Before the summer of 2019, few would see that Hong Kong, a supposedly autonomous and self-ruling city of China, formerly a British colony, could be anything significant aside from a prosperous business and financial hub, let alone believing its relationship with China could be something consequential. With more than a quarter of its population getting onto the street, followed by the authority’s violent suppression and crackdown, the city drew global attention. Suddenly, the world started asking, “What is happening in Hong Kong?” Since then, numerous books and articles have emerged in an attempt to answer the question. While the conflict is often understood as merely a political struggle between Hongkongers fighting for their political rights and freedom on the one side, and the ruthless authoritarian Chinese Communist Party on the other side, sharing by nature no difference with other democratic movements elsewhere over the previous decades, some deeper and more fundamental factors driving the conflict, however, may be easily overlooked.

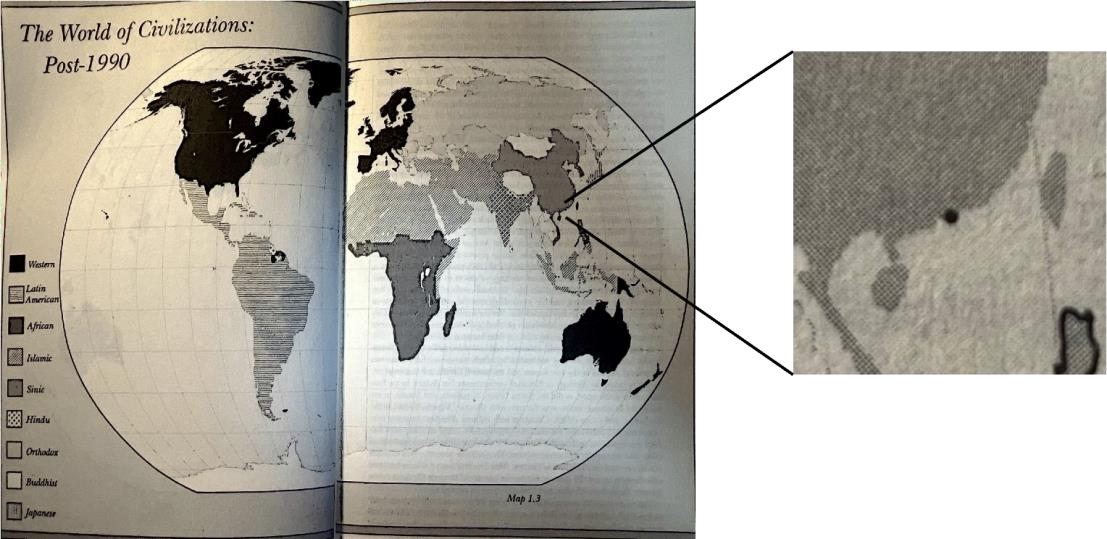

In 1996, Samuel Huntington controversially divided the world into eight different civilizations1, by which he claimed that “in the post-Cold War world, the most important distinctions among peoples are not ideological, political, or economic,” but culture and identity, that people “use politics not just to advance their interests but also to define their identity”2. When I read the map, a detail immediately attracted my sight: while most of China was defined as “Sinic”, Hong Kong was distinctively defined as “Western” (Fig. 1). Hong Kong was considered a different civilization from its neighbour. Indeed, one possible explanation might be due to the fact that at the time when the map was drawn, Hong Kong was still under British rule, and it was thus conveniently categorized the same as Britain. After re-examining the Hong Kong-China relations and their respective narratives on their contentions, however, I was convinced that Hong Kong has indeed been developed into a unique civilization, that deviated from that of China, which fundamentally fuels the conflict between them.

