Russia’s invasion of Ukraine complicated China’s foreign policy greatly. Unfettered access to raw materials, fuel, markets, and technology is crucial to China’s sustained development. Continued hegemonic dominance of global capitalism and post-Bretton Woods international organisations by the US, the EU and NATO is a problem. Economic interdependence and multipolarity are solutions. China needs allies or fellow travellers to offset this hegemony and redefine the international order.

The war in Ukraine has mobilised NATO countries against Russia and NATO is trying to garner backing from the rest of the world based on the war, but the rest of the world is baulking at the prospect because the interests of developing countries do not coincide with the ones of NATO countries. The interruption of supply chains and disruptions to the global market caused by direct consequences of the war and by economic sanctions against Russia promoted by NATO countries hinder their development. Diplomacy, not war, is what China wants, as does India, as do many more countries, leading to a stabilisation of world markets and supply chains.

China cannot support Russia’s war. Nor can it line up behind NATO’s leadership. The elimination of Russia as a counterweight to NATO hegemony would weaken the prospects of multipolarity. So, China could not countenance a humiliating Russian defeat either. Vladimir Putin has created a very uncomfortable dilemma for Xi Jinping. Yevgeny Prigozhin’s short-lived mutiny threatened to be another complication.

Putin’s invasion put Russia’s reliability as a partner in off-setting NATO’s hegemony in doubt and Prigozhin’s mutiny put Putin’s reliable hold on Russian stability in doubt. Xi has let Putin know in no uncertain terms that China cannot accept Russian nuclear recklessness. China seeks a possible role as peacemaker, but the standoff between Ukraine and Russia is intransigent. One question arising is whether Prigozhin’s mutiny might have any implications for China.

Deng Xiaoping believed that Mikhail Gorbachev’s fundamental error was the attempt to introduce political reform before economic reform. The collapse of the USSR led to what Marshall I. Goldman called the “piratization” of Russia, and a spiral of political and economic chaos that irretrievably weakened the former counterweight to NATO, exposing China to western countermeasures designed to contain growth and influence. Deng promoted economic reform while maintaining strict political control. Xi follows the same strategy, trying to regain even more political control over stability.

The Party’s main strategic goal is to raise the collective standard of living, but to do so, it must have power. As a result, its main tactical goal is maintaining itself in power. This means that “stability preservation” (维护稳定 weihu wending) is the guiding principle. Mao Zedong famously said “from the barrel of a gun comes political power”. More importantly, he added, “the Party points the gun” (党指挥枪 dang zhihui qiang), the gun must not point at the party. Mao’s dictum alluded to the millennial division in traditional Chinese political philosophy between the warriors in the ruling class who based power on military strength (武 wu or hard power) and the Mandarins, who based power on knowledge and information (文 wen or soft power).

This brings us to the crux of the dilemma that Prigozhin’s mutiny might mean for China. Could Xi or the Party fall victim to a mutiny? For the short term, at least, that seems highly unlikely. Xi has carefully filled the highest ranks with loyalists. He presides over the Central Military Commission. Deng withstood the radical Maoist attempts to purge him thanks to his allies in the military. Xi learned this lesson well.

It was the radical Maoists who gave the Party its greatest scare of a mutiny in the Lin Biao incident in 1971. Lin Biao had been designated to be Mao’s successor. A botched mutiny that may have been promoted by his son to accelerate the alternation of power led to Lin’s death in a plane crash over Mongolia. There is much evidence to suggest that there was resistance among high-ranking officers of the Peoples Liberation Army in the capital area to the use of military force to quell civilian demonstrations in Beijing in 1989, leading eventually to the use of military officers and units from much further away. These would be the best-known cases of mutiny since the 1949 revolution. If there have been more, they have been kept well-hidden. The Party has kept control of the gun.

Of course, Prigozhin’s mutiny did not come from the regular army. The Wagner group are mercenaries. Both the US, in Afghanistan and Iraq, and Russia, have come to rely more and more on Private Military Companies (PMC) to supplement the regular armed forces. The loyalty of mercenaries may be put in doubt. China does not have any PMCs. It does have Private Security Companies (PSC) to provide protection for large-scale Belt and Road Initiative projects, among other duties. But the Party-State maintains full control over its armed forces.

China’s strategy to take centre stage in world affairs did not include planning for a world war. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and NATO’s response, have raised that unwanted prospect. Putin’s erratic foreign policy weakens China’s careful promotion of a multipolar world order because it has brought NATO out of the doldrums, and strengthened the hand of the US in trying to contain China by encouraging band wagoning among China’s neighbours, who want to hedge their bets between economic interdependence on China and US guarantees of security against China.

The response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also raises questions about how far China could go regarding reunification with Taiwan. The EU has not blindly followed the US lead on decoupling with China, but it has begun a strategy of de-risking, of relying less on China for strategic resources. Putin’s strategic gamble has created many strategic headaches for China. All in all, however, China’s stability seems more secure than Putin’s.

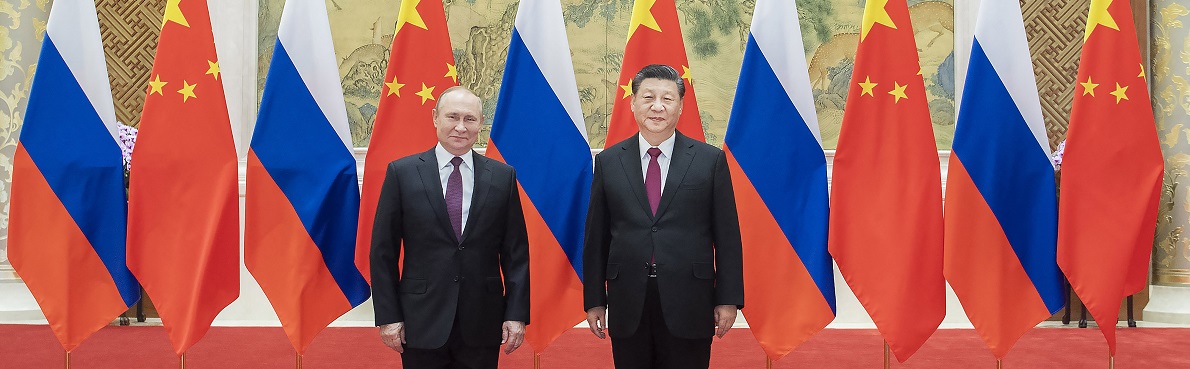

Cover photo: Chinese President Xi Jinping with Russian President Vladimir Putin at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing, capital of China, Feb. 4, 2022 (photo by Li Tao/Xinhua via AFP.)