describes the neologism as “a unique form of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead” or “the power to manufacture an entire crowd of people who specifically live at the edge of life, or even on its outer edge – people for whom living means continually standing up to death.”

A close look at how, today, essential minerals for the growing global market for portable electronic devices and rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles are mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo, reveals an economic structure one can call necro-mining.

In Cobalt Red: How the blood of the Congo powers our lives published in January of this year Siddharth Kara, activist and expert on modern day slavery and child labor, reveals the dark side of the digital and green revolution with harrowing accounts of the lives of artisanal miners, from diggers to washers and transporters, in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Copper Belt, Katanga and Lualaba provinces. Claude, a miner, tells Kara: the Kasulo mine, a neighborhood of Kolwezi, “is a cemetery;” others say: “We work in our graves”, “if we do not dig, we do not eat.”

Often the miners, when digging with their bare hands and no safety equipment in underground tunnels are injured or killed as these tunnels collapse. “Kasulo is also the face of everything that is wrong with the global economy. Nothing matters here but the resource; people and environment are disposable. Everyone who digs in Kasulo lives in mortal fear of being buried alive,” Kara writes.

Congo’s resources: at what price?

Cobalt, a rare silvery metal, is an essential component to almost every lithium-ion rechargeable battery made today – batteries used for iPhones, tablets, and electric vehicles.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has the largest cobalt reserves in the world, estimated as of 2022 at some four million metric tons, accounting for nearly half of the world’s reserves of the metal. In 2021, 72 percent of mined cobalt came from this area in Congo. The region is nicknamed the “Saudi Arabia of cobalt” for its high-quality cobalt.

All cobalt sourced from the DRC is, according to Kara who recently traveled extensively in the region, tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, as well as incalculable environmental harm. There is currently zero accountability at the bottom of this supply chain.

Demand for this mineral is expected to increase immensely as the European Union envisions phasing out new vehicles with thermal or hybrid engines by 2035, to be replaced with electric vehicles.

In a recent ARTE documentary film by Arnaud Zajtman and Quentin Noirfalisse “Cobalt, the other side of the electric dream”, we see the sub-human working conditions of the artisanal miners and their co-workers in Katanga and Lualaba provinces, as well as the extreme pollution that is however caused mainly by large scale industrial mining also present in the area. “The entire region risks becoming an ecological and toxicological scandal,” director of the department of toxicology and the environment at the University of Lubumbashi, Célestine Banza, says in the film.

Red Cobalt and Cobalt, the other side of the electric dream focus on cobalt mined in an area of the country which is not at war, and thus they do not cover the so-called conflict minerals (tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold), which are mined in war-torn eastern Congo and are just as essential for the digital and green revolution. For example, in a smartphone tin is used to solder metal components together, tungsten is in the components that make a phone vibrate, gold is used in circuit board connectors and columbite-tantalite, known popularly in Africa as coltan – a dense silicate from which one gets tantalum – is essential for the production of mobile phones, video game consoles, and laptops. Because it is dense, highly efficient in retaining heat, and resistant to wear, industrial engineers and others in the electronics manufacturing industry have sometimes referred to it as the “holy grail” in digital electronics.

Proxy international wars disguised as civil wars

Although Mobutu Sese Seko’s Congo (1965-1997), then known as Zaire, was a corrupt dictatorial regime, the mining industry had been nationalized in the Katanga region and partially nationalized in the East under his rule and was thus a major revenue source for the country’s economy. Working conditions and salaries for the miners were far better than today.

Historically, the Rwandan and Ugandan occupation of eastern DRC via proxy rebellions began in 1996. A financial conglomerate of predominantly Canadian and American companies known as American Mineral Fields Inc (AMFI) financed and armed a sham rebellion known as the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL) which invaded Zaire. The AFDL was presented to the world as a liberation movement. In reality the AFDL was created by the then Rwandan Vice President Paul Kagame and the Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni and placed a Congolese former rebel, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, at its head to give it a Congolese façade. Kabila hastily raised an army composed mainly of child soldiers and a few disillusioned Mobutists, but it was mainly the Ugandan and Rwandan armies that would lead the fight. In just seven months they managed to arrive in the capital Kinshasa and overthrow Mobutu Sese Seko.

