The General National Congress (GNC) elections were part of the constitutional declaration announced by the National Transitional Council (NTC) in August 2011, later amended three times. The repeated amendments reflected the pre-election atmosphere in Libya post-Gaddafi, where the political landscape underwent radical reshaping, highlighted decentralized local forces like regional councils and armed militias, including jihadist groups and federal movements. Initially united against Gaddafi, these forces evolved into entities vying for power and resources, often disrupting the political scene to secure their interests.

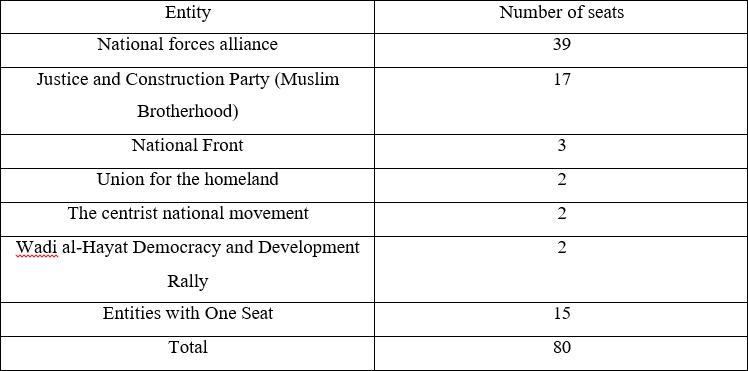

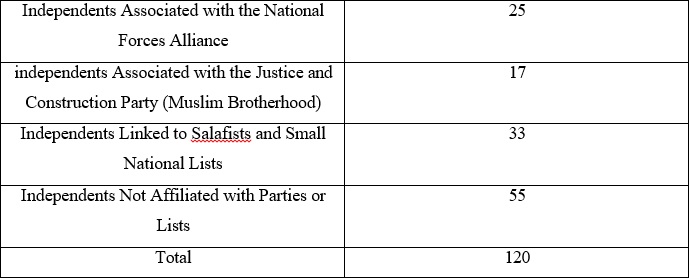

The GNC elections produced a fragile political landscape. The National Forces Alliance (NFA), led by Mahmoud Jibril, secured most of the political entities’ seats (39 out of 80), trailed by the Justice and Construction Party (JCP), representing the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood (17 seats). A smaller cluster of parties with varied affiliations claimed 24 seats, while 120 members secured seats reserved for independents.

Polarization among political parties within the GNC peaked with the issuance of the Political Isolation Law in May 2013. This law aimed to ban political activity by individuals who held prominent civilian or military positions in the Gaddafi regime. The ban was later extended to anyone associated with organizations or institutions during that period.

In 2014, the Libyan political process collapsed when the GNC extended its term, which was supposed to end in February 2014, and refused to relinquish power to the House of Representatives (HOR), which was elected on June 25, 2014. The elections of HOR were seen as disappointing by the Islamists and their allies, who had nearly complete control over the GNC. This led to a legitimacy crisis that escalated into a comprehensive civil war, causing political and administrative divisions throughout Libya.

Paving the way for the elections

During the pre-election period, various political tensions emerged, which the NTC attempted to contain through a policy of appeasement. For instance, when faced with criticism from Islamists regarding the women’s quota, the NTC retracted its proposal to allocate 10 percent of the seats to women and instead opted for party lists that included both male and female candidates in rotation.

Furthermore, the allocation of seats to independents and party lists has caused confusion for the NTC. Jason Pack and Haley Cook observed that the Brotherhood preferred to increase party list seats, anticipating electoral success. Conversely, parties suspicious of Islamists feared that increasing the number of seats allocated to parties would lead to Islamist dominance.

In continuation of its appeasement policy, the NTC announced a new amendment to Article 30 on July 5, 2012, amid fears of electoral disruption. Parties linked to federalists Cyrenaica had attempted to sabotage the elections by destroying electoral offices in Tobruk and Benghazi, burning ballot material warehouses in Ajdabiya, and closing five oil valves with gunmen from the Cyrenaica Regional Council. Initially, the NTC ignored demands for an equal distribution of GNC seats among Libya’s three regions. However, to protect the electoral process, NTC ultimately amended the Constitutional Declaration. This effort ensured that violations affecting polling stations did not exceed 6 percent in 1,500 different locations.

