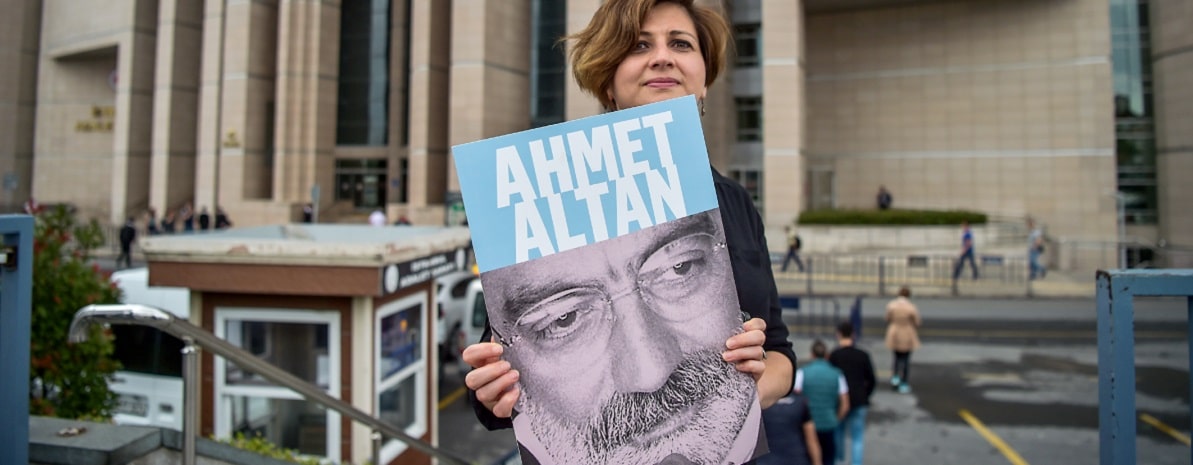

The first aggravated life sentences for journalists since the failed coup of July 15, 2016 have been handed down in Turkey. Nazlı Ilıcak and the brothers Ahmet and Mehmet Altan, whose editorials, programmes and comments have both charted and contributed to the changes seen in Turkey for over 30 years, now face the prospect of spending their remaining days in prison. All three journalists were initially supportive of the reforms introduced by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) after its rise to power in 2002 but have since then become very critical of the regime.

The three journalists were arrested at the end of September 2016 and accused of having taken part in the failed coup as well as of being part of the “media branch of FETÖ (Fetullahçı Terör Örgütü)”, the acronym coined by the Turkish government for the “terrorist organization” loyal to Fethullah Gülen, an imam who has lived in self-imposed exile in the United States since 1999. Once very close to the Turkish government, Gülen is considered by the president and a large section the Turkish public to have been the brains behind the coup attempt. Various journalists who worked for media outlets linked to Gülen, were arrested and charged as terrorists in the wake of the coup. Some fled, while others, including the Altan brothers and Ilicak, were detained.

Prosecutors sought triple aggravated life sentences – the heaviest penalty in the Turkish penal code – for all three journalists, presenting articles, phone taps, witness statements and pronouncements by the journalists themselves on TV programmes as evidence of their crimes. They specifically mentioned a televised talk show that Ahmet Altan had appeared on, a day before July 15 in which he harshly criticised the government. Altan had appeared as the guest of his brother and Ilicak on the Can Erzincan network, which was later closed for being affiliated with Gülen. The prosecutors contended that certain words Altan had spoken on the show were “subliminal messages”, indicating that the brothers “knew” that there would soon be a coup. This was deemed sufficient for them to be arrested.

Before the trial ended, on January 11th, Turkey’s Constitutional Court considered a motion presented by lawyers for Mehmet Altan and Şahin Alpay – another journalist already in prison for 18 months accused of the same crime – stating that the two brothers’ preventive detention violated their constitutional rights. The lawyers argued the two should thus be set free, as had happened in February 2016 at the trial of Can Dündar, former editor-in-chief of the Cumhuriyet newspaper, and the journalist Erdem Gül.

It was an exemplary decision that would not only have prevented imminent intervention in the case by the European Court of Human Rights, but, according to some legal experts, would also have established a precedent for other imprisoned journalists. In any case, local courts refused to carry out the Constitutional Court’s directive, while a government spokesman, Bekir Bozdağ, stated that the court had “overstepped itself,” for the first time going against the country’s judicial hierarchy. Additionally, during their trial, the judges prevented defence lawyers from defending their clients on more than one occasion, expelling them from the court room and preventing Mehmet Altan from reading the Constitutional Court’s decision in their favour.

On Friday, February 17th, the 26th High Criminal Court of Istanbul found Altan Ilıcak and three other defendants guilty of “trying to abolish the constitutional order of the Republic of Turkey” and sentenced them to aggravated life sentences, the heaviest penalty in the Turkish penal code after the death penalty was abolished in 2003 as part of the reforms undertaken by Turkey as part of opening negotiations to join the European Union, and which were signed into law by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. This sentence means solitary confinement for 23 hours a day and strict limits on the right to receive visitors, to make phone calls or mingle with other prisoners.

The sentences attracted a great deal of condemnation, especially abroad. David Kaye, the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, said: “The court decision condemning journalists to life in prison for their work, without presenting substantial proof of their involvement in the coup attempt or ensuring a fair trial, critically threatens journalism and with it the remnants of freedom of expression and media freedom in Turkey.” A similar statement was expressed by Harlem Désir, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, who emphasised that such lack of respect for the legal hierarchy, “raises fundamental questions about the ability of the judiciary to uphold the constitutionally protected right to freedom of expression.”

While the possibility to lodge an appeal for the three journalists remains open, the likelihood of legal success is as uncertain as ever. According to one lawyer, Kerem Altıparmak, the government takes a great risk in defying decisions of the Constitutional Court, for this would indicate that the court is no longer an efficient legal recourse inside the country meaning that appeal petitions from Turkish citizens could potentially legally bypass it, moving straight to the European Court of Human Rights. Commenting on the sentences, one of the defence lawyers, Ergin Cinmen, stated that the only countries signatory to the European Court of Human Rights where Constitutional Court decisions are not being applied are Azerbaijan and Turkey, adding that “this decision shows that justice in Turkey, or at least that part of it that we are experiencing, has become a government tool.”

But judicial independence has been seriously tested also by the sudden release of Deniz Yücel, a correspondent for the German newspaper Die Welt, who was imprisoned for over a year without knowing what he was charged with. He was released the same day the Altan brothers and Nazlı Ilıcak were handed life sentences. Two days before his release, Turkey’s Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım, during a visit to Germany, hinted that there would soon be developments in the case of the German–Turkish journalist. Yücel’s release left a bad taste in many people’s mouths. That same day, prosecutors charged him with terrorist propaganda offences and demanded a sentence of 4 to 18 years in prison, but without forbidding him from leaving the country. All this was the outcome of diplomatic traffic between Ankara and Berlin that, according to the German press, took place behind closed doors during the visit to Rome at the beginning of February by Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Germany’s Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel, and later in Turkey. In January, Gabriel considered the possibility of resuming arms sales to Turkey should Yücel be set free.

Translated by Francesca Simmons

Credit: Ozan Kose / AFP