Public schools are going through tough times almost everywhere in Europe: the start of the new school year in September 2023 saw a series of major strikes in the UK, Wales, Ireland, Estonia, Lithuania, Portugal, Greece, Italy, Serbia, and even Germany, once considered a haven for education. If in the UK, school strikes for better pay and working conditions were partially addressed by the government’s promise to increase teachers’ pay by at least 6.5 percent in cash terms in the upcoming 2023/24 academic year, in Germany, consistent protests rocked what is usually considered one of the most rewarding environments for teachers in terms of wages and pay leave.

Germany’s Education Crisis: Dissatisfaction and Reform Urgency

The daily Hamburger Abendblatt went so far as to describe the protests as “one of the most serious education crises since the founding of the Federal Republic,” warning of a shortage of more than 12,000 teachers in the current year (but projected to rise to 25,000 by 2025). Germany’s 2023 Bildungsbarometer – a major survey periodically conducted on the state of education in the country – reports that 58 percent of respondents are unhappy with the school system (and that this number is rising, as it used to be only 45 percent in 2020), that 77 percent are concerned about the structural shortage of teachers, 66 percent lament underfunding, that 66 percent deplore a lack of innovation, 57 percent outdated facilities, and about 50 percent the lack of a good integration path for foreign- and second-generation children. Most respondents (79 percent) would like to see current teachers re-trained to fill current vacancies and relieved of administrative tasks to spend more time on education. In comparison, some 74 percent would like school authorities to take care of teachers’ mental health and 61 percent would rather import qualified teachers from abroad to fill existing gaps in the system.

Public opinion in Germany seems to be more polarized on the question of what would be an added value for schools in the 21st century, that is whether they should be more eager to meet the demands of their students (or their young clients in a neoliberal era), an option supported by 76 percent of the interviewed, or whether they should raise their teaching standards and conduct serious and thorough tests and examinations to prepare their students for a competitive labor market (a merit-based option supported by a fair 72 percent). However, the great majority of public opinion still sticks to the idea that education is an important public service that the states should not allow to crumble and fall, but whose setting needs a complete overhaul and would possibly benefit from a standardization of procedures between the different federal states to allow greater circulation of teachers and professionals at the national level, currently hindered by the diversity of recruitment procedures and career paths in the different states.

However, with some 3,007 private schools (12 percent of the schools) throughout Germany, the private sector is rapidly increasing its share in education, resulting in more attractive educational offerings, with tailor-made courses and innovative digital tools that better meet individual needs and expectations, particularly at the kita-level, i.e. is from the age of two on, where private schools seem to offer working parents more flexibility and guarantees than public schools. Nonetheless, the latest PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) results for 2023 show overall positive results for German students, who consistently score above the EU average in reading, mathematics, and science, but with a school system that promotes little social mobility and does little to address and reduce socioeconomic gaps between different youth groups (with an Academic Resilient Index of 113 points).

France’s Education Issues between Secular Values and School Segregation

In France, a country also plagued by major school strikes and protests at the beginning of the school year, President Macron personally took the stage to address the nation on the forthcoming educational reforms to be implemented following the July cabinet reshuffle under the second government of Élisabeth Borne and the appointment of a new Minister for Youth and Education, Gabriel Attal. Macron seems to be aware that some 64 percent of French citizens have a negative opinion of the quality of the school system – severely eroded over the last twenty years. A rate that brings the evaluation of public education close to that of other declining state services, such as hospitals and social services, and fuels the flames of public dissatisfaction with the government. Playing the education card to prove that his government could bring about change, the president promised a new school year marked by stricter observance of the rules on students’ clothing and duties to defend the core secular values at the heart of the Republic (the ban on abayas, the long and loose Islamic female garment that covers the whole body except the head, is a case in point). Also, it means setting among the government’s priorities the fight against bullying (after the suicide of a student last May) and the urgent need to raise the level of education, which has fallen sharply in recent years, placing France in 23rd place in the PISA ranking, causing a shock and a need to rectify the way basic subjects such as mathematics and reading are taught, and an increase in teachers’ salaries between 150 and 250 euros.

However, as noble as the government’s focus on education may be in its intention, its announced reform leaves out the “elephant in the room” and omits the great debate on the “Plan Mixité” introduced by the former minister Pap Ndiaye, who was willing to face the challenge of school segregation between the rich and the poor and between French-born and immigrant children, particularly sensitive when it comes to the 1449 private institutions in France, which are free by law to select their students according to their criteria.

In the new perspective sponsored by the Attal-Macron duo, there is no longer an urgent need to bring together different social constituencies, which are steadily growing apart in terms of educational and professional achievements, despite the tragic events of violent protests, looting, and social chaos that took place in the cities of Paris, Marseille, Lyon, Toulouse, and Bordeaux last summer following the death of a teenager, Nahel, a 17-year-old French-born citizen of Maghreb descent, in a popular neighborhood of Nanterre, close to the French capital’s financial district of La Defence.

