Germany is not immune to the phenomenon of religious radicalism. Over the past six years, about one thousand foreign fighters have left Merkel’s country for Syria and Iraq to join ISIS and other terrorist groups. This has also happened in various other Western European countries, from France to Belgium, from the Netherlands to Great Britain, mainly affecting societies in which the integration of second and third generation immigrants has proved to be particularly complex. The German case, however, presents particular, distinctive characteristics on top of those that may be occurring elsewhere, making its society a unique case study. Compared to other European nations, Germany has seen a far higher number of its citizens, with no migratory origins to their name, being converted to radical Salafi Islam. Over several decades, the country has experienced massive immigration into particular, well-defined geographical areas of its territory – entire regions of its East, for example, have been untouched by immigration – in which radical groups have been able to find fertile soil in the country, without any particular opposition by the authorities. Their ability to be visible in the country and to distribute propaganda material on the streets is something that is forbidden by French secularism, for example. The very delicate relationship that public opinion has with its own past has resulted in the institutions preferring not to impose any forms of strong national identity on new generations of Germans and immigrants. In this context, radical groups have had plenty of time and space to canvass publicly in a structured and organised manner. A number of initiatives led by Salafi groups, named ‘read’ (laws) and ‘Die wahre Religion’ (the true religion), have distributed thousands of copies of the Koran and other related material. With the coming of the so-called Arab Spring, many militants belonging to these groups left the country to fight in Syria and in Iraq. At this point, the German authorities intervened by criminalizing such acts, charging and arresting some of their leaders. In spite of this, some members, at least those left in Germany, regrouped and resumed their propaganda activities also concentrating on refugees.

These developments have been closely followed by Thomas Muecke, a member of the Violence Prevention Network , a team of experts that, since 2001, has encouraged the prevention of ideological and religious extremism. In more recent years, Muecke has been intensely involved in preventing the spread of radical Islam among young Germans, following particularly delicate cases, sponsoring de-radicalisation programmes for those who have already joined certain groups and, more recently, the managing of the escape and consequent repatriation of the foreign fighters who decide to abandon the battlefield and return to Germany.

Doctor Muecke, when did you begin to notice the presence of radical Islam in Germany?

During the past six or seven years we started to see many young men and women leave for war zones, primarily Syria, as well as the presence in Germany of extremist groups using the Muslim religion as a means of diffusing propaganda amongst the young so as to achieve their own ideological objectives. Before then, there had not been any significant cases, although there had already been problems linked to immigration and integration. Part of the population with a history of migration did not feel included in society and, as time passed, indicated that this phenomenon was being caused by a lack of integration, precisely as a result of their being Muslim. In recent years, however, there have been major changes only vaguely correlated to those pre-existing issues. People with no migratory history began to convert, pledging their allegiance not to the religion, but to extremism.

The number of those with no history of migration converting to Islam in Germany is proportionally far higher than in other European countries. Why is that?

Germany is paying the price for never having developed a German Islam. For some time now, there have been various attempts to influence the development of Islam in Europe and Germany from abroad. Countries such as Saudi Arabia, along with others, have played a significant role in exporting their own concept of religion. What was lacking in Germany was the development of an Islam independent from foreign influence. Communities of Muslims who offer religious services to believers, while often remaining linked to the governments in their countries of origin, have existed for decades. This applies, for example to Germany’s largest Muslim organisation, the DITIB, The Turkish-Islamic Union for the Orientation of Religion, which, according to an agreement signed decades ago between Berlin and Ankara, is funded directly by the Turkish government’s Ministry for Religious Affairs. Their imams are sent directly from Turkey and rotate every five years. Sadly this is a widespread tendency. These imams almost always come from abroad, they were not trained here and have never been members of a society with which they never really come into contact. This has contributed to creating a discrepancy within the Muslim community, whose leaders struggle to reach out to young people who were born and raised here and express religious and spiritual needs. The Salafites have taken hold of this generational clash and have been able to speak to the young using their linguistic codes.

Which are the most active and successful groups in Germany?