Colette Braeckman in a 2006 article published by the Congolese League to fight against Corruption (LICOCO) calls this period “the third looting” in Congolese history, namely the looting of the country’s very infrastructure by private Western companies. Historian and currently Permanent Representative of the DRC to the United Nations, Georges Nzongola-Ntalanja demonstrated in his book The Congo from Leopold to Kabila: A People’s History, how the notion of a civil war was manufactured by Rwanda, Uganda, and their promoters as a pretext for the 1996 and 1998 invasions, whose main goal was the occupation of eastern Congo, a region they still occupy to this day.

A detailed account of mining companies such as Lundin Group, Banro, Mindev, Barrick Gold, South Atlantic Resources and Anvil Mining, who fuelled this war, can be found in Patrick Mbeko’s Canada and the Tutsi Power of Rwanda: Two Decades of Criminal Complicity in Central Africa, written in 2014. “Noir Canada” by Alain Deneault published in 2008 also documents the role of Canadian based mining companies in the war, was attacked in 2008 by Barrick Gold which filed a 6 million dollar lawsuit against its authors and their publishing house for defamation, and Banro also filed a SLAP (Strategic lawsuit against public participation) against them in an intimidation tactic . The documentary film Silence is Gold follows Alain Deneault and the publishing house Ecosociété‘s struggle to defend themselves from the lawsuit.

The illegality of these mining contracts was denounced in the first report of the Panel of Experts on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of DR Congo, a group commissioned by the United Nations Security Council to investigate trade agreements signed in eastern DRC during the war. Over the years these biannual reports have often been ignored, censored, watered down and even suppressed.

The downplaying of the direct link between conflict minerals and the proxy international war in eastern DRC in books such as The War That Doesn’t Say Its Name: The Unending Conflict in tghe Cono, by Jason K. Streans, thus do a huge disservice to attempts at understanding necro-mining.

The occupation of eastern DR Congo by proxy Rwandan militias who simply change acronyms – from RCD-Goma, to CNDP or today’s M23 or ADF – has forced civilians to organize in self-defense groups to protect their territory. These foreign proxy militias terrorize the local population and also destroy the possibility of other viable activities such as local agricultural production. Today over 10 million people have been killed in this region since 1996 and there are 6 million internally displaced civilians.

The impact of “Obama’s Law”

An excellent recent documentary film that provides a rare insight into both the lives of ordinary miners in eastern DRC, as well as the glaringly disconnected activism in the West, is “We will win peace” by Seth Chase. Seth Chase not only portrays the subhuman conditions that miners in the DRC face, but also shows how Section 1502 of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (2010), known formally as the Conflict Minerals Law, or what Africans colloquially refer to as Obama’s Law (which enforced the traceability of conflict minerals), is an example of what he calls “humanitarian porn”. It has the opposite effect of its intended purpose, as the artisanal miners are pushed even further into a life of misery.

“A traceability of weapons and their manufactures would be a more viable way forward than the current schemes,” head of certification of the country’s Ministry of Mines Thierry Sikumbili says in the film. He also underlines that the DRC was not consulted when Dodd-Frank was passed, a disturbing detail in itself. More disconcerting, the film shows how the implementation of “Obama’s law” forced miners to form self-defense groups to protect their area against the Rwandan proxy militias which instead were allowed to operate freely, while the miners’ work was classified as illegal.

As prices and production in the Kivus and Maniema decreased by between 80 percent and 90 percent respectively following President Joseph Kabila’s embargo on the export of conflict minerals from September 9, 2010 to March 10, 2011, it left people with few opportunities as up to two million jobs were affected. Many eventually joined the very militias that the law’s passing was intended to quash.

In 2009, President Joseph Kabila legitimized a peace process that ended up weakening the country’s national army, as the peace accord called for integrating (via a system called brassage) of former foreign rebels into the national army. Kabila’s mining ban thus also allowed the Congolese national army (FARDC) – or rather former rebel battalions serving in the same areas as during the 1998-2003 war – to consolidate control over some previously non-militarized mines (e.g., at Kamituga, South Kivu Province), thus crowding out the local population. In the absence of government military protection, civilians in remote areas formed self-defense groups to fight forced evictions.