Electoral seats were allocated based on Libya’s 2006 population census of 5.3 million, with one seat for every 27,000 citizens. Seats were geographically distributed among four regions: the western region received 100 seats, the eastern region 60, the southern region 31, and the central region 9, resulting in a total of 13 electoral districts. The electoral system adopted a mixed approach, combining the majority system for individual lists and proportional representation for political entities with a single non-transferable vote system based on the first-past-the-post rule, not requiring a minimum number of votes to win a seat.

The relative majority system for individual voting highlighted two key issues: First, the significant disparity between winning candidates’ vote counts. For example, the least-winning candidate received 276 votes in Tazerbu, while another won with 40,207 votes in Benghazi. Additionally, 13 candidates won with over 1,000 votes, while 50 others won with fewer than 3,000 votes. Second, most winning candidates received less than 20 percent of the total vote.

The electoral and voting systems contributed to giving a more local and personal character to the political process. This is evident in the allocation of most seats to independents (120 seats), as well as to small political entities. Most small entities were established in marginalized rural areas and won through promises to achieve development and improve living services. Apart from the independents allied with the major political entities before the elections, the rest of the members have become vulnerable to polarization between the major conflicting political entities within the GNC since the announcement of the election results on July 7, 2012.

Critical remarks on the interpretations of the GNC’S election results

The results of the GNC elections reflected the electoral system adopted by the NTC, which aimed to prevent major political entities from monopolizing power. In theory, these steps were intended to strengthen consensus on key issues such as the formation of a new government and the drafting of a new constitution. However, in practice, they strengthened the dominance of local, personal, and regional politics over national politics.

Table No. (1) (Entities Lists)

Table No. (2) Independents

The results of the elections led some media outlets and political observers to misinterpret the NFA’s victory in party lists as a victory for liberals and secularists over Islamists. These claims gained traction when they were used to argue that Libya stood out as an exception among cases of the “Arab Spring,” where Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Ennahda in Tunisia experienced electoral success.

These interpretations were misleading for three reasons: first, the real victory in terms of numerical majority was achieved by independents (120 seats), motivated primarily by local politics or personal ambitions, and it was not yet known whether they were linked to one of the major political entities before the elections. Second, the term “liberal,” as understood in its Western context, applies to only a few members of the NFA or independents associated with it. NFA leader Mahmoud Jibril announced immediately after the elections that the NFA is not secular or liberal but focuses on economic reform and development. This indicates that the appeal of the NFA was based on its development agenda and not on an ideological position against Islam or local conservative culture. Third, the seats obtained by the Islamists and their independent allies and small lists are equal to or greater than those obtained by the NFA and its allies.

The previous observations emphasize the importance of highlighting the local nature of the political conflict, which created new divisions within the GNC based on how the major entities dealt with regions, tribes, and individuals who supported the Gaddafi regime, intertwined with the media-fabricated Islamist liberal division, which Islamists exploited politically, especially at the level of political discourse.

Major political entities

National force alliance

The NFA emerged as an electoral coalition rather than a traditional political party. It comprised approximately 44 political organizations and 236 civil society organizations. Although its former leader, Jibril, had maintained good relations with the Gaddafi regime in the last decade of its rule, he defected during the 2011 uprising. Subsequently, he became a political leader in the NTC, serving as head of its executive office from March to October 2011.

The NFA also included several Libyan businessmen and technocrats who attempted to play reformist roles during Gaddafi’s rule. The most prominent among them was Abdul Majeed Maligta, a businessman from Zintan who, despite his ties to the former regime, formed an armed militia during the uprising and played a key role in taking control of Tripoli in August 2011. Additionally, the NFA was joined by younger figures and more middle-class urban notables in major cities such as Tripoli and Benghazi.