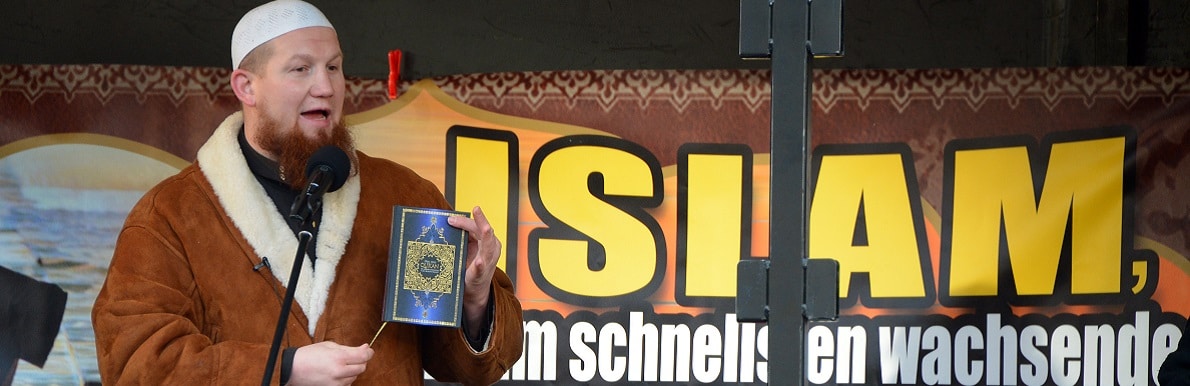

The most dangerous movement is Salafi extremism, which endorses the idea that the law of God is the only law that truly applies, rejecting everything that Islam has produced after the first three generations following the Prophet Mohammed. Democracy is not part of their vision of the world and that is why they focus on revolutionising society, beginning by imposing their own programme. Salafites are divided between those who are openly violent and want to change society by waging a holy war and those who are political. It is the political branch that has grown the most in recent years. In Germany there are about 10,000 known active militants promoting their vision of the world through incessant recruiting and indoctrination activities. It is they who are responsible for the fact that about 1,000 young men and women have left the country to join terrorist groups in war zones.

Political Salafites say they have nothing to do with those who are openly violent and with terrorists. Is there a clear dividing line between them?

The dividing line between political and armed Salafism is a very fine one. The leader of the political branch is called Pierre Vogel and he is a clearly an extremist religious fundamentalist. Everyone is free to live in a fundamentalist manner, however, when one tries to change society by imposing one’s own principles, one becomes an extremist. We have seen that many of the men surrounding him have moved on to armed Salafism. He himself acknowledges that many of the young boys associated to him, to whom he was preacher, have left to fight in Syria. As far as violence is concerned, Vogel is assuming a tactical stand. When there was an attack in France, he distanced himself from it, saying that those belonging to ISIS do not understand how Europeans think and that, in terms of usefulness, terrorist attacks in Europe achieve nothing. It is an assessment coldly based on a utilitarian calculation.

What are their objectives? What kind of society do the Salafites want to create in Germany and in Europe?

The final objective is that of creating a homogeneous society in which anyone dissenting from them is defined as an ‘infidel’ and therefore loses the right to exist. Just as right-wing extremists propose a homogeneity based on race, the Salafites’ base theirs on religion. Ultimately, this would result in the abolition of democracy, human rights and diversity.

What, in your opinion, is their strategy in Germany and in Europe for achieving these objectives? Is it possible that they will achieve them, as they say, without resorting to violence?

No. Theirs is not a religion but an extremist ideology that uses religion instrumentally to achieve its objectives. They could never achieve this in Germany without violent reactions. Our constitutional principles, based on democracy and human rights, are unchangeable and if they are questioned, the only means available for changing them is through violence.

How are these groups funded?

That is known to the security services and I don’t believe they wish it to be made public. What we know is that they have a great deal of money available to them. Some of them work organising pilgrimages to Mecca, which brings in money, but is also useful for recruiting pilgrims locally. On these journeys, involving a powerful spiritual participation, pilgrims are quickly recruited to their cause.

You work with many people in Germany who have converted in recent years and have been recruited by the Salafites. Are there shared characteristics among them?