The French researchers warn of a creeping “secession” of elites in private school systems that practice an alternative pedagogy (such as Montessori, Freinet, Steiner, or Decroly methods – which promise to raise eco-citizens (écocitoyens), active and enterprising children, better able to cope with a globalized and rapidly changing world. The Research Group on School Democratization (Groupe de recherche sur la démocratisation scolaire, GRDS) denounces the growing dual track of poor and rich students, where the latter are encouraged to experiment with new teaching methods and develop critical thinking, while the former are expected to achieve a basic understanding of standard core disciplines with little or no room for abstract subjects. In the end, students from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to be exposed to intellectual challenges, with the expectation that they won’t take on leading roles in society soon.

Italy’s Focus on Work-Study Balance Neglects School Dropout Concern

In Italy, the debate about school rages every year at the beginning of a new school year, particularly when a new government takes office and tries to set its agenda and spread its values through the education system. Since Renzi’s “Good School” reform in 2015, the public school system has been constantly striving to connect with the business world, implementing new programs to reconcile study and work experience – first called “Work-School Balance” and later “Cross-disciplinary Competences’ and Orienteering’s Path” (PCTO). Thanks to the funds of the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the Italian school system should undergo a thorough restructuring through six reforms and eleven investment plans outlined in the “Futura – Education for the Italian Future” scheme.

The €17.59 billion plan aims to create an “innovative, sustainable, safe and inclusive school system” capable not only of guaranteeing the universal right to education, as is currently the case, but also of equipping students with much-needed digital skills and fighting against the scourge of early school leaving and territorial gaps. The new school system believes in a meritocratic system based on the individual students’ needs and profiles, and bets on its ability to smooth the so-called education-to-employment challenge by introducing new professional services of orientation and tutoring to bridge the gap between an education system based mostly on theory and a practice-oriented labor market that requires a different set of skills. However, despite its flamboyant proclamations, the bulk of the investment in the school sector is channeled into the first pillar of intervention, which aims at the physical restructuring of the learning environments (about 100,000 classrooms) thanks to a forced injection of the latest technologies: customized computer devices, multifunctional screens, artificial intelligence, augmented reality, 3D printers, etc., and not enough funds nor attention are paid to other areas that also need urgent revision, such as school curricula and teaching objectives.

Moreover, little is made to address the long-standing problem of school dropouts, which puts Italy at a high risk of poverty and social exclusion among 0–17-year-olds (28 percent of the student population), compared to an EU average of 23 percent. In this sense, the recent communiqué of October 4, 2023, by the Minister of Public Education and Merit Valditara on the need to boost public-private partnerships for the renovation of buildings and to encourage project financing in schools by private investors and companies “to install solar panels to make schools energy self-sufficient institutions” is a wake-up call for the whole system, revealing the current government’s intention to further deepen school autonomy in management, financing and programs, thus exacerbating the different ability of schools to attracts funds depending on their territorial location and links to the business environment. Finally, there is not the slightest intention to increase regular funding of schools from the current 3.8 percent of GDP to the EU average of 4.6 percent, despite the lower PISA scores recorded in all three internationally tested skills (maths, science and reading).

Israel’s Exclusive Excellence Falters in Ensuring Equal Education Standards for All

If the picture of the state of education in Europe as a whole is bleak, Israel is considered the enfant prodige, known as one of the most educated countries in the world and considered a successful model, with its high-tech sectors recruiting from the best universities, but also from the country’s most innovative, technological and flagship high schools, betting their aces on success in technological entrepreneurship. The school system is considered the most innovative because it generally uses research-based methods, encouraging students to acquire knowledge by conducting scientific experiments rather than waiting for clear answers. In addition, alternative education is in vogue in the country, and new “democratic schools” – i.e. schools where organizational aspects are determined by the students themselves in assemblies, and where students are entitled to formulate their own rules of coexistence, plan activities, excursions, and conflict resolution, and enjoy total freedom to move around in different spaces and choose activities according to their interests –are quite popular. In addition, the educational system has differentiated tracks for average and gifted students, who are selected to pass qualifying tests and attend so-called “enrichment programs”, that is study programs where they independently research and study at their own pace.

However, not even Israel is heaven on earth, despite its progressive character and its outstanding results in technology: in fact, a report by the Shoresh Institution for Socioeconomic Research denounced that half of the population, consisting of Haredi students and Arab Israelis, who together make up 43 percent of all first graders, are left behind by the state and “receive a third-world level of education that is incapable of coping with a first world economy”. Indeed, Israel is a multicultural country and the school system reflects the social cleavages that exist in society, which is divided into four main groups: the secular Jews, both Ashkenazi and Mizrahim, who attend state schools (mamlachti); the national religious, who attend state religious schools (mamlachti dati); the ultra-Orthodox or haredim (khinuk ‘atzmai), who attend their own yeshivot or separate religious schools, and the Arabs and Druze, who attend their schools in Arabic. The four tracks follow different study programs, with the state schools devoting 8 hours per week to the study of the Bible, Hebrew language, and the history of Israel, the religious state schools devoting 13 hours to those subjects, the technological schools only 6 hours, the Haredi schools 14 hours with full exemption for the study of scientific subjects, and the Arab and Druze schools around 5 hours.

