While the mainstream media under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government has become a one-sided propaganda machine, several alternative media initiatives have started to be established in Turkey. Turkey is a country where hundreds of opposition newspapers, TV channels, radio stations, and websites have been closed down under the State of Emergency, and hundreds of journalists have been imprisoned with thousands more incriminated by the state. For these reasons, it has become important to discuss whether the alternative media can be a solution to these problems or not.

There is a history of alternative media in Turkey from the Ottomans until today, and it is possible to discuss alternative media examples in different eras. However, this text will focus on the post-AKP alternative media. In particular, it will look at the period after 2007, when the AKP became increasingly authoritarian and changed the state of mainstream media both economically and culturally with the motto: one party, one leader, one media.

After 2007, as the AKP consolidated its power to rule as a single party, the pressure on the opposition media increased. This pressure was applied in several ways: economic pressure and tax penalties on firmly opposed newspaper bosses, pressure on media companies to fire dissident columnists, and pressure in the form of jail time for journalists who wrote about the government’s dirty businesses. This situation became alarming after the Gezi Park protests in 2013, worsened after the corruption scandals in 2016, and became especially extreme after the coup attempt in 2019. Since then, the country has been increasingly governed by decrees and the parliament has become, without exaggeration, a useless institution. Strict censorship and pressure on the media were followed by the closure of hundreds of opposition media outlets and the seizure of all of their assets by the state. Thousands of journalists have been left unemployed by the government, including editors, reporters, writers, photographers, camerapersons, translators, and many others. Some jobless journalists stayed in the country, some of those who had the opportunity to move abroad left (CPJ, 2019).

For senior journalists who became jobless it was relatively easy to move on, because they had reputations and were able to attract audiences when they spoke in public. Some more prominent journalists have moved into alternative journalism as a means to continue within their profession by starting YouTube channels, podcasts, or new websites. Financially, they found ways to survive either through crowdsourcing or donations, but they primarily applied for funding opportunities from international non-governmental organizations and civic foundations. It follows to consider whether these digital channels are alternatives to the government’s mainstream media or not.

First, it is necessary to define the alternative media: alternative to what? Of course, it is defined in opposition to the mainstream media. Mainstream media is profit-oriented, open to demands from governments and states, and focused on advertising. It treats news as a commodity, and readers and viewers as customers. It is hierarchical and, in the pursuit of commercial interests, benefits those highest in power. Mainstream media manipulates in the interest of maintaining the status quo. That is why mainstream media all over the world produce ‘fake’ news. It reflects the interests of the bourgeoisie, so it is constantly trying to sell something to the public, whether it is information as news or advertisements. But mostly, the mainstream media represents the ideology of the ruling class.

In contrast, a digital media channel with alternative tendencies has the responsibility to demonstrate its rejection of the above described diseases cultivated and spread by the mainstream media. Audiences expect alternative media to behave differently from the mainstream in terms of ownership, content production, and distribution, and demonstrate an understanding of news values different from the mainstream. It should be open to the voices of minorities and marginalised groups without representation in the mainstream media.

Alternative journalists’ business philosophy should be different from that of mainstream journalists as well. In terms of the audience’s attitude towards the profession, the understanding of news should also be different. Readers, viewers, and followers have to choose alternative news sources on their own and for the right reasons: buying, watching, and demanding it because it’s better than the other options. Alternative media has to develop a different language and discourse than the mainstream media and a different understanding of journalistic ethics. Alternative media can include outlets that comply with ethical standards, on language, for example, but also outlets that produce anarchist or hacktivist content in the public interest, like Wikileaks. This text focuses on alternative channels producing news content within ethical standards.

There are four types of alternative media in today’s Turkey:

- Partisan, anti-government niche newspapers printed on paper (Examples: Evrensel, Birgün).

- Online newspapers, podcasts, and websites established by prominent journalists, in Turkey or in exile, whose employment was terminated. These publications were established as a result of AKP’s oppressive media policies and were forced into alternative media. The founders of these platforms established alternative media channels after losing their jobs with mainstream media outlets due to dissident reporting (Examples: T24, #ÖzgurRadio, Corrective, Duvar., Medyascope.tv, Ünsal Ünlü YouTube channel, Cüneyt Özdemir YouTube channel).

- Online Kurdish media in Turkey or exile (Examples: Özgür Gündem, Yeni Yaşam, Artı Gerçek).