A 2018 study by University of Antwerp researchers Nik Stoop,Marijke Verpoorten, and Peter van der Windt, More legislation, more violence? The impact of Dodd-Frank in the DRC building on a dataset of mining sites and extended over three years (2013–2015) showed that the policy backfired in the long run, especially in areas home to gold mines. For territories with an average number of gold mines, the introduction of Dodd-Frank increased the incidence of battles by 44 percent; looting by 51 percent and violence against civilians by 28 percent, compared to pre-Dodd Frank averages. The 2011 Final Report of the UN Group of Experts on DR Congo notes that the de facto ban has led to an increase in conflict mineral smuggling via Rwanda.

According to Professor Jeffrey W. Matnz, the international aid community that intervenes in the DRC through regulatory practices such as Dodd-Frank is a form of fetishism, which manifests not only through the commodity supply chain itself, but through the promotion of discourses that serve to legitimize political and economic imbalances, thus suppressing alternatives to necro-mining.

Mantz points out the sheer irony of reporting on these exploitative production and circulation systems in Africa, engineered by affluent nations and fueled by consumer demands: “A Google search of ‘Play Station 3 Violence’ yields nearly 2 million hits; most of the initial pages are devoted to news stories covering the November 2006 release of the gaming device, where a short supply (a mere 400,000 units) led to conflicts, including shootings at Best Buy stores around the US.”