It is noteworthy that while highlighting the civilizational difference between Hong Kong and China, it does not automatically entail the conclusion that Hong Kong is a Western subject. Given that Hong Kong’s traditional culture, language, and ethnicity still share far more similarities with the Chinese than the Westerners, one could hardly see Hong Kong as entirely of the Western civilization. Instead, it is argued that Hong Kong is in itself a “dual-peripheral civilization,” simultaneously heavily influenced by two major civilizations3, the Chinese and the Western, while none of them either could exclusively define it. In other words, Hongkongers would be seen by the Westerners as “too Chinese,” however meanwhile, would be seen by the Chinese as “too Westernized.”

Focusing on the clash of civilizations between Hong Kong and China, this paper will first explain how Hongkongers were sprung out from the Chinese civilization under British rule. It would then lay out some conflicting understandings between Hongkongers and Chinese on some key concepts due to the civilizational difference. Finally, it would portray how the conflicting understandings have been driving their political conflict over the previous decades.

Departing from China

When the British troops first time landed in Hong Kong in 1841, they saw only a “barren rock with nary a house upon it”4. Apparently, it was not the British intention to build a prosperous city nor an international financial hub in East Asia, instead, the only reason why the barren rock was colonized at first, was to set up an entrepôt for the British traders to access China’s market. The founding of Hong Kong was primarily commercial, and the British had shown no interest in governing the local Chinese inhabitants, as long as their business was not disturbed. This approach was revealed in the segregation between the European and the local Chinese during the early decades of British rule when the local Chinese community was largely self-governed without being bothered by British intervention nor legislation.5

In fact, for the first century of British rule, there was no sign that Hong Kong would in any sense be “Westernized.” Especially when there was no border control between Hong Kong and China before 1950, there was indeed “free and regular movement of people to and from China”6, the way of living and thinking of the ethnic Chinese in Hong Kong were still largely similar to those in China. Following the Chinese Civil War in the late 1940s, there was an influx of Chinese immigrants escaping from the political turmoil in China. With the fear of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), a number of Chinese capitalists and industrialists, carrying their capital and industrial technology, also flocked into Hong Kong. At the moment when the Hong Kong government decided to set up a border with Communist China in 1950 due to the Cold War, the population of Hong Kong had surged to over 2 million from only about 600,000 in 19457. Taking advantage of the vast amount of permanent population after setting the border, with considerable capital and industrial technology, Hong Kong transformed from merely an entrepôt to an industrial city.

With the economic success, the British were motivated to advance their governance and administration in this city, including providing public service, housing, and education. The British common law tradition and the concept of the rule of law were also widely introduced to the population during the period. Although these Western concepts first appeared to be difficult to understand by the ethnic Chinese population, they still saw the concepts as attractive when compared to “the lawless horror in the near-totalitarian political system” 8 of Mao Zedong’s Communist China. Thereafter, by the 1970s, basically Hong Kong people of all ethnic origins had embraced these Western concepts.

The acceptance and prevalence of the common law system and the rule of law was a significant step when the way of living and thinking of the people in Hong Kong started to depart from the Chinese tradition. In traditional Chinese culture, heavily influenced by Confucianism, people treasure human relationships (人倫關係), which is seen as a basic component of social structure and harmony. And one has more obligations to people with closer relationships than the others. There is a famous quote in the Analects, a record of Confucius’s teachings which is sometimes analogized to the “China’s Bible”9:

“The father conceals the misconduct of the son, and the son conceals the misconduct of the father. Uprightness is to be found in this.” (父為子隱,子為父隱,直在其中矣)10

The philosophy beneath is that one should always put the interests of those with closer relationships with you above the others. So, when there is misconduct of your family members, those with closest relationships with you, your obligation is to protect them. This idea, however, is substituted by the common law system and the rule of law in Hong Kong, where contractual relationship is seen as more vital to structuring a society, and the emphasis on human relationships would often be considered fostering corruption. As we will discuss later, this division between human relationships and contractual relationships has then led to some key conflicting understandings between Hong Kong and China.