- Digital news platforms that engaged in digital alternative journalism long before AKP’s oppressive regime; channels that are alternative from ‘birth’ (Example: Bianet).

Evrensel and Birgün are particularly left-wing publications that started publishing with low circulation figures long before the AKP came into power. Left wing papers’ circulation and ad revenues have never been high in Turkish media history. However, after the AKP’s oppressive media policies, interest in online versions of these two newspapers has increased. Social media helps disseminate web versions of these newspapers’ content to a wider audience even as their print circulation remains steady.

The diaspora of ethnic Kurdish media have been broadcasting and publishing before and after the AKP came into power and continue to fight for ethnic and political rights. These publications continuously reemerge under different names to combat the ceaseless closures and bans on their businesses.

Bianet, which began with the support of the EU’s MEDA Fund in 2000, fits the definition of an alternative media source, considering its non-hierarchical business structure, differentiated news values, rights-based news content and the working conditions of its employees. At Bianet, all journalists are on salary and insured, managing and editing responsibilities are rotational, and a commitment to alternative values is visible across the news language, ethics, and no-ads policy. Bianet has achieved worldwide success and helped raise awareness about rights-based journalism through their news content. They further promote this journalistic standard through regular seminars and lectures with young journalists and push mainstream media to change its news language as well.

Looking at examples of media companies created by unemployed or exiled, formerly prominent journalists, we see a different picture. First of all, it is necessary to examine their understanding of alternative media. Journalists who came to prominence through mainstream media did not go alternative by choice. According to senior columnist Kadri Gürsel, who was forced to leave his job at Milliyet, the only medium where true journalism can be practiced is the mainstream media (2018). Even though he, assumedly temporarily, works in alternative media channels, he maintains that high-quality, honest, and professional journalism can only be created with the support of mainstream outlets. Gürsel is one of many journalists who are looking forward to returning to the mainstream media once the media restrictions are lifted.

This point of view runs counter to a large academic corpus on journalism-state relations demonstrating that the mainstream media fails to present accurate information due to its commercial nature and corrupt relations with the state and bourgeoisie. It is important to remain skeptical of new media spaces created by journalists who had to leave the mainstream and enter into alternative channels unwillingly. Do these journalists bring the poor working conditions and tired newsroom habits of the mainstream into alternative spaces? Are bad habits like mansplaining, sexism, and racism, and corrupt practices like nepotism and labour exploitation being reproduced in the alternative media? Are journalists forced into working in alternative media creating alternative newsrooms, or is the old patronage-based structure continuing in a different form?

The financial structure and sustainability of alternative media outlets is another issue worthy of discussion. To understand the financial question, it is important to understand how alternative media channels are structured and operated. A YouTube channel created by a single journalist has a simpler path to survival. A newsroom with dozens of reporters and technical personnel is a different case entirely. Can they accept ads for revenue, or do they have a no-ads policy? The dependence on advertising and donations goes against a commitment to alternative media values by making journalists appease the advertisers and their values. In the mainstream media, executives and salespersons handle the advertisers; journalists do not deal with them directly. Forced into new roles of leadership as owners of alternative media outlets, journalists have to deal with companies and their advertising departments directly. This creates a conflict of interest in independent journalism. Is it possible to be alternative while simultaneously bargaining for ads and commercials alongside producing real journalism? Journalist and labour unionist Murat İnceoğlu asks the same question (2021): “If you don’t create an alternative working condition internally, you cannot be alternative after all. Without an accountable, democratically functioning, and transparent newsroom, only a small copy of the mainstream will emerge.” İnceoğlu is referring to journalists who are imitating their old media bosses while trying to find ways to continue their journalistic practices in alternative spaces. He also describes the working conditions of alternative media journalists, their poor compensation, and their exploitation by the new media leadership.

Due to their good reputations, prominent journalists have greater access to domestic and international donations from different foundations. They are also more successful with crowdsourcing and subscriptions for funding their media operations. However, these channels still do not reach a large audience and their following in the country remains limited; this presents a potential problem for their financial models. Research conducted by the Reuters Institute shows that the mainstream media is the main source for news for the masses, especially TV channels controlled by the AKP government. According to the results of the survey, although seventy percent of media consumers in Turkey do not trust the media, seventy-two percent still get their news from mainstream TV channels (Euronews 2020).

