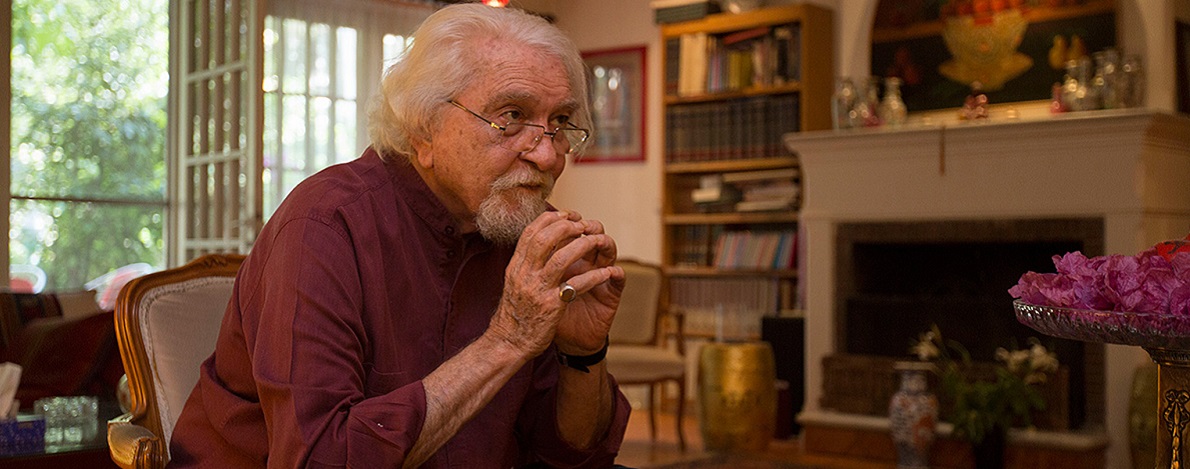

Sitting in his living room decorated with Buddha heads, a Shiva statue and several Tibetan thangka paintings, he reiterated his consistently held belief that younger Iranians – who constitute a majority of the population – had moved beyond the Islamic revolution principles. However, in the short term, he is not optimistic that Iran will have an easy time – both due to the prevailing hostility in the region, as well as, domestically.

Rouhani won 57% of the votes on a reformist platform, which was based on a call for outreach to the world and greater social openness. Towards the end of the campaign, he also pivoted towards sharp attacks on the security and clerical establishment.

Shayegan is a strong proponent not just of talks with the US, but also of “proper” diplomatic ties with Washington, which he believes is absolutely essential to really get the full benefit from Iran’s outreach to the world.

Having been educated in Persia, England, Switzerland and France, Shayegan, who has straddled both East and West, is known for his writings on comparative religion and philosophy stretching from Europe to Iran and India. He was a professor of Indian studies and comparative philosophy at Tehran University from 1962 to 1980.

Having studied Sanskrit, he wrote two volumes in Persian on the religions and philosophies in India. Armed with a doctorate on Dara Shikoh, he also wrote a book on the 17th-century Mughal prince’s treatise, Majma-ul-Bahrain (Mingling of the Oceans).

In 1976, he founded the Iranian Centre for the Study of Civilizations at Tehran University, which was sponsored by Queen Farah. A year later, the centre organised an international symposium which advocated inter-civilisational dialogue. Two decades later, the idea was picked up by Mohammad Khatami after his election as the Iranian president as the ‘Dialogue for Civilisations’. In 2009, he was the first recipient of the Global Dialogues award.

After the Islamic revolution, Shayegan went on a self-exile to Paris, where he stayed for a quarter of a century. He wrote over 100 publications, but one of his best-known books was on ‘Cultural Schizophrenia’, which was a pioneering work on the encounters of Islamic societies with modernity. Currently, he has retired academically but remains one of Iran’s best-known intellectuals.

A day after the presidential election results were announced, he spoke about the direction of the Islamic republic, the failure of the Islamic revolution and the rise of Hindutva in India.

The interview has been edited for clarity.

Excerpts:

You had said that there was a cycle where first Islam enters politics and then there is an inevitable move towards secularisation of politics. Do you believe that win of reformists in this presidential election are part of the cycle of secularisation of the Iranian politics and polity?

This has been going on for 37-38 years since the Islamic revolution. But Iran remains an Islamic republic. It cannot change its fundamental values. We can hope that we can modify certain things. But the problem is that as long as you haven’t opened up to other countries, especially if you don’t have political relations with the United States and all other countries, then you don’t have capital investment in this country, and then the economy will not grow. It is as simple as that.

That’s the whole problem with Iran. Since the revolution, Iran has always taken a stance against the West – and that’s what they called fundamentalism.