In the latter part of the 20th century, Hong Kong was part of the “Asian Miracle”11, driving the economy of East Asia. Meanwhile, since the 1970s, civil society in Hong Kong developed rapidly, raising general public awareness of their civil rights and liberty. Subsequently, in the early 1980s, when the negotiation between British and Chinese governments over Hong Kong’s future began, Hongkongers were enjoying economic prosperity and political freedom, in contrast to China when it was still recovering from the political, social, and economic instability of the Cultural Revolution. This created Hongkongers a sense of privilege, who saw themselves as “enlightened Chinese,” and more civilized than those in China12. Attributing their success to the “enlightened” values brought by the British, following the Sino-British Joint Declaration signed in 1984 when Hong Kong was decided to be handed over to China in 1997, some Hongkongers saw that it was their obligation to bring enlightenment to China. The prevalence of the “theory of democratic return” (民主回歸論) at the time, precisely suggested that the democratization of Hong Kong could “serve as a model to facilitate greater political openness” in China13.

Conflicting Understandings

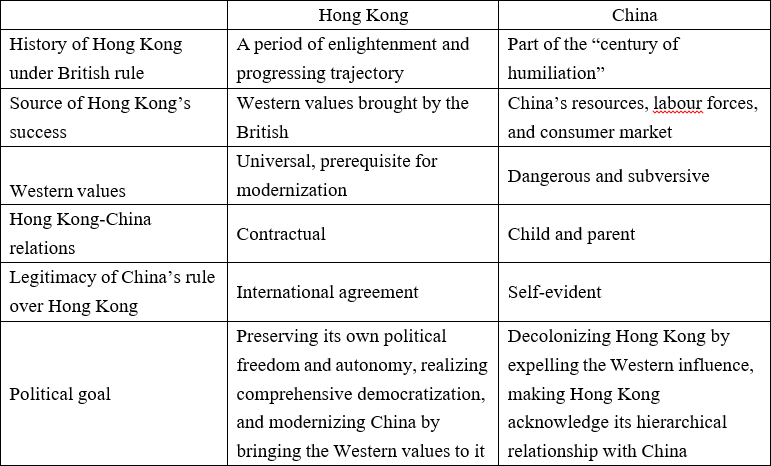

In June 2004, 7 years after the handover, nearly 300 Hong Kong professionals and scholars made a joint statement “Standing Firm on Hong Kong’s Core Values,” defining the core values of Hong Kong, which also led to its advantage, as “liberty, democracy, human rights, rule of law, fairness, social justice, peace and compassion, integrity and transparency, plurality, respect for individuals, and upholding professionalism.” It further stated that “defending these core values is not just for the sake of preserving Hong Kong’s way of life, it serves to continue the cultural mission of modernizing the Chinese nation as a whole”14. Coherent to the “theory of democratic return,” the joint statement underlaid some fundamental beliefs of Hongkongers at that time: (1) The Western values brought by the British are Hong Kong’s core values, central to the success of Hong Kong; (2) These values are universal, which are prerequisites for a nation to be modernized; (3) Hongkongers, with better understanding on these values, are having the obligation to modernize China by exercising these values.

While these are Hongkongers’ fundamental beliefs, China, however, is fundamentally opposing them.

China, once commented as a “civilization pretending to be a nation-state”15, had long enjoyed isolation from other great civilizations in the world for most of its history, surrounded only by poor tribes in the periphery, which were considered by China as “barbarians” (蠻夷). It nurtured a sense for China to see itself as the center of the world, reflected in its name, the “Middle Kingdom” (中國). In the middle of the Middle Kingdom, stood the Chinese Emperor, which in Chinese means the “Son of Heaven” (天子), who was mandated directly from heaven to maintain the “Great Harmony” on the earth by keeping the social (and international) hierarchy. Therefore, China as itself a civilization, “was never engaged in sustained contact with another country on the basis of equality”16, because there is no way for the Son of Heaven to be equal to any others, especially those from the uncivilized periphery. It does not mean that China had never been successfully conquered by foreigners. In those cases, however, those foreign conquerors would be served by the Chinese bureaucratic elite, being taught the Chinese way of ruling, thinking, and living. They often found themselves being assimilated into China while ruling it1718. After all, China as a civilization remained to thrive.

