On December 4th, the Iranian regime announced that it had abolished its morality police, held responsible for Mahsa Amini’s death three months ago that sparked the current revolution. However, almost immediately, voices from inside Iran came out, debunking the disinformation. The loudest voices in cyberspace came from the Iranian Gen Z who has been the most vocal against the Iranian regime. From videos on TikTok of young students tearing pictures of Supreme Leader Khamenei, to short clips of teenagers knocking off clerics’ turbans, Iran’s Gen Z has found new and innovative ways to oppose the regime. However, this change did not just start with the revolution.

A @PBS Report: How #Iran’s Gen Z is leading protests in the streets and online against the #Hijab and the Islamic Republic. #IranRevolution #IranProtests https://t.co/7Ao089seN2 pic.twitter.com/4UiflwU1xk

— Tarek Fatah (@TarekFatah) October 3, 2022

As of 2022, more than 50 percent of Iran’s total 72 million people is under the age of 30. Gen Z consists of those born between 1997 and 2012, and is comprised of “digital natives”, who grew up with everyday access to technological devices, the Internet, and social media apps. Since the revolution in 1979, Supreme Leader Khamenei has repeatedly stated the importance of raising new generations with the strict and conservative values of the Islamic Republic. Even though the Iranian regime’s tactic was and is to use educational institutions, such as schools, to shape children as young as five to become followers of religious practices and enforce gender division already in primary schools, anonymous sources from inside the political élite have told media outlets that the Iranian regime concluded recently that it has failed to get the young people on their side.

One of the most impactful events for this conclusion can be traced back to the increased digital activities of the Iranian population within the last decade. Over 80 percent of the Iranian population has access to the internet and, prior to the current internet shutdowns, was able to access social media apps such as Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Therefore, especially young people used social media apps as a tool to communicate with the outside world, which influenced their way of seeing the world outside of Iran. To offer a personal instance, one of my friends in Tehran sent me in the beginning of the year a video of her 25th birthday party. There were men and women in the background, dancing together to Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda” and Stromae’s “Alors on Danse”. Contrary to reports of some popular Western media outlets, Iran’s Gen Z can be defined as a globalized generation with great level of awareness about events happening outside of Iran.

Within the Iranian regime, social media is marked by a lack of a coherent strategy. No official statements regarding the actual impact social media has had on the younger Iranian generations have yet to be published. The only mention by Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei on the issue came in a Friday prayer in 2020, where he described social media as being “evil axes of the West”. Therefore, most Iranian officials underestimated the great emotional impact of “feeling free” in the digital cyberspace has had on its young generation.