As part of its electoral campaign strategy, the NFA presented its weaker candidates in cities where Jibril was popular, while focusing on Jibril’s personality and development projects in rural interior areas where he was less known. Due to the absence of exiled opposition figures within the NFA, socially popular figures without political backgrounds were attracted to the NFA, such as football player Ahmed bin Suwayd in Benghazi and Sufi cleric Abdul Latif al-Muhalhal in Tripoli. Additionally, the moderate approach taken by the NFA towards social forces loyal to the former regime in cities such as Sirte, Bani Walid, Al-Azizia, Tarhuna, and southern Fezzan helped expand its popular base.

Islamists

Justice and construction party (Muslim brotherhood):

The JCP was established on March 3, 2012, as a political party with an Islamic reference. It included figures who had engaged in reconciliation with the former regime, particularly through the program of de-radicalization led by Saif al-Islam Gaddafi. The party emphasized its openness to all Libyans, not just Brotherhood members. To counter accusations of ties to international organizations, it stressed its independence from other regional Muslim Brotherhood groups, especially in Egypt.

Before the uprising, the Brotherhood was banned in Libya. During the uprising against Gaddafi, they created relief and media organizations, most notably Nidaa al-Khair, to establish financial links between Libya and the wealthy Gulf states that supported the NTC. These institutions have become tools for the Brotherhood to strengthen its presence in society, alongside media platforms such as the Libya Youth Platform and Al-Manara Publications, which are used to convey their messages to Libyan society.

The Brotherhood enjoyed significant political influence within the NTC, estimated to have between 12 and 15 representatives, although none officially declared affiliation. Some members, like Abdullah Shamiya and Salem Al-Sheikhi, held ministerial positions in Jibril’s government. Their influence extended to subsequent governments, with Lamin Belhaj leading the Election Laws Committee and Nasser Al-Manaa serving as the official spokesperson for Abdel Rahim Al- Keib’s transitional government.

Although, Brotherhood did not acknowledge the existence of military arms affiliated with it during the uprising, but some of its members organized fighting brigades, notably Fawzi Bukatf, an oil engineer and Brotherhood member, briefly served as Deputy Minister of Defense before leading two major militias in eastern Libya: the February 17 Brigade and the Rafallah al-Sahati militia.

Salafists

Lacking unified political leadership and being ideologically hostile to party democracy, the Salafists have not established major political entities. However, they have pragmatically joined the elections through party lists or independently. Estimates indicate that their numbers ranged from 25 to 27 members within the GNC.

Within the GNC, Salafists were not a unified bloc but were divided into various parliamentary blocs. One significant bloc, aligned with the Al-Asala rally and close to Grand Mufti Sheikh Al- Sadiq Al-Gharyani, secured 8 of Tripoli’s 14 seats allocated for independents. Another bloc, associated with the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, included Salafists known for their armed activities during the uprising, like Abdel Wahab Al-Qayed. Additionally, 5 independents were tied to the Al-Watan Party led by Abdul-Hakim Belhaj, a former leader of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group. Other suspected Salafists, including militia leaders like MPs Muhammad al- Kilani and Mustafa al-Triki, lacked clear affiliations.

Despite losing most party list seats to the NFA, the Islamists demonstrated strong cohesion within the GNC, particularly among independents associated with them, who exhibited greater loyalty compared to those aligned with the NFA. Islamists have leveraged their relationship with successive governments to build organizational capabilities and expand their political influence beyond their actual popularity in Libyan society. Economic resources and foreign support during the uprising also contributed to strengthening their influence. Furthermore, their success in recruiting military militias provided them with influence on the ground, enabling them to achieve military objectives when political means failed.

Exclusion and Post-Election Conflict (2012-2014): Revisiting Resolution No. 7 and Political Isolation

In accordance with the new conflict dynamics, the Islamists formed an expanded alliance with some former opposition figures in exile and other members from cities and regions considered strongholds of the armed rebellion against Gaddafi. This coalition adopted a radical political stance against social groups associated with the previous regime. In contrast, the NFA took a more moderate stance toward groups associated with the Gaddafi regime as part of its electoral strategy to expand its popular base.