It is thus imaginable that when the Europeans arrived China in the 18th century, asking not for land nor resources, but for free trade and diplomatic relations on an equal basis, concepts never existed on Chinese soil before, they seemed to be aliens in the Chinese Emperor’s eyes. The tension between China and European countries, centering on the issues of free trade, resident embassies, and system of diplomatic exchange, had been rising since then, leading to a series of military conflicts in the 19th century, with China being defeated in virtually every battle and was forced to accept virtually every terms and conditions proposed by the Western forces. It was not the first time China was militarily defeated by foreigners, but it was the first time when its civilization was not attractive to these invaders. Worse still, they came and proposed to replace their whole system “with an entirely new vision of world order”19. It was the first time in its history that China as a civilization was threatened.

For the Chinese, it was too much of a shock that the period is namedview on their history of British rule, a period of enlightenment and progressing trajectory, China sees it as part of the humiliation it suffered. To get rid of this humili the “century of humiliation”20, when China was repeatedly forced to open its ports and domestic market to the Western powers, and to do trade and diplomacy following the Western guidebook. Hong Kong also fell to the British hand during this “century of humiliation”. Therefore, contrasting with Hongkongers’ ation, taking back control over this territory is thus necessary. In 1982, despite the British government’s attempt to persuade China that maintaining the status quo of Hong Kong under British administration, with the rule of law, common law tradition, and capitalist economic system, is beneficial to all parties including China, China firmly stood on the position that China’s sovereignty and administration on Hong Kong are both non-negotiable21. As a result, by promising to preserve Hong Kong’s social and economic system, as well as granting Hongkongers political autonomy, China successfully reclaimed Hong Kong as part of its territory. To China, it signified its victory over a Western power after the “century of humiliation.”

As mentioned, Hongkoners at that time saw themselves as having the obligation to bring Western values, which had led to their own success, to China and modernize it. However, China does not consider those Western values as a source of success and modernization, instead, Hong Kong’s success is attributed to China’s resources, labour forces, and consumer market22. Rather than positive factors, those Western values are even deemed as dangerous and subversive. And Hongkongers, a group of Westernized people in its periphery, are also potentially subversive. Since the handover in 1997, China has always been accusing Hongkongers of having a “colonial mentality” or “Western-looking mentality,” who need to be “decolonized” by the Chinese civilization23.

Another angle to understand the conflicting understandings between Hong Kong and China, is their respective view on the Hong Kong-China relations. Brought up by the common law tradition, Hongkongers stress emphasis on contractual relationships, the legitimacy of China’s rule on Hong Kong is therefore laying on the international agreement, namely the Sino-British Joint Declaration signed in 1984. And China should also stick to its promise by restricting itself from intervening in Hong Kong’s freedom and autonomy. To the Chinese, however, their legitimacy of ruling Hong Kong is self- evident. Adopting the Confucianist view of human relationships, China has always been using the kinship metaphor, seeing itself as the parent of its neighbours and ethnic minorities24. As no one would challenge the hierarchical relationship between a father and a son, China’s power over Hong Kong should also be unchallengeable. And for China, Hong Kong is not only a child, but a “spoiled child” badly influenced by the Western colonizer, thus “threatening the harmony of the big Chinese family”25. In response, China takes it as its responsibility as a parent to “educate” Hong Kong, to make it “know thy place”26 by acknowledging its hierarchical relationship with China, and to share the glory of rejoining the “big Chinese family.”

