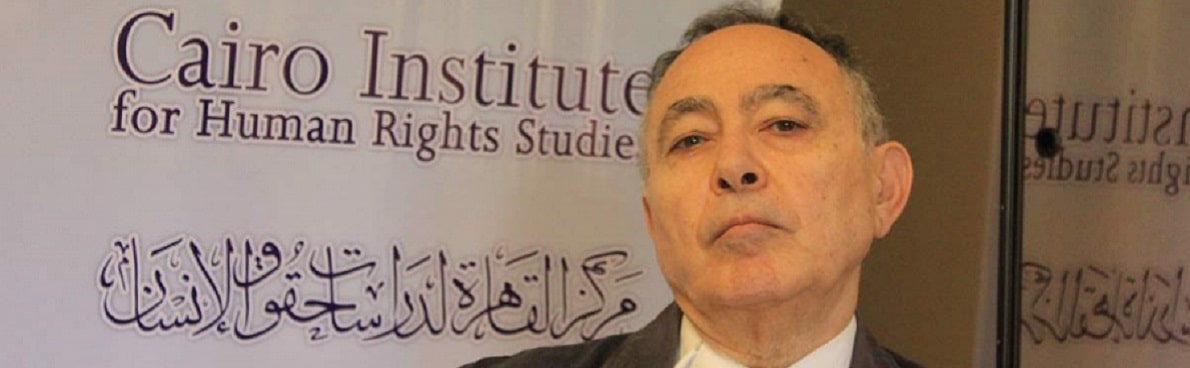

Bahey Eldin Hassan speaks from his place of self-exile, the one he chose when he felt the urgent need to protect himself. Six years have gone by since he fled Egypt, years marked by death threats (even in the press), the confiscation of his family wealth, the transferral of his NGO’s headquarters (one of the most important in the region) and the addition of his name on the list of those not welcome at Cairo airport. There was also a court case he started but that was never completed by the Egyptian judiciary against a television host who, during a live programme, called for him to be assassinated using poison following the “Russian method”. Two court cases were eventually brought against him, formally different but overlapping, that both ended with a sentence passed against him; the last one on August 25th sentenced him in absentia to 15 years in prison.

“For decades judiciary independence in Egypt has been one of the objectives I have devoted my life to. For all these years I have joined forces with very principled judges working to achieve the same objective. I invite them to continue their battle to be free from state security’s domination over the way justice works. Only an independent judiciary will eradicate repression in Egypt,” says Bahey Eldin Hassan just a few hours after hearing how many years he would have to spend in prison should he decide to return to his homeland even for just for a few days. Few words that do not address the essence of the absurd sentence passed for case number 5370, dated 2020, against him, but that comment instead the even more absurd merging and superimposition of power in Egypt, a country that ten years after the Tahrir Square revolution shrugs at the division between the legislative, executive and judiciary branches and, once again governed by the military, must do with a judiciary ruled as in the past by the executive branch. Such power is in the hands of the army that dominates all others. The sentence was in fact passed by a court that addresses issues linked to both real and cyber terrorism. According to a recent law involving cybercrimes[1] – a rule added to a broader draconian law on the media – Bahey Eldin Hassan was accused of having insulted the judicial system and of having spread fake news especially through social media, but also by attending international conferences, some also recently hosted recently in Italy, where a year ago an interview with Il Manifesto had sparked the rage of the Egyptian media.

This was an accusation that various international organisations – first among them Amnesty International – described as unfair and part of a vaster and worrying crack down implemented by the regime as far as human rights defenders were concerned, using popular slogans such as the war on fake news and terrorism. In Egypt the word terrorism is used not only to describe the increasingly dangerous militias in the Sinai and along the border with Libya, but also those who oppose the military regime.

According to the NGO led by Bahey Eldin Hassan, the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, the sentence passed for case number 5370 is set within the context of a wider campaign for “state security” that has been ongoing for at least six years about which Bahey Eldin Hassan had expressed his criticism also in the New York Times three years ago. It is a campaign – reports the NGO – that is expressed using “intimidation and vengeance targeting Egyptian rights defenders both inside and outside the country, with the goal of deterring them from exposing serious human rights crimes.” Bahey’s biography itself is marked by moments of threats and vengeance as proved in another recent court case in which, once again in absentia, he was sentenced to three years in prison and 20,000 Egyptian Lire fine (about 2,000 euros) for having libelled the judiciary in a tweet (case 5530 dated 2019).The allegations were similar to those that resulted in the recent, even harsher sentence that was the result of investigations carried out by the same public prosecutor who had decided to stop inquiries concerning charges made by Bahey against the television host who had incited his murder.

A beacon for human rights

Attacking the elderly Bahey means attacking a pillar of the spread of a human rights culture throughout the entire region. He can in fact most certainly be considered one of the fathers of Egyptian human rights activists and defenders, many of whom attended courses he organised at the Cairo Institute already long before the Tahrir Square revolution. Bahey – who in addition to his passion for human rights has an equally powerful one for art and culture – assumed a public position at the end of the Eighties when he became a member of the commission for freedom of the press within the journalists’ trade union. A few years later he joined pan-Arabic organisations devoted to the defence of human rights, to then eventually create the Cairo Institute, a beacon in the defence of human rights with a light shining well beyond the country of the River Nile.

In the 1990s it was already clear that its activity was disliked by the regime and the organisation’s board members were arrested and tortured. Ever since the foundation of his institute, Bahey was therefore obliged to fight not only for the NGO’s survival but also for his own safety. He himself told me about this in 2014 while I took notes about his flight which soon became self-exile, today almost irreversible. “For me the worst period has been the most recent one, following the Army’s return to power, with everything becoming extremely more complicated and dangerous” he explained when deciding to take refuge in a safe location thousands of mile from Cairo.

He is one of the oldest human rights defenders to choose exile. Like him, hundreds of young and more elderly people, lay and Islamists, intellectuals and doctors, professors, trade unionists, artists and journalists have ended up leaving Egypt to flee the repression that now has the country in its grip. This is a new diaspora with different capitals, as many places as the political currents involved, and the different aspects, as well as in some cases differing political agendas. It is a new phenomenon that personally attracted my attention already in 2014, when I started to follow a series of stories about journeys that were as fast as they were painful and then merged into what appeared to me as a new “Flight from Egypt” [Fuga dall’Egitto] (Infinito Edizioni), a book – that also includes Bahey’s story – and that in the end became an investigation of the post-coup diaspora.

It is a story that over time also attracted the attention of academics and researchers, as seen in the essay published in 2019 for the Carnegie Institute by Michelle Dunne and Amr Hamzawy, he too having fled Cairo due to events similar to those experienced by Bahey Eldin Hassan and that effectively obliged him to abandon one of his university chairs. Egypt’s political exiles: going anywhere but home is the first academic acknowledgement of a subject about which many young researchers are curious, as proven also by the thesis by Mostafa Elsayed Hussin presented at the Norwegian University of Munin. This is an empiric and ethnographic essay that analyses two of Europe’s communities most popular with Egyptian exiles, Paris and Berlin, narrating how these specific diasporic communities try and make sense of their daily lives, in many cases without giving up the resistance activities that obliged them to flee. It is a study that reveals something already spoken of for many years, hence how even the simple renewal of a passport has now become a complex mission for those who – far from Cairo – continue to sing out of tune.

[1] TIMEP, Cybercrime law, December 19th, 2018, https://timep.org/reports-briefings/cybercrime-law-brief/.

Cover Photo: Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies

Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook. And share our contents.

If you liked our analysis, stories, videos, dossier, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).