No, it can potentially happen to anyone. So far I have worked with 350 people who have been radicalised in Germany, some of whom travelled to war zones and then eventually came back home. Every story is unique and unrepeatable. They involve immigrants and Germans, people of every social and economic background and not all of them coming from necessarily unstable environments. There is no hard core of analogous reasons. Overall, one can, however, say that they are often young men recruited by others who play on their emotions. These are young people who had nothing to do with any sort of religion prior to having converted.

After being approached by these other people and listen to their stories of a ‘true Islam’, they are left entranced by it without even knowing of the heterogeneity that characterises this religion. They do not enter the world of the Salafites already radicalised; the process happens once they are in it. All young men experience certain periods during which they look for direction, some also experiencing real crises. It is at that point that these extremist groups intervene, providing answers to their existential questions and making them feel as part of a group. I worked, for example, with one family in which the father was an activist for PEGIDA (acronym for Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West, a political movement deeply rooted most of all in the territories of former East Germany Editor’s note) who hated Muslims. After quarrelling with his 14-year-old daughter for typical reasons, she joined the Salafites out of revenge. In another case, a 17-year-old girl lost her father, the most important person in her life. She was approached at school by a Salafi group that comforted her and persuaded her to join their dialogue group. She attended it without even knowing who the Salafites were and two months later she left the country with them.

German Salafite leaders admit that many of the young people they have recruited have gone to fight in Syria. They do however state that those who leave abandon the group before their departure. Is that true? Or is there another organisation behind all this to which all these groups are linked?

The process can be retraced with a degree of precision. The first step used by the Salafites to approach the young people is the distribution of copies of the Koran on the streets. A young man does not usually approach the stands where these books are distributed of his own accord. It almost always happens through a friend, maybe someone attending the same school, who says, “Come and meet my brothers.” Together they approach the stand where the books are and where they find very kind people who provide unexpected acknowledgement and warmth. These people do not discuss matters, they simply tell them to “read” (Lies), then inviting the person to come and have a talk in private rooms. What happens is these private contexts is decisive. The young person experiences an amazing sense of belonging and feels immense emotional closeness. There is no talk of who-knows-what terrible ideology, but one lives in a community, the ummah. Everyone cooks together and plays soccer together. Then, little by little, the young man starts to be told that in this society Muslims are alienated and oppressed; he is shown scientific surveys, according to which Muslims have greater problems in accessing the labour market and finding a home. The message conveyed is that Muslims are discriminated against everywhere, defining an identity of collective victims, and then certain phrases are used such as “Islam and democracy are not reconcilable” and “as a Muslim, there is nothing for me in Germany.” What happens during this phase is something very profound; the young person is suddenly made extraneous (entfremdet) to the society in which he was born and grew up in. This is no longer his home, no longer his homeland. This is the first form of eradication. The second phase occurs when he/she is told that this beautiful way of life, Islam, must be also brought to other people, beginning from the family environment. Suddenly these young people find themselves confronting their parents, demanding they convert to and embrace true Islam. Initially the parents are frightened and no longer recognise their own children. If, as it usually happens, the parents are not persuaded, they too are considered as infidels. The result is that one is alienated from one’s own parents. This then extends to all previous social contacts, from the soccer team to one’s group of friends. At this point the young person is left to this group of people with similar ideas, like a sect, and no longer accepts anything that differs from it. I was once told by a person close to ISIS, “I would kiss your feet if you cut off my father’s head because he does not pray regularly.” This sentence indicates how profound this alienation is. Then, at a certain point, these young people are shown terrible films depicting how Muslims are killed, raped and tortured. Videos of the terrible crimes committed by Assad are used to play on the moral values that all young men have, saying that these crimes were not committed strictly by Assad’s men but by infidels in general. At that point certain words are spoken, such as, “how can you sleep in a warm bed here in Germany while elsewhere your brothers and sisters are killed and raped?” This has an effect. The young person feels it is his/her duty to do something. At that point, in an apparently spontaneous manner, they decide to embark on a journey abroad. That is what the preachers were waiting for. At that moment the young man finds everything in order to leave immediately. Everything is organised extremely well from a logistical point of view and for a long time it was extremely easy to quickly reach the war zones. Once that level of persuasion has been reached it is almost always too late to persuade them to take a step back.