A Vicious Circle

On the Hongkongers’ side, they wish to maintain their advantage by preserving political freedom and autonomy, and seeking comprehensive democratization, while seeing the authoritarian China as “less-modernized” and “yet to be enlightened.” On the Chinese side, they wish to restore the order and hierarchy of the “big Chinese family,” and Hong Kong as a Westernized “spoiled child” is yet to be “decolonized” and learn how to once again be Chinese. These conflicting understandings are fundamental to the post-handover tension between Hong Kong and China, which eventually leads to a vicious circle: the more Hongkongers ask for political freedom, autonomy, and democracy, the more China finds Hongkongers are proved to be “infected” by the Western powers27, and therefore it is necessary to tighten its control over Hong Kong before going too much disorder, which further provokes the Hongkongers to believe that they have no choice but to protect themselves from China’s authoritarian intervention by more freedom, autonomy and democracy28.

The vicious circle was even intensified after Xi Jinping came into power. In November 2012, right after Xi assumed office as China’s president, he declared, “We must make persistent efforts and strive to achieve the Chinese dream of great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”29. Soon after his speech, the ideas of “China dream” and “national rejuvenation” were echoed by state media and propaganda, becoming the central thoughts of Xi’s administration. The underlying idea beneath the slogans of China dream and national rejuvenation is that after the “century of humiliation” when China was “semi-colonized” by Western powers30, China is now rising, not only politically and economically, but also culturally and ideologically. As emphasized by Xi in 2014, all Chinese should uphold the “Four Confidences” (四個自信), namely “confidence in path” (道路自信), “confidence in theories” (理論自信), “confidence in system” (制度自信) and “confidence in culture” (文化自信), as a fundamental guideline along their struggle of development31. With this narrative, those Hongkongers not aligning with the confidence as Chinese, but still embracing Western values, are more of a problem for China. Since then, China has been advocating for the concept of “second return” (二次回歸), by which, Hong Kong should not only be politically and territorially returned to China, as it did in 1997, but also culturally and ideologically, so as to “crush the Western anti-China values”32 rooted in Hong Kong.33

To accomplish the “second return” of Hong Kong, China tried to implement patriotic education in 2012, and then published a Chinese government white paper in 2014, referencing its “comprehensive jurisdiction” (全面管治權) over the territory34, when both met with serious pushback from the Hong Kong civil society through large-scale social movements. With China showing no intention of facilitating political openness, Hongkongers soon found that their own political freedom and autonomy were on edge, they thus realized that “they have neither the resources, the ability, nor the responsibility to democratize China”35. The “theory of democratic return” had been rapidly substituted by the prevalence of Hong Kong nationalism, with a fraction of those clearly advocating for independence. As explained by Baggio Leung, a Hong Kong nationalist political leader in 2018, while China had historically never allowed the separation of power, Hong Kong could never genuinely enjoy autonomy and democracy under Chinese rule, therefore, in order to preserve Hongkongers’ way of living and thinking, “independence is logically the only way out”36.

Indeed, the emergence of Hong Kong nationalism and separatism further touched the nerve of China. To China, it was nothing but a political campaign manipulated by the Western powers in an attempt to block China’s way toward its national rejuvenation37. And Hongkongers, embracing the Western powers and rejecting China’s rule, were seen as traitors not only to the Chinese government, but to the entire Chinese civilization. To restore civilizational order, to make Hongkongers “know thy place,” and to attain Hong Kong’s “second return,” following the mass protest in 2019, China severely cracked down the civil society and political opposition in Hong Kong. In 2020, China imposed the notorious national security law, outlawing the acts of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces, which also subjugated the common law tradition and judicial independence in Hong Kong by stressing the law’s superiority among other local laws38. Since then, hundreds of Hongkongers were imprisoned due to the law, including dozens of political leaders, journalists, lawyers, scholars, and other professionals who were “too Westernized,” with thousands more activists being arrested due to some other charges, and more than a hundred thousand have fled from the city to mainly the Western countries, with the majority of them making their former colonizer, Britain, as their destination. And the Western values, as well as many of those who actively embraced them, were finally expelled from the territory.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Conflict

