Pandora’s box has been opened, and evil has found fertile ground on Moroccan Internet: groups and pages with overtly racist content, xenophobic campaigns, and calls for boycotts targeting sub-Saharan migrants have filled social networks. “Moroccans against the settlement of sub-Saharans in Morocco,” “Moroccans against the marriage of Moroccan women with sub-Saharans,” “Moroccans against Afrocentrism,” “Defenders of the purity of the Moroccan race.” These are the names of some of the groups that in the space of a few months have garnered thousands of members and likes by taking the debate on racism and migrants beyond the virtual space.

To understand the resurgence of racism in a country that has deep African roots and whose young people, until just a few years ago were also among the victims of migrant routes in the Mediterranean, I infiltrated these groups and observed them for weeks to decipher their rhetoric and modus operandi. And as I waded into this xenophobic frenzy, I noticed that the phenomenon is far from being an exclusively Moroccan one.

The synchronism with which similar pages and groups have appeared simultaneously in all North African countries is curious. Hostility to migrants, at a time in history marked by high tensions between Maghreb countries, is doing what politics has failed to do: unite a cross section of Maghreb peoples. A Facebook group calling itself “The North African Union Against the Settlement of Sub-Saharans” is particularly active in haranguing its adherents, urging them to leave aside disagreements between Maghreb countries to unite against what is seen as a common enemy.

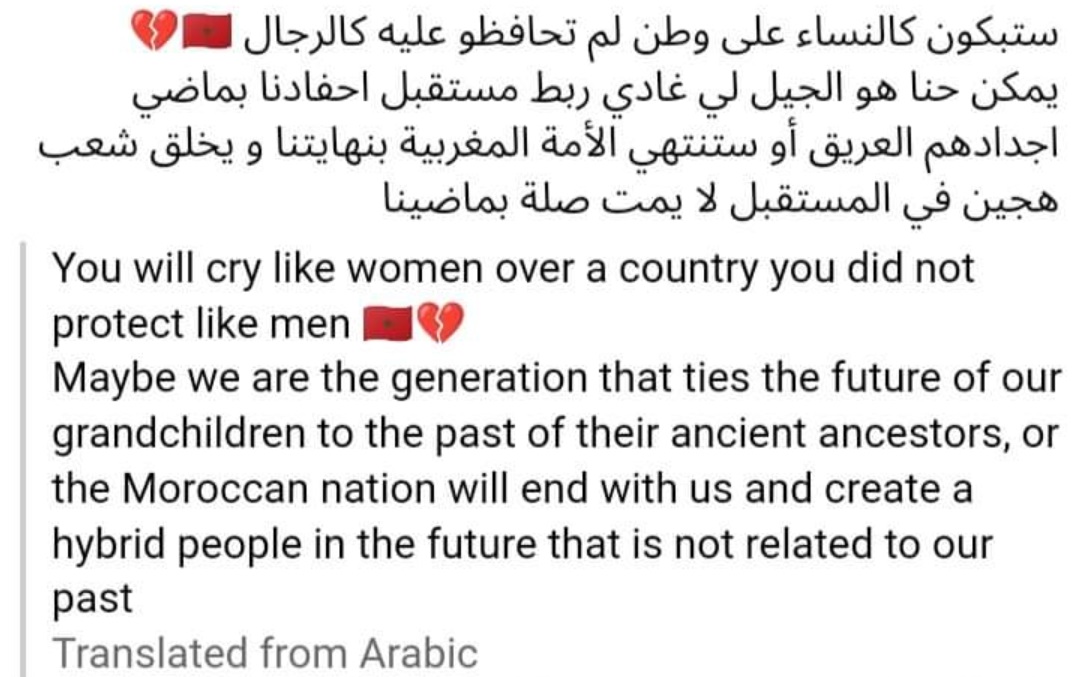

In a modus operandi that has all the aspects of a virtual guerrilla war, these groups swarm and as soon as the control systems of social platforms intercept and block one, others pop up. There are about twenty pages that call themselves “Moroccans Against the Settlement of Sub-Saharans,” and connected to them is a galaxy of other nationalist and populist groups and pages whose rhetoric closely resembles that of the European far right. The content posted by some is picked up by others and goes viral, creating a ripple effect that spreads the content widely.

