The 2018 Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in early September – a triennial conference in which the Chinese political leadership meets its counterparts from across Africa – caught the attention of many commentators. Chinese president Xi Jinping’s announcement of $60 billion in aid, investment, and loans for Africa in the next three years has re-opened the debate over the hegemonic role played by China in one of the fastest growing areas of the world.

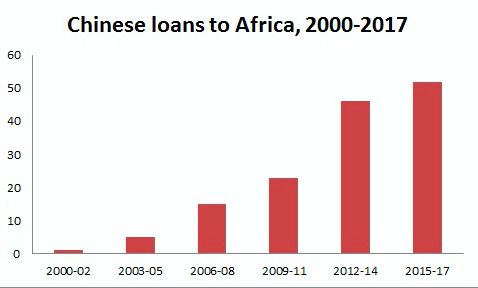

The announcement did not come as a surprise: Beijing had pledged the sum at the last FOCAC summit in 2015. But they point to a striking development in the past two decades: Chinese loans to Africa skyrocketed from about $1 billion in the three-year period 2000-2002 to $52 billion in 2015-2017.

Figure 1: Chinese loans to Africa in US billion between 2000-2017

(source: SAIS-China Africa Research Initiative – SAIS-CARI)

China’s trade with African countries, moreover, has increased forty-fold in the last 20 years, and mining-related investments have jumped more than 25-fold from 2006 to 2015. This massive economic penetration ranges from the telecommunications industry to textile plants, from construction activities to mining hydrocarbons. Attempts to develop Sino-African cooperation date back a generation, to Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

But the pace at which China has transformed itself from being an external supporter of anti-colonialization movements into the preeminent economic partner of several African countries is astonishing. Even because, such a metamorphosis is happening in a historical moment in which the United States, as well as the European Union, seem incapable of playing a similar role.

Until now, in sharp contrast to European strategies of one century ago, Chinese influence in Africa does not take place via military campaigns or colonization. By contrast, pointing to economic and, above all, infrastructural projects Chinese leaders describe their model as a win-win cooperation. Writing in The New York Times Magazine last year, Brook Larmer presented evidence that the benign Chinese face belies a new domination that is not necessarily benevolent, just updated for an era of intense global trade.

Similar concerns have been recently raised by the Italian journalists Milena Gabanelli and Danilo Taino in Corriere della Sera. They view large-scale Chinese infrastructural projects in Europe as a stepping stone to economic penetration and market-making for Chinese goods abroad.

China’s economic interests in Africa are spread unevenly across the map. At the top of the Sino-African cooperation, there are hydrocarbon- and mineral-rich states of Africa where Beijing’s direct investments are largely concentrated. Algeria is the North African country with closest economic ties with China and ranks third overall, just behind South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

As Thierry Pairault astutely observed recently in Chine-Algérie: Une relation singulière en Afrique, it was only after Algeria abandoned official references to socialism in the 1990s that economic and commercial relations between the two countries expanded significantly. For several years, that expansion was curtailed by the long-lasting civil war between the government and an Islamist insurgency.

Once the political temperature of the country went down in the late 1990s, China started promoting its interests in earnest. In 2001, China’s share in Algeria’s foreign trade barely registered. By 2016, however, China had become Algeria’s number one supplier, overtaking France – which had long held that place of primacy for historical and political reasons.

Scholars and journalists have focused on three aspects of the rapid intensification of Sino-Algerian cooperation: China’s foreign direct investment (FDI), infrastructure being built by Chinese companies on Algerian soil, and the arrival of Chinese migrants in the country. These elements are all present to some extent but should not be overstated. The fact that Algeria is one of the main African recipients of Chinese FDI does not automatically mean that the investment has a measurable impact on the Algerian economy.

When Chinese FDI flows are measured using the yardstick of the gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), it becomes clear that Algeria relies very little on FDI to finance its GFCF – around 50% less than the African average – and also that China’s contribution accounts for less than one percent, which is in line with other large countries. Another important element is significant investment in construction by Chinese companies, including the new Ministry of Foreign Affairs building, the new mammoth Grande Mosque of Algiers, and an east-west highway of about 1,200 Km on the Mitiya plateau which employed nearly 13,000 Chinese migrant workers. Despite sensitivities about not employing Algerian labor for these jobs, the total number of officially registered Chinese workers in Algeria has never exceeded 0.2 % of the workforce.

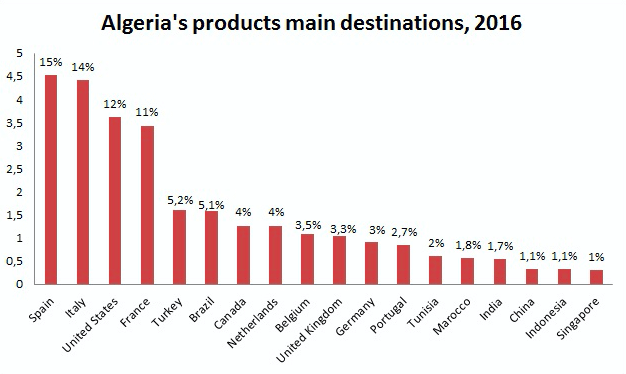

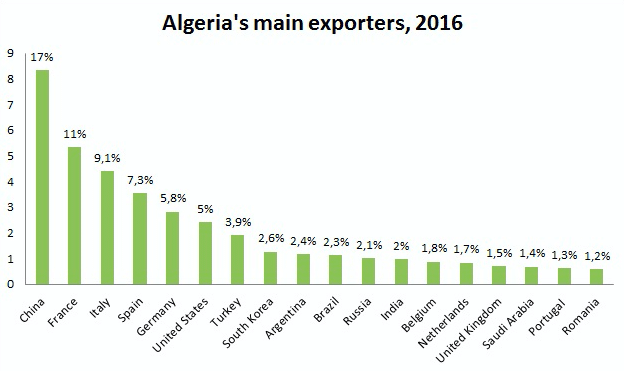

China’s real strength in Algeria derives primarily from a massive surplus in its balance of trade. Whereas Beijing ranks fourteenth among the main importers of Algerian goods (334 million dollars), it is by far the first exporter (8.35 billion dollars). See Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2: Main destinations of Algerian products in US billion and in percentage in 2016

Figure 3: Countries that exported more in Algeria in US billion and in percentage in 2016

Contrary to the widely held notion that China has conquered the world thanks to cheap and easily-made products, about 40 percent of China’s export in Algeria is made up of machinery – that is, the beating heart of the capitalist system. That industrial sector had been dominated by European powers – France, Italy, and Germany in particular – in previous decades. This reveals a paradox regarding European political weakness and internal distrust. Algeria’s economy is almost entirely reliant on hydrocarbon resources.

In 2016, they made up one-third of Algeria’s GDP, two-thirds of all government expenditure, and about 93% of the country’s exports. European countries are key consumers, importing importing nearly all oil- and gas-related products, with Italy leading the pack with an astonishing 96 percent of hydrocarbon-related imports. Imported oil and gas are crucial for resource-poor European countries, but the sale of hydrocarbons to European states is also the strongest suit of Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s regime to keep the Algerian economy afloat and to buy social support.

Until now, this potential leverage on the Algerian government has not been used by European powers as a way of halting the massive Chinese expansion. If the current trend is not reversed, Italy, France, and possibly even Germany, will soon be Algeria’s net importers.

Photo: Lintao Zhang / POOL / AFP