In 1997, when Chris Patten, the last governor of Hong Kong before the handover, was asked to conclude the one and a half century of British colonial rule in Hong Kong, he replied, “I think that Hong Kong is an astonishing Chinese success story with British characteristics”39. As argued, Hong Kong is a “dual-peripheral civilization” of two major civilizations, where neither the Chinese nor Western civilization can exclusively define it. This paper presents a civilizational lens on the conflict between Hong Kong and China since the handover. Although China has actively sought to subjugate Hong Kong entirely under its own civilization, seen by Hongkongers as “less- modernized,” the attempt was fundamentally rejected, a position which China conceives as a betrayal.

Today, China has declared its success in achieving the “second return” of Hong Kong, by placing it under China’s comprehensive control40. At the time of concluding this paper in 2024, the Hong Kong Legislative Council just passed the new national security legislation, which was claimed to be “complementing” the 2020 national security law41. Mass protests and political opposition publicly calling for freedom, autonomy, and democracy have indeed ceased to exist in Hong Kong. The conflict, however, is far from being ended. Following the mass exodus, Hongkongers have created a global diasporic community, who are still preserving a strong sense of Hongkonger identity and calling to counter against the authoritarianism in China and Hong Kong42. With the vast majority resettling in the Western countries, they can reasonably be perceived to cultivate an even stronger tie with the Western civilization in the future. And it is believed that the clash between those Westernized Hongkongers, and those Chinese confident with their own civilization, will continue, though subtly, in the foreseeable future.

Notes

1 Samuel Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 26-27.

2 Huntington, Clash of Civilizations, 21.

3 Here I borrow the concept of “peripheral civilization” from Philip Bagby, please see Culture and History: Prolegomena to the Comparative Study of Civilizations (California: University of California Press, 1958).

4 Frank Welsh, A History of Hong Kong (London: Harper Collins, 1993), 1.

5 Steve Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong (London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2007), 65-66.

6 Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong, 181.

7 Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong, 167.

8 Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong, 182.

9 Henry Kissinger, On China (London: Penguin Books, 2011), 13-16.

10 “Confucianism, The Analects, Zi Lu, 18“, Chinese Text Project, accessed 17 June 2024.

11 John Page, “The East Asian Miracle: Four Lessons for Development Policy”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual, Volume 9 (1994): 219, https://doi.org/10.1086/654251

12 This sentiment was well-captured by some Hong Kong movies at that time, for example “Her Fatal Ways” (1990), in which the Chinese characters were often portrayed as “country bumpkins”.

13 Chin Wan, On Hong Kong as a City-State 香港城邦論 (Hong Kong: Enrich Publishing, 2011), 22.

14 “Standing Firm on Hong Kong’s Core Values”, Hong Kong Great Speeches, accessed 17 June 2024, https://hkspeech.wordpress.com/2004/06/07/%E7%B6%AD%E8%AD%B7%E9%A6%99%E6%B8% AF%E6%A0%B8%E5%BF%83%E5%83%B9%E5%80%BC%E5%AE%A3%E8%A8%80/

15 Lucian Pye, “Social Science Theories in Search of Chinese Realities”, China Quarterly, 132 (1992): 1162, http://www.jstor.org/stable/654198

16 Kissinger, On China, 16-17.

17 One example is the Manchus, a tribe originally lived in the north-east of China. After seizing control of Beijing in 1644, they claimed mandate from heaven and established the Qing dynasty, ruling China for nearly three centuries before being overthrown in 1912.

18 Kissinger, On China, 22.

19 Kissinger, On China, 33.

20 Alison Kaufman, “The ‘Century of Humiliation’ and China’s National Narratives” (10 March 2011), accessed 17 June 2024, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/3.10.11Kaufman.pdf

21 Chi-Kwan Mark, “To ‘educate’ Deng Xiaoping in capitalism: Thatcher’s visit to China and the future of Hong Kong in 1982”, Cold War History (2015): 1-3, DOI: 10.1080/14682745.2015.1094058.

