On November 1st a little over 23% of Algeria’s eligible voters cast their vote in the referendum for constitutional reform called by President Abdelmajid Tebboune. Since no quorum was required, the amendments were nonetheless approved with 67% of votes in favour according to official data.

Opposition parties, which had asked the people to boycott the referendum, consider the outcome a victory and are convinced they have weakened the government and the presidency. Although the victim of strong repression, Hirak, the anti-government protest movement founded in February 2019, continues to call for the beginning of a democratic process.

“One needs to divide by ten the turnout figures provided by the authorities and tell the truth…” said a caustic Karim Metref, an Algerian journalist, blogger and teacher who lives and works in Turin.

According to observers, abstention reached historic levels: is that correct?

To be truthful it was the same as in the December 2019 presidential elections (the first since Abdelaziz Bouteflika resigned in April, ed.), it is just that the regime was even more strongly trying to legitimise the voting by sending agents and soldiers in civilian clothing, as well as state employees, to the polling stations. This time there was a lack of homogeneous consensus within the apparatuses themselves. For example, a number of Armed Forces units with Arab links complained about amendments concerning the identity of the Amazigh minority and the Tamazigh languages and in the end these changes were downsized.

Reform detractors speak of feigned changes and a strengthening of the head of state and the army’s prerogatives. There has, however, been one important change: the rejection of traditional Algerian military non-interventionism. The Armed Forces will now be able to take part in exercises, peace-keeping and peace enforcing operations abroad under the aegis of the United nations, the African Union and the Arab League.

Indeed, and that abolishes an independent Algeria’s anticolonial principle: non-interference in the affairs of other countries. Obviously the second largest African army, the Algerian one precisely, is more interested in regional and international players. Remember that Algeria accounts for 30% of the African continent’s military expenditure.

Should one perhaps expect Algerian military activity in regional theatres?

It’s hard to say. What is certain is that Algeria is the only country capable of intervention in Libya. It is probable that Algeria’s Air Force has already taken action to stop ISIS (in the summer of 2014, specific night time raids on jihadist posts wiped out the caliphate’s new-born province in Libya. In the absence of reliable claims, observers attributed these raids to Egypt, the UAE, Israel or Algiers). The Egyptian Air Force, however, is prevented from taking such initiatives by the Camp David agreements.

What is the Algerian regime’s position with regards to Turkey? Is a new axis being formed to Tripoli’s advantage?

Ankara and Algiers are certainly not reading off the same page as far as Libya is concerned. Libya, however, is not the only source of instability for Algeria; consider Mali for example. As far as the interests of regional players are concerned, I would mention pressure that Riyadh applied in vain on Algiers in the days of its intervention in Yemen (March 2015)…

Returning to the referendum, this reform was presented as the appropriate answer to the expectations of the Hirak activists. So why was there such a complete boycott?

Because not only did it not introduce any real, substantial changes requested by civil society and political opposition parties, but there was also no attempt to involve them in the constitutional process. Abstentionism at this level is an insult to the legitimacy of this government and this presidency.

The projects of the Algerian regime, whatever they may be, risk never leaving the starting post. According to the Saudi press, President Tebboune is in a coma.

Yes, there is a great deal of talk. Officially he was urgently moved to Germany for treatment. The Saudis say he is in serious conditions and in a coma. Anything is possible – COVID-19, poisoning. And so Algeria is now a country risking total instability, although Major General Saïd Chengriha is more moderate compared to his predecessor (Ahmed Gaid Salah, the Algerian Army’s Chief of Staff who died in December 2019); he may start a new phase of political and social dialogue between Algeria’s different souls and it may be the right time for this.

So the Tunisian way..

Yes. The opposition too is interested in finding a solution for Tunisia and it is a moment that should be exploited. Nowadays there is great distrust as far as the army is concerned and people are accusing the generals of being those most responsible for the current situation. The hope is that with support from young officers the army will return to be a guarantee.

Political dialogue cannot disregard decisions concerning economic relaunching. How serious is the situation in your opinion?

Compared to nearby nations, Algeria has the advantage of not being in debt to international organisations thanks to capital coming from the hydrocarbon sector. It is however known that, over the coming 20 years, Algeria’s reserves will be finished. All the chickens will come home to roost, as will the need for real productive programmes rather than colossal infrastructures that have no long-term effect.

Algeria seems to be moving closer and closer to the precipice. What options are there now in your opinion?

If we want to avoid a worse case scenario there is no choice. We will have to find the strength to create a constituent assembly, accept the presence of all of society’s representatives at the negotiating table and work towards a real transition.

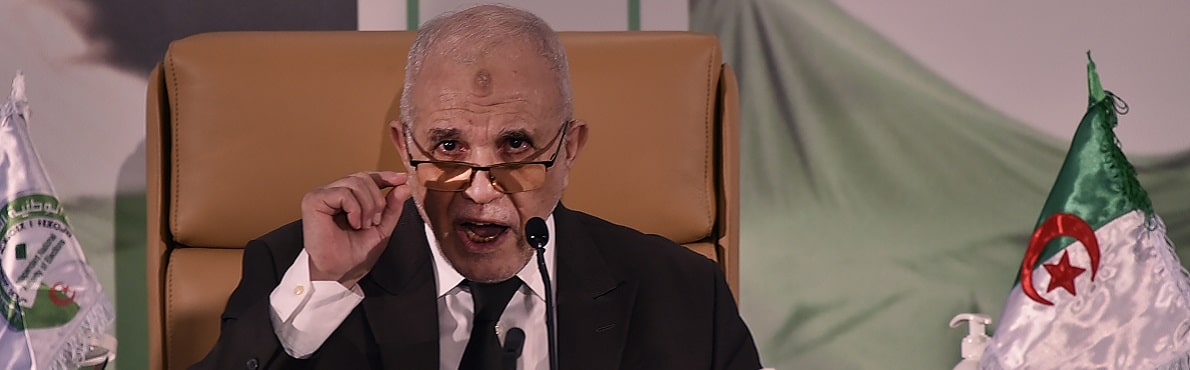

Cover Photo: National Independent Elections Authority (ANIE) chief Mohamed Charfi speaks in Algiers in the aftermath of the country’s constituional referendum – November 2, 2020 (Ryad Kramdi / AFP)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to share and interact with our contents.

If you like our stories, videos and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).