How did they get to Syria?

It is usually through Turkey, as the border with Syria was open. All it took was a flight to Istanbul followed by a bus or a taxi to a border city. The border is then crossed on foot until one is picked up by the al-Nusra or by ISIS men waiting on the other side. The entire system was perfectly organised and there were never any problems. Some young men told me that the traffickers who accompanied them in Turkey told them that “If you hear shooting as you cross the border, don’t worry, it is just Turkish soldiers, but they are just shooting in the air.” We have also heard that some of these boys who returned from Syria to Turkey were stopped and questioned by the Turkish authorities, who told them that they were better off not returning to Germany and that should not tell anyone what they had seen, confirming the fact that part of the Turkish institutions would have preferred that these young men had not returned to Germany. Things are changing now as the geopolitical agenda is changing. Turkish interests are no longer about weakening Assad, as they have been for a long time.

What made many of these youngsters regret the choice they had made and decide to come back?

The reality check usually occurs when the young convert finds himself at a training camp in Syria. When one enters such a place, one is immediately detained; one must hand in one’s passport. The system is very rigid and they also have a very strict internal judicial system. One can hear the screams of those being tortured. There have been situations in which someone accused of being a traitor is beheaded and the body then placed on a cot with the head on top of it and paraded throughout the camp. From the very start it is very clear what will happen to those who do not cooperate. They can ask no questions nor express any doubts without risking their lives.

How did some of them manage to return home?

Fleeing is dangerous. In some cases, some young men managed to keep in touch by phone with their parents, who in turn put us in direct contact with them. In one case, a boy had been selected for a suicide attack. There was a bus that regularly came to pick up those destined to carry out suicide attacks and so as to avoid it this boy always went to the back of the queue, waiting for the bus to be full so as to be sent back the next time. It was as a result of this that he decided to leave. I cannot provide the details of the manner in which he and others left, but the process involves fleeing very quickly towards the Turkish border. In some cases parents have travelled to war zones to bring home their children, which is very dangerous and not advisable. If they do go, however, we look after them and advise them. Although we are not present on the ground, we prepare every step of their escape, including their return to Germany in coordination with German authorities.

What happens to the young men who return to Germany?

The young man suddenly finds himself sitting opposite us, with his father to his left and his mother to his right, both of whom having feared for his life for months. Of course the father asks “how could you have done this?”. Filled with shame, the boy sits in silence and looks at the floor, now aware of what he has done to his family. The father continues to ask, “Why? Why? Why?” and the son is really unable to answer. There are no answers, he does not realise what has happened. It takes us weeks or months of talks before he manages to understand why he made the decision. This allows me to understand the extent to which the Salafi world is manipulative and their level of expertise they in manipulation techniques. If one watches Pierre Vogel’s videos on line, one can see how he uses specific communication techniques in his speeches and how he tries to get people to become attached to him. Even his emotional exclamations are staged and not authentic. These are scenes that have an effect on young men.

Is there a risk that these returning former fighters will want to continue to pursue their radicalised paths here in Germany?

Yes, of course. There are some who return and are confused and ask themselves, “Is what I have seen really Islam?” These people generally look for a debate in order to find answers and it is very important that they should have an interlocutor. Others instead remain silent and do not express their ideology. It is hard to know how many of them there are. There are some who would only like a new beginning, while others remain silent, waiting to return to the battlefield. That is the greatest danger.

Can you confirm the existence of a return strategy for foreign fighters, so as to be able to attack Germany and Europe?

Germany and Europe can be attacked at any time. ISIS and those who share its ideology think globally. It is an international movement that does not acknowledge borders. We once met a boy who had just come back, he was in prison and depressed. He had abandoned ISIS and therefore felt he had betrayed Islam and was certain that within two or three weeks they would behead him. Astonished, we asked him who would behead him? He answered that it would be the ISIS soldiers who would soon have conquered Germany. When we made him understand that this would not happen, he continued to be convinced that he would die anyway for having betrayed Islam. Our societies are vulnerable. It is far easier to carry out attacks than it was 20 years ago, when a degree of logistic preparation was needed. If there are men persuaded to damage society, they are nowadays able to do so. How will a society in constant danger of being attacked evolve? How will citizens live in this constant climate of insecurity? The German Salafites are just 10,000 out of 80 million inhabitants, and yet they are able to cause fear. That is what the terrorists want.