You have also articulated several times that young Iranians are no longer moored to these Islamic republic principles.

The generation after revolution lives in a post-Islamic world – mentally at least. The only social category that resisted very much the revolution are the women. They have done a fantastic job. They have not been able to control the women.

Why is that?

In that case, Iran is unique. if you travel through other Islamic countries, you see that there is a process of re-Islamisation. Look at Turkey, North Africa, even at continental Africa…

Indonesia.

Indonesia. (Nods)

All these countries in Southeast Asia in the old days were either under the influence of Indian civilisation or Chinese civilisation. I have been to Cambodia and Vietnam. Cambodia is nearly Hindu, Vietnam is more Chinese. So there are two main civilisation in the Far East, which have influenced all the others. India has played in Asia the same role as Greece in the West. It is amazing the impact that it has had.

And of course, our relations with India has been very close, because in the very old days, we probably lived together. We don’t know when, but there was an Indo-Iranian society some 3000-4000 years ago and then they separated. Some of them went to the Indian subcontinent, the other went to the Iranian plateau. When you looks at the old books, Avesta, Vedas, they are almost like sister languages.

Where do you place or view the rise of Donald Trump in America?

The lunatic in United States called Mr Trump, who is an egomaniac, schizophrenic, whatever you may call him. Narcissistic fellow. They are already talking about impeachment. I think that it will happen somehow. I don’t think he will finish his term. That’s my opinion.

Since he is surrounded by Iran hawks, whatever Trump does or says would certainly impact Iran’s external environment negatively.

Of course, it affects Iran. It will affect the rest of the world. He said that NATO is obsolete and also wants to talk about peace between Israelis and Palestine. Many of his predecessors were more intelligent than he was and did not succeed.

The Saudis are very much against Iran and are trying to give him a royal reception.

We live in a dangerous world because America is important. The only superpower we have. Then you have Putin who is a remarkable chess player. He wants to reconstitute the Russian empire if he can. There are plenty of madmen all over the world.

Do you think that the hostility from White House could derail Rouhani’s manifesto of opening to the world – in the sense, that sabre-rattling in Washington could strengthen the hands of conservatives in Iran?

I know that he (President Rouhani) wants to make changes. But, in my opinion, as long as he doesn’t have proper diplomatic relations with the United States, nothing would work. The European banks won’t come and invest because they have so much interest in the United States – which they won’t sacrifice in order to benefit us.

Besides, Iran is playing a big role in Syria and Lebanon. Also now in Yemen – I don’t know whether it is true or not.

There was a mullah who said something very funny. He said, “We haven’t come to mend this economic situation so that the country becomes more prosperous. If we were supposed to do that, then the Shah was much better than us. We brought Islam. That was our only aim and fight the superpowers in the world.”

After all these years, who are Iranians more aligned to – Islam, the religion or Iran, as the national culture?

Iranians are very proud people. We had three big empires – Achaemenid empire, Parthian empire and the Sassanid empire. All of them add up to one thousand and four hundred years. These were huge empires which extended from India, up to Europe and Egypt and northern Africa. That reflects in Iranians in their subconscious mind. There is that pride that they have been important one day.

And with regard to Islam, all the great Islamic philosophers are of Iranian origin. I am not trying to be a chauvinist. Look at Avicenna, Al-Farabi, Ghazali, Suhrawardī. All these guys were Iranians.

Of course, there is Shi’ism and Sunnism, with their differences.

Even in Shi’ism, there are two pillars which come from all Iranian beliefs. One of them is the idea of saviour, like in Buddhism, you have the idea of Maitreya, future Buddha. In Zoroastrianism, they call it the Saoshyant, the future Zoroaster. It became in Islam, the Mahdi, the 12th imam.

The other idea is the idea of dynasty, because all the imams are together part of a dynastic structure. These two ideas are Iranians. That’s why Iranians easily adopted Shi’ism. According to Sunnis, we are heretics of course. That’s how it is.

If young Iranians are living in a post-Islamic society, as you said, do they identify themselves mainly as Iranians?

Oh yes, it is amazing. People go to Pasargadae, which is the tomb of Cyrus the great (founder of Achaemenid empire) and celebrate his birthday. Thousands of people go there.

These people have saturated the mind of the people with Islam so much that it has created a reaction. I am not saying that they are rejecting Islam. I am saying that they are fed up.

Where do you see this process leading up to?

In the long term, I am very optimistic about Iran. In the short term, we will have plenty of ups and downs.

What the Westerners don’t know is that before the revolution, Iran was on the verge of becoming a real Asian power. We started our auto industry much before South Korea. I remember, we had South Korean workers in Iran. For 20 years we had 11% growth.