In conclusion, the despotic and oppressive media policies of the AKP regime has led journalists to find alternative ways to inform the public about what is really going on in the country. Are these new channels genuinely alternative? Financially and culturally, there is evidence that brings many of these channels’ commitment to alternative journalistic practices into question, particularly their continued dependence on international funding and/or crowdsourcing for their operations – a weak model due to the lack of self-sufficiency. Current models of alternative media also make the peer-to-peer working conditions of the journalistic sphere complicated. Alternative journalists need to find ways to sell their content to the public, and the public needs to somehow understand the value of alternative journalism. The ideal media landscape would promote the proliferation of a patronage-free, ethical, and sustainable alternative media in Turkey, not only in the interest of the freedom of the press but also for the freedom of journalists. Turkey needs alternative media by choice. Of course, an independent, alternative media would greatly benefit from stronger demand from the greater public and stronger financial support from the people.

Sources

CPJ (2019). “For Turkish journalists in Berlin exile, threats remain, but in different forms”, https://cpj.org/2019/07/for-turkish-journalists-in-berlin-exile-threats-re/, (last seen 14.04.2021)

Euronews (2020). “Araştırma: Türkiye’de halkın yüzde 70’i medyaya güvenmiyor, haberi TV’den alanların oranı yüzde 72”, https://tr.euronews.com/2020/06/10/arast-rma-turkiye-de-halk-n-yuzde-70-i-medyaya-guvenmiyor-haberi-tv-den-alanlar-n-oran-yuz, (last seen 15.03.2021)

Gürsel, Kadri (2018). “Ana akım medyanız nasıl olsun?”, Birikim Dergisi, 27 Kasım 2018, https://birikimdergisi.com/haftalik/9226/ana-akim-medyaniz-nasil-olsun, (last seen 15.03.2021)

İnceoğlu, Murat (2021). “Yayında alternatif, işleyişte ana akım olunur mu?”, https://sendika.org/2021/02/yayinda-alternatif-isleyiste-ana-akim-olunur-mu-609122/, (last seen 15.03.2021)

Associate Professor Esra Arsan received her Ph.D from the Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Journalism of Marmara University, Turkey. She has worked as a lecturer in journalism at Istanbul Bilgi University between 1998 and 2017. Between 2012 and 2017, she worked as a researcher and gave courses for the graduate students of the Cultural Studies program at the same university. She is a former fellow of Thomson Reuters Institute of Journalism in Oxford. Her research interests are political communication and the practice of political journalism in Turkey. Due to current political crisis and government’s pressure on the universities in Turkey, she has resigned from her position at Istanbul Bilgi University in January 2017, moved to Aegean part of the country, and started working as an independent scholar. Arsan has tree books published: Medya Gözcüsü (Media Watch), AB ve Gazetecilik (EU and Journalism) and Medya ve İktidar (Media and Power-with Savaş Çoban).

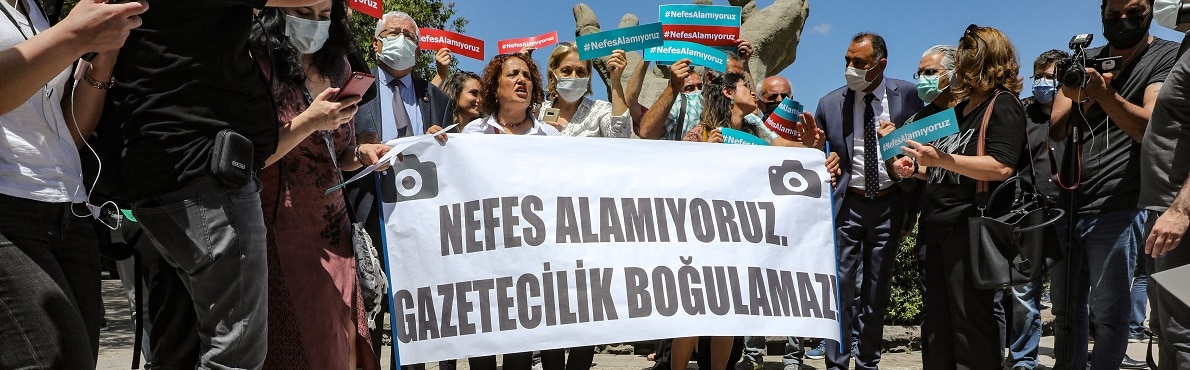

Cover Photo: People stand behind a banner reading in Turkish “We can’t breathe. Journalism cannot be drowned!” during a rally outside the offices of the Governor of Ankara – June 29, 2021 (Adem ALTAN / AFP).

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.