Feeding the racist delusion is not only the migrant’s status as a foreigner belonging to a different cultural and ethnic group from the locals; the muckraking machine also targets skin color, religious faith and culture of origin. Some commentators accuse Sub-Saharans of being disease-ridden dog-eaters. The misdeeds of some are also emphasized and generalized to show that the “sub-Saharan” culture is intrinsically violent.

In this virtual bazaar of racism, fake news and conspiracy theories find ample space. According to Maghrebi conspiracists, an unspecified higher order has hatched an unholy design to subvert the demographics of North Africa in favor of sub-Saharans. In this view, migrants are nothing more than the outpost of an army of millions ready to march on North Africa to make it a black-majority zone. It is important to emphasize skin color, because in racist rhetoric this fact is central. Maghrebi racists present themselves as refractory to Afrocentrism, an old ethnocentric political ideology that militates for a black Africa and the supremacy of sub-Saharan values and cultures, and that in the last few months has come back into fashion and is used to give a veneer of veracity to the conspiracy theory of demographic subversion.

Let’s take a step back, in June 2015 some militants of a radical pan-African movement calling itself Unité, Dignité et Courage and inspired by the theories of Marcus Gravy – one of the leading theorists and leaders of Black nationalism – made headlines by conducting raids in Paris against a number of museums and diplomatic representations to protest the plundering of the African continent and denounce the conditions of migrants in the Maghreb.

The Moroccan embassy was one of the targets of this small group. Four militants managed to evade security and infiltrate the embassy shouting threatening slogans against Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia and calling on sub-Saharans to conquer North Africa. Their protest was filmed and spread on the movement’s social media. Eight years later, these videos along with other supremacist statements put online by the movement have been retrieved and again shared on pages of North African anti-immigration groups and gone viral, if not become a mainstay for their xenophobic rhetoric.

The fight against Afrocentrism has legitimized these heterogenous amalgams, an umbrella under which to hide to spew racist venom. The commentators and administrators of these social groups, who often hide under false avatars, exchange advice on strategies to adopt: some call for boycotting all those businesses that give work to sub-Saharans work, others insist that they must spread awareness about their dangerousness in public spaces, in schools and among families, and still others advise outwardly discriminating against them to make them understand that they are not welcome.

Most of these pages and groups were born between February and March 2023 shortly before or shortly after Tunisian President Kaïs Saïed’s incendiary statements against irregular migrants. Some pages that before this date dealt with completely different subjects seemed to jump into the fray either to catch more likes or out of a copycat effect. So much so that today the debate on reception and racism has moved out of the virtual space. The Moroccan government spokesman questioned by journalists about the spread of a racist culture on the web reacted by declaring that Morocco is a signatory to all international human rights conventions and that the Kingdom’s constitution and laws incriminate all forms of discrimination, calling on Moroccans to disassociate themselves from these minority voices.

Geographer Ali Bensaada, on the other hand, believes that manifestations of racism in the Maghreb are not new, and while it is true that in certain circumstances they become blatant, in truth they are rooted in the national identity constructions of Maghreb countries, based on an assumed ethnocultural homogeneity that perceives the different, even native, as a threat to the political, totalitarian and standardizing system**. Because of this, before the arrival of migrants it was black Moroccans or Amazighs who were often targeted. (The Amazigh, are the original inhabitants of the Maghreb, ethnically they are the majority group compared to the Arab minority. Their culture and language was for centuries the object of ridicule and marginalization until 2011 when it was institutionalized, alongside Arabic, as an official language of Morocco).

Now, in the presence of a new and yet more foreign minority, which is highly visible in the public space and willingly or unwillingly inciting gossip and talk, the mockery concerning skin color has shifted to them. To draw a parallel with Italy, the situations is similar somewhat to the southerners – or the so called “terroni” – before and after the arrival of immigrants. However, some affiliates of these groups take care to make a distinction between Moroccan blacks and sub-Saharan blacks and are keen to point out that the invitation made to women not to marry blacks should not be extended to Moroccan blacks because no matter how dark they are, they are still “less black” than Africans.

The question of mixed marriages was already a bee in racist bonnets. Last year, the daughter of a famous singer had married a Guinean national, and the sharing of their photos on social media provoked an uprising from many users who decried it as an attack against the purity of the Moroccan race. At the time, an online campaign was launched telling women not to marry sub-Saharans. No one could have imagined then that this would only be the prelude for the wave of virtual racism still underway.