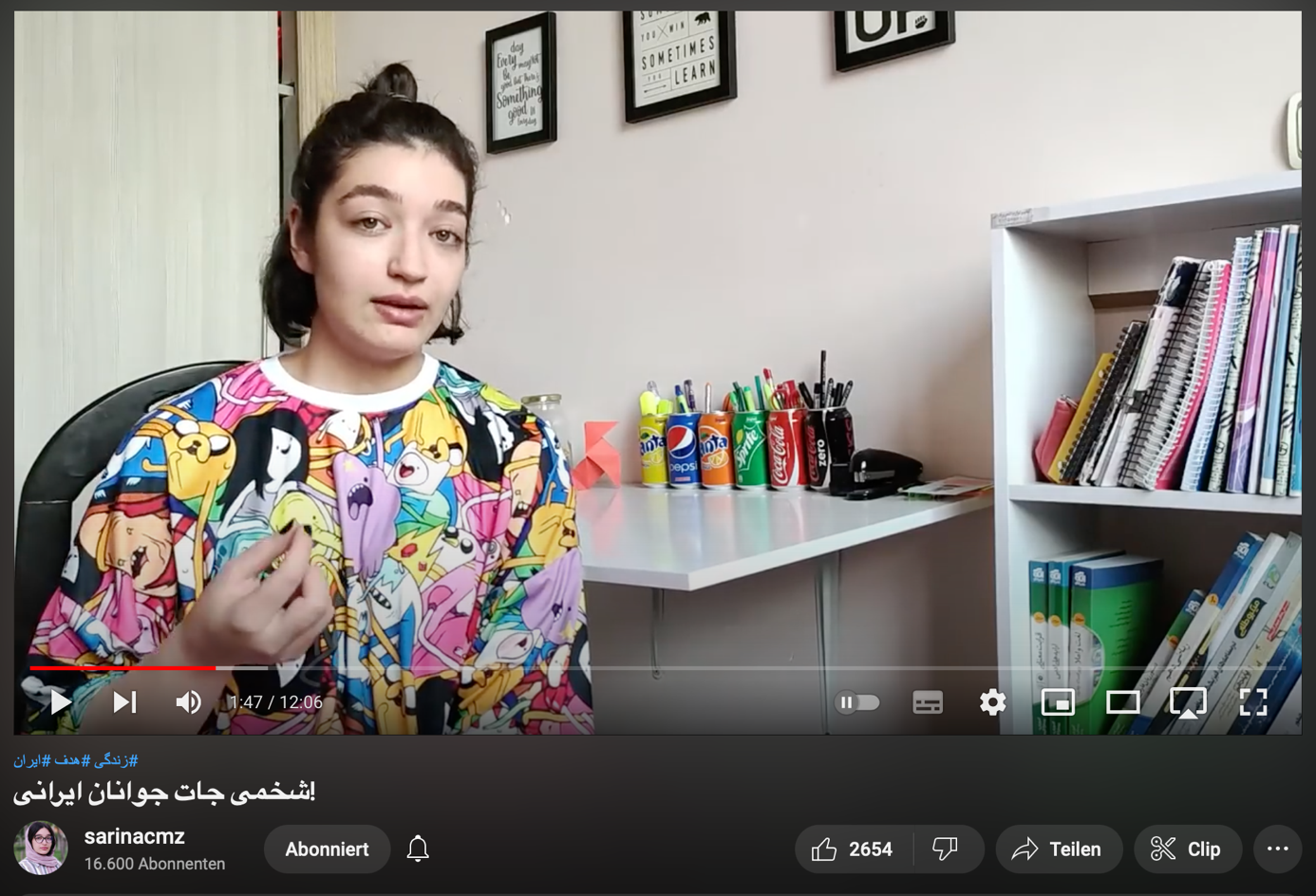

Tragic examples are found with the victims of the current revolution. Sarina Esmailzadeh, 16, who was shot in the first weeks of the protests in September 2022, had a YouTube channel where she would frequently upload videos about her life as a student in Iran. In one video, she stalks about the future of young Iranians in their country stating, “We want to be free like the kids in the US, we want to be able to have a future”.

Another example is the case of Hadis Najafi, a 20-year-old woman who got shot in the second week of the protests by Iranian police and died later in the hospital. Hadis was a “TikToker”. She had an active account on TikTok, where she would regularly post videos of her dancing and singing to Iranian as well as contemporary Western songs. Without knowing her location, one could have guessed that she was just another student from a big, Western metropole, living her life. This makes her last video, a message to her family, even more heartbreaking. Hadis is seen alone on her way to a protest, she is putting her scarf around her mouth and says that she wants to be able to say in the future that she was on the streets as well, fighting for a free and equal Iran.

#حدیث_نجفی در آخرین پیامی که قبل از رفتن به اعتراضها (چهارشنبه ۳۰ شهریور) برای دوستانش فرستاد، میگوید:

«خیلی دوست دارم الان که دارم میرم آخرش وقتی چند سال گذشت خوشحال باشم رفتم تظاهرات و همه چی عوض شده…»#مهسا_امینی #Mahsa_Amini pic.twitter.com/oORoUyTpNW— Farzad Seifikaran (@FSeifikaran) September 26, 2022

The digital footprint left by the over 40 underaged victims killed by the Iranian regime is perhaps most emblematic in the case of 10-year-old Kian Pirfalak. Kian was shot on November 16th, while sitting on a bench with his father in Izeh, in the Khuzestan province of Iran. Immediately after his death, videos of him dancing with his family, playing with his friends, and showing his models of little boats, were being shared all over social media. In one video, he recites a poem by Mahmoud Pourohab called In the name of God of the rainbows, which is common in 3rd grade school books. The days following his death, more school children shared drawings they made with little rainbows on them on social media, showing opposition to the Islamic Republic by remembering Kian.

Within the last few years, the Iranian regime started to slowly grasp the dangers of cyberspace for the regime’s political legitimacy. A few months prior to the revolution, a bill was passed in parliament that declared full state control over the Internet and cyberspace, with the goal of restricting further expansion and use of Western social media applications by Iran’s Gen Z. The gap in digital literacy between Iran’s Gen Z and the political élite can therefore be seen as one of the main pillars and reasons for the disconnect between the young and old generations.