22 Stephen Vines, Defying the Dragon: Hong Kong and the World’s Largest Dictatorship (London: Hurst & Company, 2021), 45.

23 Ibid.

24 Kevin Carrico, Two Systems, Two Countries: A Nationalist Guide to Hong Kong (California: University of California Press, 2022), 118-119.

25 Chen Hao, “Responding to the domestic violence of Hong Kong independence in step with the times”, Journal of the Fujian Institute of Socialism 104, no. 5 (2015): 104.

26 Kissinger, On China, 15.

27 Carrico, Two Systems, Two Countries, 143-150.

28 Chin, On Hong Kong as a City-State, 22.

29 “What does Xi Jinping’s China Dream mean?” BBC News (6 June 2013), accessed 17 June 2024, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-22726375

30 “Xi Jinping: Carrying on from the past to the future, continuing to advance towards the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” 习近平:承前启后 继往开来 继续朝着中华民族伟大复兴目标奋勇前进, Xinhua News (29 November 2012), accessed 17 June 2024, http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2012-11/29/c_113852724.htm

31 Wang Jianshen 汪建新, “Why did General Secretary Xi emphasize ‘confidence in culture’ in his 1

July speech?” 习总书记“七一讲话”为何强调“文化自信”?People’s Daily Online (4 July 2016), accessed 17 June 2024, http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0704/c1003-28522592.html

32 Zhang Wenji, “The Meaning of Hong Kong’s second return” 香港二次回歸的意義, US-China

Forum (16 July 2022), accessed 17 June 2024, https://www.us- chinaforum.com/27599369133554222727/1210558

33 Chan Kinglap 陳競立, “Hong Kong needs second return” 香港需要二次回歸, Oriental Daily

News (25 June 2020), accessed 17 June 2024, https://hk.on.cc/hk/bkn/cnt/commentary/20200625/bkn- 20200625000433631-0625_00832_001.html

34 “The Practice of the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ Policy in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region White Paper (Full-text)” “一國兩制”在香港特別行政區的實踐白皮書(全文), Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR (10 June 2014), accessed 17 June 2024, http://big5.locpg.gov.cn/jsdt/2014-06/10/c_126601135.htm

35 Chin, On Hong Kong as a City-State, 58-59.

36 “‘Only we are Hongkongers in the world’ – A review of the tertiary students’ forum on 1 July”「世界上只有我們是香港人」—回顧大專學界七一論壇, University Community Press (2 July 2018), accessed 17 June 2024, https://cusp.hk/?p=8183

37 Song Xixiang, “The latest characteristics of the development of the ‘Hong Kong independence’ and the responding strategies” “港獨”勢力發展的最新特點及其應義策略, Journal of the One Country Two Systems Studies 34, no. 4 (2017): 89-90, https://www.mpu.edu.mo/cntfiles/upload/docs/research/common/1country_2systems/2017_4/11.pdf

38 Michael Davis, Making Hong Kong China (Ann Arbor: The Association for Asian Studies, 2020), 77-80.

39 “Legislative Council Official Record of Proceedings”, Hong Kong Legislative Council (19 June 1997), 370, https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr96-97/english/lc_sitg/hansard/970619fe.doc

40 Zhang, “The Meaning of Hong Kong’s second return”.

41 “Safeguarding National Security: Basic Law Article 23 Legislation – Public Consultation Document”, Security Bureau, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (January 2024), 11, https://www.sb.gov.hk/eng/bl23/doc/Consultation%20Paper_EN.pdf

42 “What Do UK Hongkongers Want in the Upcoming General Election?”, Vote for Hong Kong 2024 (April 2024), https://www.vote4hk.uk/survey-report

Bibliography

Bagby, Philip. Culture and History: Prolegomena to the Comparative Study of Civilizations. California: University of California Press, 1958.