So when you see what happened, what we were and what we became, we were supposed to be South Korea and ended up becoming North Korea.

But any visitor to this Iran is also rather impressed with the visible infrastructure development and vibrancy on the streets.

Yes, because the society here is a very living society.

And people are relatively free to talk?

Yes, like me. I told you things that I shouldn’t have said. But nevertheless, on the whole, this revolution was a failure. At all levels. Like all the revolutions. If you take the pattern of the French revolution, which repeated itself in Soviet Russia, China, it is always a failure.

The ideas of Islam and revolution are antithetical. Revolution is a modern idea which was introduced at the end of 18th century in France and which had revolutionary social impact.

But, if you look at the Quran, you won’t find even a word for it. The concept did not exist, neither in Iran, nor in India, nor in china.

You said that in the short term, Iran could go through ups and downs. What are the danger points for Iran?

I wrote a book in French many years ago called What’s a Religious Revolution. I wrote that when a religion falls into the trap of revolution, it becomes an ideology. It was called the process of ideologisation of religion and when the religion becomes an ideology, then it becomes like all ideologies – it loses its transcendent dimension.

Do you see any application of your theory in India?

Hindutva is like this. It never existed in India, you know. It is so new, for me, this idea. I think that you have been contaminated by Islamic radicalism. I said to a Hindu friend that you’ve been semitised like us.

Why do you think that Hindutva has evolved in India?

If you look back into Indian history 3000-4000 years ago, what has always characterised India has been its tolerance. In fact, Hinduism has been a big stomach as it has digested everything.

Who could imagine that in 6th century BC, a person from the Kshatriya caste would come and would negate the authority of the Vedas and the equation of atman and brahman and vedanta and bring a new religion and will not be considered as a heretic. Imagine that this had happened in Judaism, Christianity or Islam. Immediately, he would have been killed. I am referring to the Buddha, of course. That always amazed me to see that how is that this fundamentalism is such contagious malady that is contaminating everything, including Hinduism.

When you study Indian thought, you’ll never see such… because first of all there is not one God. Of course, behind all that there is a Brahman, but it is polytheism, almost democratic. But a single God is always a very jealous God, because he wants only for himself.

So this is a new idea, and I don’t understand it. It’s very anti-Hindu, in my opinion.

Hindutva’s origins are traced to British Raj and [Vinayak Damodar] Savarkar’s writings.

Maybe, maybe it was a colonial thing.. the British, they always ruled by dividing, that’s what they did all the time… But whenever I went to India, I didn’t feel any resentment against the British, because the Indians say we learned very much from them, which is true in a way.

I think it’s an over-reaction to what happened in Iran 40 years ago. I think the Iranian revolution had an immense impact all over the world. Look, after the Iranian revolution the Russians invaded Afghanistan, the Americans started helping the Mujahideen, then you have al-Qaida, then you have the Taliban, right? And then Americans invaded Iraq which was a stupid thing to do. And afterward they couldn’t manage it and now they go after the Daesh. So you see there was a chain of events which followed each other automatically. But the whole idea of an Islamic radicalism started with the Iranian revolution.

Have you been to India recently?

Two years ago I went to visit friends and I stayed for two weeks. But, India is changing a lot. I first saw India in 1964, when Nehru was still alive. I met him at the Orientalism Congress. I was very young and it was another India.

How has India changed?

There are too many nouveau riche people, that’s the problem you have. We have the same problem here in Iran.

Are you following what is happening in India right now?

Not quite. Of course, radical Islam is something that everybody is fighting…and you are lucky that you had partition anyway.

In Delhi recently, authorities recently renamed a road in Delhi – Aurangzeb road – after former Indian president APJ Abdul Kalam. And they renamed another road Dalhousie road to Dara Shikoh road. How do you perceive this development, which in some Indian quarters was seen as a political move too.

I think they are exploiting him in a way. They should use Dara Shikoh as a symbol of tolerance, not as a nationalistic figure.

I was amazed to see under the Mughals (they were very intelligent people) 60 Hindu Sanskrit texts were translated into Persian. Bhagavat Gita was translated, the Mahabharata was translated, the Ramayana was translated, the Yoga sutras were translated. Dara Shikoh himself translated 50 Upanishads into very fluent Persian.

He was the governor of Benares. What Dara Shikoh wants to say is that he wanted to bring a common ground so that Hindus and Muslims could live peacefully together. That’s why Akbar married a Hindu wife. These people were very intelligent, but this all changed with Aurangzeb.

Had he succeeded, you won’t have that partition that you had. Aurangzeb had the nerve to build a mosque in Benares… I mean, can you imagine building a mosque in Vatican? It’s as stupid as that you know.

This article written by Devirupa Mitra was published on The Wire on 29 May 2017