To try to understand this phenomenon two Moroccan associations, the Ligue Marocaine pour la Défense des Droits Humains (Lmddh) and the Centre Marocain pour la Citoyenneté (Cmc), conducted a survey on racism in Morocco. Out of a sample of 3,158 people, 86 percent of respondents believe that the increase in migrants will be a serious problem for Morocco in the very near future, 66 percent oppose their permanent presence in the country, 72 percent reject that Morocco plays any role in countering irregular migration in favor of the European Union, and 87 percent believe that Casablanca should strengthen controls on its southern borders to prevent sub-Saharans from entering the country. The survey also revealed a very worrying finding: those expressing more radical hostility toward migrants are under the age of 30.

According to Lmddh President Adil Tchikitou the increase in virtual racism can be explained by a number of objective, subjective, and international reasons. First and foremost, is the economic and social crisis that Morocco is going through (rising prices, inflation, unemployment) that puts young people especially in a precarious situation. This has led many to develop the belief that the state favors migrants at the expense of locals and to see them as potential competitors for access to certain jobs. Moreover, migratory movements to Morocco have accelerated without any educational or pedagogical programs that lay any groundwork towards welcoming and accepting the other.

As for subjective considerations, according to Tchikitou, part of the responsibility with respect to the growth of racism would be the sub-Saharans themselves. The scenes of violent resistance toward the police during the eviction of some encampments or during the migrants’ attempts to cross the barriers separating Nador from Melilla, as well as the occupation of homes, are unusual attitudes for Moroccans that have aroused strong public outrage.

Finally, the international conjuncture marked by geopolitical instability has forced Morocco to face the burden of a phenomenon that should be managed with negotiated and agreed policies involving all the countries affected by the migratory surge, with the EU at the lead. In this regard, Tchikitou confided that in his opinion Morocco needs to renegotiate its migration agreements with the European Union and that he sees the latter’s inability to adopt a common policy as the biggest impediment to a humanizing approach to the migration phenomenon.

For me, however, humanity – the real kind – is found outside of virtual space. Within walking distance of my home is the Marché Dakar, since I have returned to live in Casablanca it has become a reference point for me, and it is there where I go to seek answers to the big question: Is Morocco a racist country?

Aided by my friend Fatimatou, a Senegalese who is part of the Association des Ressortissants Senegalais Residant au Maroc, I decide to ask the question directly to the Sub-Saharan diaspora. Fatimatou is an emblematic figure in Marché Dakar, her exuberance and optimism mirror that genuine sub-Saharan nature; she was among the first Senegalese to open a restaurant serving sub-Saharan dishes. I spend all afternoon with her; it’s Sunday, the market is packed.

I ask almost all of her patrons, and there are many. The vast majority of my interlocutors reply that racism exists everywhere in the world and that rather than listen to these voices, they prefer to focus on their own lives, looking after their children, working and building a future. I insist, asking if they have encountered difficulties finding housing, if they are taunted because of the color of their skin or their origins, and the vast majority of them insist that racists do not represent all Moroccans, that fools exist everywhere, and that they are a small minority in Morocco.

I talk to women, men, young and old, and the answers follow and resemble each other: there is no systematic racism against us. We are fine in Morocco. Moroccans also have problems with bureaucracy, inefficient services and unemployment. We are fine in Morocco. Morocco is not a racist country. I have been helped by many Moroccans. Racism exists all over the world.

After several hours spent logorrheically asking my question, Fatimatou begins to show some signs of impatience, somewhat amused and somewhat annoyed by the maieutic pressing of my questions, and invites me to take a walk outside the market. We walk near the medina, Fatimatou stops at every step to greet friends and acquaintances, Moroccan and sub-Saharan, and I continue to be absorbed in the hustle and bustle of the medina where hawkers, Moroccan and sub-Saharan, occupy the sidewalk with their stalls. Arabic is mixed with Wolof, French, and other languages I cannot distinguish. Fatimatou continues to wave, and I begin to think that in real life, racism, xenophobia, and skin color seem to be concerns as far removed from Moroccans as they are from sub-Saharans.

Cover Photo: an art installation, at the grounds of the International conference on Global Compact for Migration in the Moroccan city of Marrakech (photo by Fadel Senna / AFP.) All other pictures are taken by Rabii El Gamrani, all rights are reserved.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our stories, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month).