Overall, beyond Jewish religious identity, Israel lacks a core educational curriculum capable of fusing Arab, Jewish-secular, and Jewish-religious narratives of history and society into a distinctive but cohesive national identity. Nevertheless, the traditional balance between the majority secular Jewish group and the minority ultra-Orthodox religious groups is crumbling, tipping the scales in favor of the latter group, as the haredim are the main group behind Israel’s rapid population growth. The Shores report quotes that “the haredim’s share in the population – most of whom do not study core subjects and do not receive the basic tools to work in a competitive and global economy – is growing at a rate that is doubling their share in each generation.” A warning also echoed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in its recent “Going for Growth 2023” report, which called on Israel to stop subsidizing yeshiva students while increasing funding for Arab schools, in contrast to Finance Minister Smotrich’s self-proclaimed intention to increase budgets for ultra-Orthodox institutions slashing those for the Arab sector.

The latter measure is part of a general offensive by Smotrich to cut funding for Arab schools, including in East Jerusalem, and Arab local councils, in a tug-of-war with other ministries in his same government, to exacerbate an already tense climate. However, the country’s huge disparities in education levels among different groups and areas are pushing it to the edge of a cliff, with an ever-growing high-tech sector outpacing the rest of the economy, which lags far behind, a widening gender gap, and rising price levels, 38 percent higher than the OECD average. Israel is becoming a highly unequal country with some crown jewels in education and industry and a large mass of disadvantaged people living at second-class standards. It is foreseeable that educational innovation will reach new heights -as evidenced by the pilot project to install the “Imagine Box” device in some experimental schools to immerse students in a newly designed 3D education, which is expected to benefit 8,000 students spread over 20 schools in Gush Etzion is showing – but also that Arabs and Haredi Jews, the fastest growing sectors of the population, would hit rock bottom. It is questionable, though, how long a rich avant-garde would suffice to drag down the whole economy, particularly in the current strained situation revolving around the Justice Reform Bill, highly contested by the same high-tech sector.

In any case, public schools are almost universally facing adverse times, albeit with different shades and material conditions, threatened by multiple deficiencies: of resources, staff motivation, institutional credit, and of government backing. The general feeling is that their former mission, which stretches back to the 19th century and defines its goals according to the respective nation-state projects, is waning: public schools are no longer expected to educate the new citizens of tomorrow to build a community and be active within it, nor to shelter and enshrine democratic values of universal participation and solidarity, and are currently looking for a new mission. They are tossing and turning to find a new scope, but so far, they are just the main collateral victims of the crisis of liberal democratic politics and values in Europe (and in neighboring Mediterranean countries) and they won’t be able to reform themselves if the state authorities and public opinion do no come together to decide what kind of society they want to build in the next future.

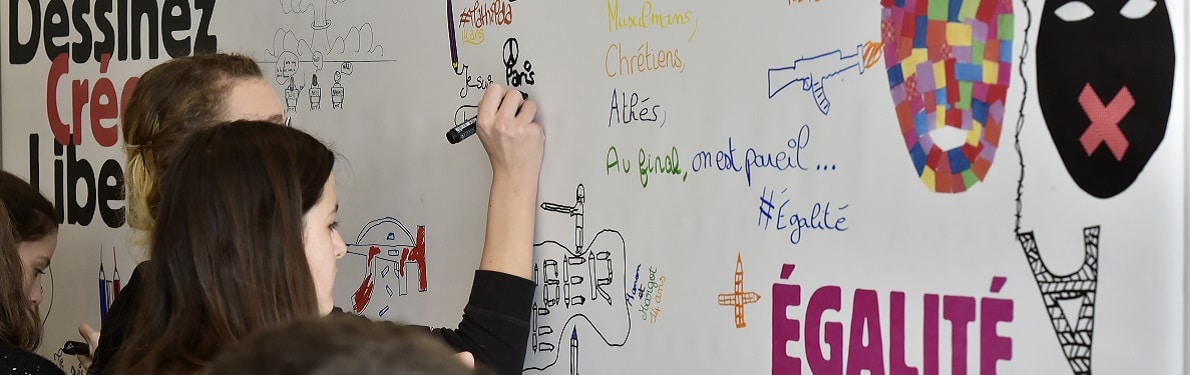

Cover photo: teenagers draw on January 29, 2016 in Angouleme, southwestern France on the sideline of the city’s Comics festival, during an educational action by the association “let’s draw, let’s create, liberty” supported by Charlie Hebdo, SOS Racisme and the Fidl high school association to support the freedom of expression. – Its first project is an exhibition of children drawings on the sideline of Angouleme Comics festival. (Photo by GEORGES GOBET / AFP.)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).