A second pillar further reinforcing the gap are the strong ideological differences between the generations. Whereas Iran’s political, military, and institutional branches work under the Iranian regimes interpretation of Sharia Law and follow strict conservative rules (e.g., modesty, daily prayers, strict gender division) the younger generation has its own way of seeing the world.

Interestingly, Iran’s Gen Z does not follow a particular ideology. Their dreams are pragmatic, demanding a free country, a just and equal society, and financial stability. The generation of the 1979 revolution was marked by different ideologies who all had their own ideas for a new Iran. Marxists, Communists, student groups, and Islamists fought side by side against the monarchy of Shah Reza Pahlavi. However, in the current revolution, there is no particular ideology to be found, with Gen Z simply demanding freedom and equality. With a literacy rate of over 90 percent, but an unemployment rate of over 40 percent amongst Gen Z and Millennials – born between 1981 and 1996 – the younger generations are frustrated by the promises that the Iranian regime has made in the past. While growing up, they have witnessed corruption, economic mismanagement, and repression of diverging opinions. Financial stability and, as Sarina put it in her video, social welfare, are simple but powerful demands with regards to the current deterioration of Iran’s social, economic, and environmental infrastructure.

The response of the Iranian regime to these demands of Iran’s Gen Z further reflects the former’s lack of understanding regarding younger generations. In October 2022, officials of the Iranian regime described the Gen Z protestors as “immature” and “spoiled,” with many of the young protestors being forcibly sent to mental health facilities. The goal of the Iranian regime is to “reform” their “anti-social” behaviors. The commander of the Revolutionary Guard, Ali Fadavi made fun of captured protesters, stating that young Iranians see the protests too much as a video game. Education Minister Yousef Nouri stated that security forces will interrogate young protesters in these facilities and if necessary, even with force.

Gen Z’s growing frustration about the Iranian regime’s response to the protest as well as seeing fellow protestors getting arrested, tortured, and killed, has led to a new phenomenon, satirically dubbed “Turban-Tossing”. Young Iranians are filming each other as they run by Shia clerics and knock off their turbans, symbols of their high status within the clerical structure. Even though not every cleric is automatically a supporter of the regime, they represent an unwanted image of those in the top positions. Interestingly, Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran’s first Supreme Leader following the 1979 Revolution had demanded in one of his Friday speeches in early 1979, that every protestor should knock the turbans off the heads of those clerics, that were not on the side of the revolutionaries. Young Iranians are fully aware of the irony of this statement and further fuels feelings of anger and frustration against the current regime.

As the protests in Iran continue, there's a trend of clerical "turban throwing" #عمامه_پرانی

Iranians are uploading videos of themselves knocking off or stealing a cleric's turban and (usually) running away.

(Song is Toomaj Salehi’s "Rathole")#MahsaAmini pic.twitter.com/hCN3fnZGKH

— Holly Dagres (@hdagres) November 7, 2022

This new trend may sound like a “fun” way of opposing the regime, yet 16-year-old Arshia Emamgolizadeh was jailed for ten days after tossing a clerics turban. After his release, his family reported that Arshia had endured harsh mental and physical torture inflicted by Iran’s security personnel during his imprisonment. He committed suicide 5 days later.

Other young women who had active social media accounts and either participated in protests or publicly stated their solidarity have been arrested within the past weeks. 19-year-old Yalda Aghafazli got arrested for 12 days after protesting in the streets. A week after her release, she committed suicide due to the consequences of what she had endured. Other young women, such as 20-year-old Armita Abassi, with active social media profiles, are still missing and are at great risk of mental, physical, and sexual torture. Armita was an outspoken supporter of the protests and shared supportive messages under her real name.

It is the decades-long neglect of the demands of the younger generations, the ignorance around the realities of the cyberspace, corruption, and mismanagement of the Iranian economy that have led to young people in particular to pour into the streets and protest for their rights. As two teenage Iranian influencers state in a TikTok video, they are ready to die for this fight, proceeding with saying their goodbyes, hoping one day to once again be able to produce content after the revolution is achieved.. One can only hope that the Iranian regime will begin to grasp their distance from this young and brave generation that will not stop the fight for “Woman, Life, Freedom”.

Cover Photo: A woman with false tears of blood and the Iranian flag on her cheek waves the Iranian flag near a drawing of Mahsa Amini. Iranians of Toulouse organized a protest in Toulouse in solidarity with women and protesters in Iran. France. December 3rd 2022 (Photo by Alain Pitton/NurPhoto via AFP.)

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn to see and interact with our latest contents.

If you like our analyses, events, publications and dossiers, sign up for our newsletter (twice a month) and consider supporting our work.