(Im)possible solutions to never ending exploitation

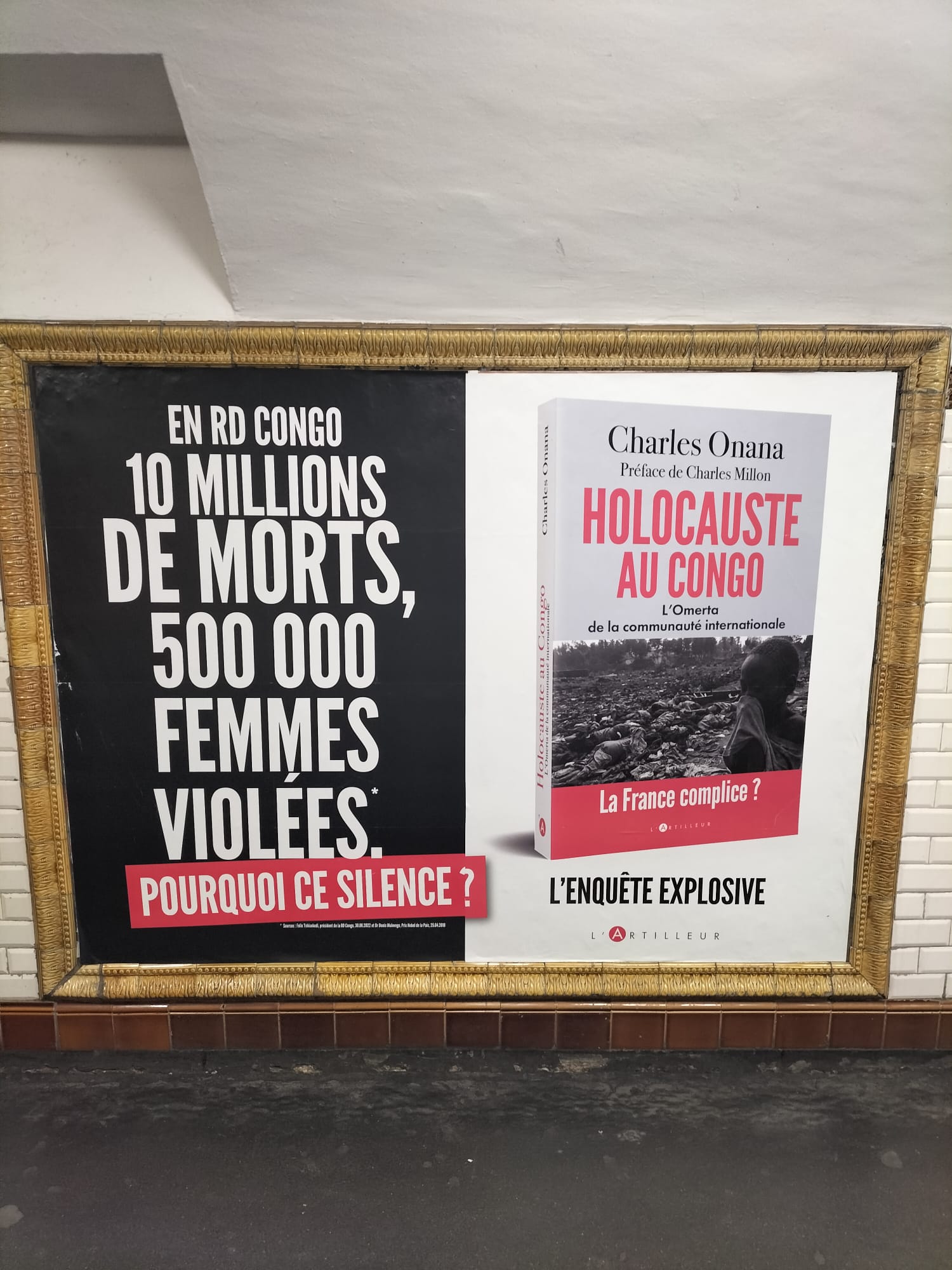

An ahistorical account of this extremely problematic state of affairs without taking into consideration the geopolitics at play, misses the possibility of finding viable solutions forward. A forthcoming book Holocauste au Congo, L’omerta de la comunité internationale (Holocaust in the Congo, The omertà of the international community) by Great Lakes expert and scholar Charles Onana reconstructs – through the use of a wide array of archival documents ranging from US Presidential records, the Pentagon, the European Union to the United Nations – how the intentional occupation of this region is in place to loot its natural resources.

In a 2020 article, “Would You Fight? We Asked Aggrieved Artisanal Miners in Eastern Congo”, Nik Stoop and Marijke Verpoorten address crucial questions such as what is the best option for the local population’s well-being, artisanal mining in its mechanized form or large-scale mining? Since large–scale mining is an enclave economy which crushes the local economy; tends towards monopolies; creates enormous environmental damage that hinders agricultural production in the regions it occupies; crowds out artisanal mining when production is initiated, leading to more violence against civilians; is a capital-intensive production mode which creates little employment and even deliberately hinders mechanized forms of small-scale mining, one can only wonder why most humanitarian work has focused on artisanal mining.

Kara in Red Cobalt reminds us of the centuries-long exploitation of the DRC that accompanied various western developments: “Ivory for piano keys, crucifixes, false teeth, and carvings (1880s), rubber for car and bicycle tires (1890s), palm oil for soap (1900s), copper, tin, zinc, silver, and nickel for industrialization (1910), diamonds and gold for riches (always), uranium for nuclear bombs (1945), tantalum and tungsten for microprocessors (2000s), and cobalt for rechargeable batteries (2012).” The Congo was colonially constructed as a space where profitability could be maximized through immense violence and immiseration and this logic, Owen Dowling reminds us, persists into ‘post-colonial’ capitalism through the continued devaluation of Congolese labor.

Asian, Middle Eastern and Turkish Studies Professor Isa Blumi in Destroying Yemen writes about the devastating consequences of ignoring the underlying ambition of those representing capital to keep a country servile to the needs of certain regional and global interests: “By all means necessary” hums the engine in Wall Street as yet another indigenous community in some far-off jungle or mountain top gets wiped out for the cobalt that lies underneath.” Without a holistic analytical approach, no way forward for the Congolese population can be seen in this ongoing predatory extractivism, super exploitation that has caused what in 2015 Noam Chomsky and Andre Vltchek called a super genocide and Charles Onana today calls Congo’s Holocaust.

Cover Photo: a child and a woman break rocks extracted from a cobalt mine at a copper quarry and cobalt pit in Lubumbashi on May 23, 2016 (Photo by Junior Kannah/Afp)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.