Resolution No. 7

In October 2012, Islamists and their allies pressed for a military operation against Bani-Walid, claiming it hosted dangerous elements loyal to Gaddafi. Tensions escalated when militants from Bani-Walid took hostages from Misrata, including a fighter who had captured Gaddafi and later died after being kidnapped. The incident prompted GNC members, led by Abdul Rahman Al-Suwaihli from Misrata and head of the Union for the Nation Party, along with other members, to pressure the GNC to pass Resolution No. 7. This resolution authorized Libya Shield militias from Misrata and Al-Zawiya to attack Bani-Walid, resulting in the displacement of thousands of civilians and the looting and destruction of many buildings in the city.

Resolution No. 7 passed with 65 votes in favor, 7 against, and 55 abstentions, amid the absence of over a third of members who avoided voting. Despite the weak support within the GNC for the resolution, its passage would not have succeeded without the presence of a military force politically allied with the Islamists.

Resolution No. 7 marked the beginning of the use of armed militias in the political conflict within the GNC. It also led to the increased legitimization of armed militias, formally linking them to the Ministries of Defense and Interior and granting them recruitment and conscription powers based on politicized patronage criteria.

Political isolation law

On December 24, 2012, the Islamists and their allies drafted an initial proposal for the political isolation law with the aim of expanding its scope outside the General National Congress to include former workers in various institutions, companies, and even the judiciary. Two days later, the GNC voted on a proposal to adopt the law and appoint a special committee of legal experts and members of the GNC to draft it. Despite receiving majority support with 125 votes within the GNC, the NFA strongly opposed the proposed law.

In January 2013, the Islamist Abdel-Wahab al-Qayed formed the parliamentary “Loyalty to the Blood of the Martyrs” bloc, which consisted of about 60 members, most of them from the Brotherhood and Salafists. Conversely, in March 2013, the NFA established the “Ya Biladi” bloc, in alliance with independents estimated to number approximately 20 to 40 members. The formation of these parliamentary blocs indicates a new phase of polarization among Libyan political entities.

On April 29 and 30, 2013, military militias from Misrata, in collaboration with militias from Tripoli, Al-Zawiya, and other cities, surrounded the Ministries of Justice and Foreign Affairs to compel the GNC and the government to enact the political isolation law. The siege on the ministries underscored the impression that the law’s adoption would largely be enforced through coercion, raising questions about its final form and scope.

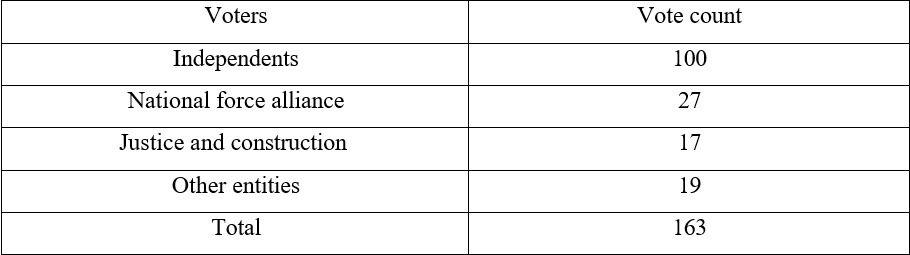

Table No. (3): Voters in favor of the political isolation law and their vote count

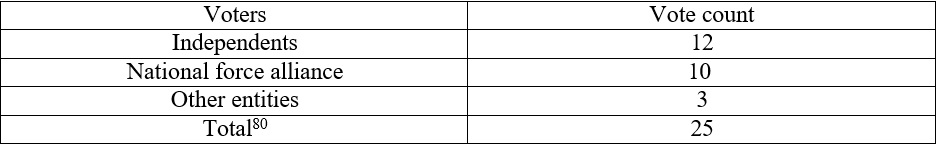

Table No. (4): Voters against the political isolation law

Article 1 of the Political Isolation Law was so extreme that it was impractical to implement. The final version did not differentiate between a person’s position and their behavior. Most of those targeted were civil servants, with only some holding high positions during Gaddafi’s 42- year regime. Given that the state was the primary source of income for most citizens, the voting results clearly showed a major contradiction.