The Salafites openly spread their propaganda among the young refugees who have arrived in Germany in recent years. Eighty percent of the Syrians who have arrived say they did not flee ISIS or the rebels but Bashar al-Assad’s shelling. The Salafis say that the minority fleeing ISIS want nothing to do with them because they would identify them with the crimes they have seen committed by terrorists. Others, however, would have no problems with them, also in view of the fact that they share the same beliefs. Have you any evidence of a rise in the number of Salafites linked to the arrival of refugees?

Yes although, for the time being, only 10 percent of radicalisation cases we have worked on have involved refugees. In most cases the people involved were born and raised in Germany. In spite of this, we have seen a great increase in contact between refugees and the Salafi world. The shared belonging to Sunni Islam allows for common ground to be found. Those fleeing Assad’s regime have often suffered the same brutality and barbarisms as those inflicted by ISIS and feel close to all those who have opposed Assad, because they have not personally experienced ISIS. This is why the Salafis try and use this to achieve their own objectives and therefore the spread of the Salafites’ intense propaganda activity among refugees is understandable. Those who arrive are usually Muslims and they look around to find places in which they can fulfil their religious duties. That is how contact with the Salafites is established. Those fleeing ISIS don’t want to have anything to do with the Salafites; the others are uninformed. If integration does not work, the refugees risk becoming easy prey for recruiters.

How do you intervene when you see a case involving the radicalisation of a refugee?

We intervene through a colleague who speaks their language, an element that establishes a common ground in and of itself. What is particularly problematic is the arrival of refugees who have experienced war and have been traumatised by it. Many are unaccompanied minors who suddenly find the Salafites offering them a community that will welcome them. At that point they feel they belong to something and listen to everything they are told. When we see cases in which a refugee wants to go to mosque and pray at all costs because if he doesn’t, he says, he will go to hell, it becomes clear to us what sort of people he has been in contact with and so we intervene immediately. We try and provide these boys with alternatives so they meet other kinds of people and are freed of the dependency relationship they have established. We want them to listen to various opinions and know that it is acceptable to ask questions. We are seeing that untreated traumas caused by war can lead one to very quickly turn to extremists. There are some who have lost the will to live and for this reason they join the Salafites. In 2017 we still have people in Germany who want to return to Syria to fight, which essentially implies a death sentence.

Are there still people leaving for Syria regardless of ISIS’ war now being lost?

Yes. These are men who no longer wish to live in this society. People who want to fight to the death. It is hard to accept, just as it is hard to accept that a young German woman should decide to travel to a war zone to be stoned because she is no longer a virgin. These are people who have lost the will to live.

Dr. Muecke, for obvious historical reasons, Germany does not want to provide a strong German identity for migrants and the new generations to identify with. What social solution could there be for addressing the situation you have described to us?

In Germany, as in other European countries, we need autonomous religious communities that freely provide religious services so that people can live with their own beliefs without running the risk of coming across people who want to exploit their faith. We also need a strong political education on democracy and human rights in schools. These are the principles upon which our shared identity is based. We must avoid extremists becoming the only interlocutors for the young. One must then analyse the strategies used by terrorists and extremists. ISIS’s strategy, which has worked so far, is not restricted to Syria and Iraq, but is global and oriented against the West and against democracy. The intent of the attacks is not the deaths per se, but the reactions they generate. They want to create resentment against society’s minority, Muslims, so they can try and recruit as many people as possible among them. They have two enemies; on the one hand an external enemy, the decadent West, and on the other an internal one, those members of the Muslim community who do not side with them. Nowadays, German society is afraid and that was the objective that the terrorists have achieved. If one wants to do something, one must be careful not to contribute to widening this rift and this polarisation.

Translated by Francesca Simmons