Carrico, Kevin. Two Systems, Two Countries: A Nationalist Guide to Hong Kong. California: University of California Press, 2022.

Chan, Kinglap. 陳競立. “Hong Kong needs second return”. 香港需要二次回歸. Oriental Daily News (25 June 2020). Accessed 17 June 2024.

Chen, Hao. “Responding to the domestic violence of Hong Kong independence in step with the times”. Journal of the Fujian Institute of Socialism 104, no. 5 (2015): 104-106.

Chin, Wan. On Hong Kong as a City-State. 香港城邦論. Hong Kong: Enrich Publishing, 2011.

“Confucianism, The Analects, Zi Lu, 18”. Chinese Text Project. Accessed 17 June 2024.

Davis, Michael. Making Hong Kong China. Ann Arbor: The Association for Asian Studies, 2020.

Huntington, Samuel. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Kaufman, Alison. “The ‘Century of Humiliation’ and China’s National Narratives” (10 March 2011). Accessed 17 June 2024.

Kissinger, Henry. On China. London: Penguin Books, 2011.

“Legislative Council Official Record of Proceedings”. Hong Kong Legislative Council (19 June 1997).

Mark, Chi-Kwan. “To ‘educate’ Deng Xiaoping in capitalism: Thatcher’s visit to China and the future of Hong Kong in 1982”. Cold War History (2015): 1-20. DOI: 10.1080/14682745.2015.1094058

Page, John. “The East Asian Miracle: Four Lessons for Development Policy”. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, Volume 9 (1994): 219-269.

Pye, Lucian. “Social Science Theories in Search of Chinese Realities”. China Quarterly, 132 (1992): 1161-1170.

“Safeguarding National Security: Basic Law Article 23 Legislation – Public Consultation Document”. Security Bureau, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (January 2024).

Song, Xixiang. “The latest characteristics of the development of the ‘Hong Kong independence’ and the responding strategies”. “港獨”勢力發展的最新特點及其應義策略. Journal of the One Country Two Systems Studies 34, no. 4 (2017): 85-94.

“Standing Firm on Hong Kong’s Core Values”. Hong Kong Great Speeches. Accessed 17 June 2024.

“The Practice of the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ Policy in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region White Paper (Full-text)”. “一國兩制”在香港特別行政區的實踐白皮書(全文). Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR (10 June 2014). Accessed 17 June 2024.

Tsang, Steve. A Modern History of Hong Kong. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 2007.

US-China Forum (16 July 2022). Accessed 17 June 2024. https://www.us- chinaforum.com/27599369133554222727/1210558

Vines, Stephen. Defying the Dragon: Hong Kong and the World’s Largest Dictatorship. London: Hurst & Company, 2021.

Wang, Jianshen 汪建新. “Why did General Secretary Xi emphasize ‘confidence in culture’ in his 1 July speech?”. 习总书记“七一讲话”为何强调“文化自信”? People’s Daily Online (4 July 2016). Accessed 17 June 2024.

Welsh, Frank. A History of Hong Kong. London: Harper Collins, 1993.

“What Do UK Hongkongers Want in the Upcoming General Election?”. Vote for Hong Kong 2024 (April 2024).

“What does Xi Jinping’s China Dream mean?”. BBC News (6 June 2013). Accessed 17 June 2024.

“Xi Jinping: Carrying on from the past to the future, continuing to advance towards the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. 习近平:承前启后 继往开来 继续朝着中华民族伟大复兴目标奋勇前进. Xinhua News (29 November 2012). Accessed 17 June 2024.

Zhang, Wenji. “The Meaning of Hong Kong’s second return”. 香港二次回歸的意義. “‘Only we are Hongkongers in the world’ – A review of the tertiary students’ forum on 1 July”. 「世界上只有我們是香港人」—回顧大專學界七一論壇. University Community Press (2 July 2018). Accessed 17 June 2024.