The voting results revealed the consistency of the Islamists and their allies in serving their agendas and programs. The approval of the isolation law also reflected the Islamists’ skill in recruiting military militias as a tool of strategic pressure. On the other hand, the voting results highlighted a significant contradiction in the voting behavior of the NFA, as 27 of its members voted in favor of approving the law despite its clear intention to exclude most of its leadership, including Jibril. The results confirm the assumption that the NFA, despite its high popularity and obtaining the largest number of seats on party lists in the GNC, showed significant weakness in directing the votes of its members due to its lack of party cohesion based on solid ideological or class foundations.

The enactment of the law marked a major shift in the Libyan political scene, significantly tipping the balance of power in favor of the Islamists and their allies. GNC President Al-Magarif resigned, leading to the appointment of Nouri Abu-Sahmain, an Amazigh MP from the Loyalty to the Blood of Martyrs bloc, as President of the GNC.

Abu Sahmain, as ‘Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces,’ financed the creation of the Libya Revolutionary Operations Chamber militia, aligned with the Islamists. Additionally, he established the “Integrity and Reform Commission in the Libyan Army” to enforce political isolation among former officers, resulting in retirements by late 2013.

Amid increasing exclusionary politics, marginalized factions, including the NFA, Zintani militias, former regime loyalists, federalists, and army officers led by Haftar, intensified their criticism of the GNC. As Islamists and their allies imposed Resolution No. 7 and the Political Isolation Law through military coercion, other factions began resorting to violence to achieve their agendas.

On February 14, 2014, Military Commander Khalifa Haftar declared a freeze on the National Conference and the Constitutional Declaration, proposing a temporary presidential body led by the Supreme Counsel for the Judiciary. Initially met with skepticism due to his lack of military power, Haftar later amassed a significant military force comprising former army personnel, and tribal, federal, and Salafist forces. Concurrently, on February 18, 2014, the Al-Qaqaa and Al- Sawaiq militias from Zintan, allied with the NFA, issued a statement giving the GNC five hours to cede power and warning of prosecution if ignored.

Amid escalating military threats and the government’s inability to resolve the oil port crisis, Libya descended into a full-scale civil war, sparked by Haftar’s launch of the “Dignity” military operation on May 16, 2014. Primarily targeting armed militias aligned with revolutionary and Islamic factions in Benghazi, including jihadist groups like Ansar al-Sharia, these forces were politically allied with the entities controlling the GNC.

Haftar’s military operation in the east and the Zintan militias’ movements in the west sparked Operation Libya Dawn as a preemptive measure against Operation Dignity spreading westward. Before the newly elected HOR could take its oath, Libya Dawn militias attacked Tripoli on July 13, 2014, targeting Tripoli International Airport and adjacent camps held by Zintan militias. By the end of August 2014, Libya Dawn had established control over Tripoli.

The HOR convened its inaugural session on August 5, 2014, in Tobruk. This relocation was due to the refusal of the GNC to relinquish power to HOR. Simultaneously, on August 25, 2014, some former GNC members reconvened and established a parallel administration, exacerbating the ongoing political and administrative divide. Subsequently, Libya has been engulfed in armed conflict between two factions, each with its own political, military, and foreign supporters, with the divide persisting to date.

Conclusion

Nearly twelve years after the GNC elections, this paper challenges media interpretations that portrayed the results as a victory for liberals and seculars over Islamists by highlighting the influence of local and personal interests in Libyan politics. The political scene was drawn along new fault lines that went beyond the media-fabricated Islamist/liberal dichotomy, forming two new camps. One camp sought to monopolize all the gains of the February 17 uprising for itself, while the other considered itself an actual or potential loser because of it. The imposition of laws such as Resolution No. 7 and political isolation under the threat of armed militias pushed anti- Islamist parties to resort to armed violence to avoid exclusion. This also contributed to the formation of temporary political alliances that have nothing in common except the interest of remaining on the political scene. All of that ultimately leads to the concentration of power outside official state institutions. Power dynamics in Libya are driven by armed militias and warlords, further complicating issues such as decentralization and national reconciliation. Questions regarding the role of Islam in legislation are less controversial, as conservative interpretations align with local values and traditions enjoy broad support across major political parties.